sentimentr is designed to quickly calculate text polarity sentiment at the sentence level and optionally aggregate by rows or grouping variable(s).

sentimentr is a response to my own needs with sentiment detection that were not addressed by the current R tools. My own polarity function in the qdap package is slower on larger data sets. It is a dictionary lookup approach that tries to incorporate weighting for valence shifters (negation and amplifiers/deamplifiers). Matthew Jockers created the syuzhet package that utilizes dictionary lookups for the Bing, NRC, and Afinn methods as well as a custom dictionary. He also utilizes a wrapper for the Stanford coreNLP which uses much more sophisticated analysis. Jocker’s dictionary methods are fast but are more prone to error in the case of valence shifters. Jocker’s addressed these critiques explaining that the method is good with regard to analyzing general sentiment in a piece of literature. He points to the accuracy of the Stanford detection as well. In my own work I need better accuracy than a simple dictionary lookup; something that considers valence shifters yet optimizes speed which the Stanford’s parser does not. This leads to a trade off of speed vs. accuracy. Simply, sentimentr attempts to balance accuracy and speed.

So what does sentimentr do that other packages don’t and why does it matter?

sentimentr attempts to take into account valence shifters (i.e., negators, amplifiers (intensifiers), de-amplifiers (downtoners), and adversative conjunctions) while maintaining speed. Simply put, sentimentr is an augmented dictionary lookup. The next questions address why it matters.

So what are these valence shifters?

A negator flips the sign of a polarized word (e.g., “I do not like it.”). See

lexicon::hash_valence_shifters[y==1]for examples. An amplifier (intensifier) increases the impact of a polarized word (e.g., “I really like it.”). Seelexicon::hash_valence_shifters[y==2]for examples. A de-amplifier (downtoner) reduces the impact of a polarized word (e.g., “I hardly like it.”). Seelexicon::hash_valence_shifters[y==3]for examples. An adversative conjunction overrules the previous clause containing a polarized word (e.g., “I like it but it’s not worth it.”). Seelexicon::hash_valence_shifters[y==4]for examples.

Do valence shifters really matter?

Well valence shifters affect the polarized words. In the case of negators and adversative conjunctions the entire sentiment of the clause may be reversed or overruled. So if valence shifters occur fairly frequently a simple dictionary lookup may not be modeling the sentiment appropriately. You may be wondering how frequently these valence shifters co-occur with polarized words, potentially changing, or even reversing and overruling the clause’s sentiment. The table below shows the rate of sentence level co-occurrence of valence shifters with polarized words across a few types of texts.

| Text | Negator | Amplifier | Deamplifier | Adversative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannon reviews | 21% | 23% | 8% | 12% |

| 2012 presidential debate | 23% | 18% | 1% | 11% |

| Trump speeches | 12% | 14% | 3% | 10% |

| Trump tweets | 19% | 18% | 4% | 4% |

| Dylan songs | 4% | 10% | 0% | 4% |

| Austen books | 21% | 18% | 6% | 11% |

| Hamlet | 26% | 17% | 2% | 16% |

Indeed negators appear ~20% of the time a polarized word appears in a sentence. Conversely, adversative conjunctions appear with polarized words ~10% of the time. Not accounting for the valence shifters could significantly impact the modeling of the text sentiment.

The script to replicate the frequency analysis, shown in the table above, can be accessed via:

val_shift_freq <- system.file("the_case_for_sentimentr/valence_shifter_cooccurrence_rate.R", package = "sentimentr")

file.copy(val_shift_freq, getwd())There are two main functions (top 2 in table below) in sentimentr with several helper functions summarized in the table below:

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

sentiment

|

Sentiment at the sentence level |

sentiment_by

|

Aggregated sentiment by group(s) |

profanity

|

Profanity at the sentence level |

profanity_by

|

Aggregated profanity by group(s) |

emotion

|

Emotion at the sentence level |

emotion_by

|

Aggregated emotion by group(s) |

uncombine

|

Extract sentence level sentiment from sentiment_by

|

get_sentences

|

Regex based string to sentence parser (or get sentences from sentiment/sentiment_by)

|

replace_emoji

|

repalcement |

replace_emoticon

|

Replace emoticons with word equivalent |

replace_grade

|

Replace grades (e.g., “A+”) with word equivalent |

replace_internet_slang

|

replacment |

replace_rating

|

Replace ratings (e.g., “10 out of 10”, “3 stars”) with word equivalent |

as_key

|

Coerce a data.frame lexicon to a polarity hash key

|

is_key

|

Check if an object is a hash key |

update_key

|

Add/remove terms to/from a hash key |

highlight

|

Highlight positive/negative sentences as an HTML document |

general_rescale

|

Generalized rescaling function to rescale sentiment scoring |

sentiment_attribute

|

Extract the sentiment based attributes from a text |

validate_sentiment

|

Validate sentiment score sign against known results |

The equation below describes the augmented dictionary method of sentimentr that may give better results than a simple lookup dictionary approach that does not consider valence shifters. The equation used by the algorithm to assign value to polarity of each sentence fist utilizes a sentiment dictionary (e.g., Jockers, (2017)) to tag polarized words. Each paragraph (pi = {s1, s2, …, sn}) composed of sentences, is broken into element sentences (si, j = {w1, w2, …, wn}) where w are the words within sentences. Each sentence (sj) is broken into a an ordered bag of words. Punctuation is removed with the exception of pause punctuations (commas, colons, semicolons) which are considered a word within the sentence. I will denote pause words as *c**w* (comma words) for convenience. We can represent these words as an i,j,k notation as wi, j, k. For example w3, 2, 5 would be the fifth word of the second sentence of the third paragraph. While I use the term paragraph this merely represent a complete turn of talk. For example it may be a cell level response in a questionnaire composed of sentences.

The words in each sentence (wi, j, k) are searched and compared to a dictionary of polarized words (e.g., a combined and augmented version of Jocker’s (2017) [originally exported by the syuzhet package] & Rinker’s augmented Hu & Liu (2004) dictionaries in the lexicon package). Positive (wi, j, k+) and negative (wi, j, k−) words are tagged with a +1 and −1 respectively (or other positive/negative weighting if the user provides the sentiment dictionary). I will denote polarized words as *p**w* for convenience. These will form a polar cluster (ci, j, l) which is a subset of the a sentence (ci, j, l ⊆ si, j).

The polarized context cluster (ci, j, l) of words is pulled from around the polarized word (pw) and defaults to 4 words before and two words after pw to be considered as valence shifters. The cluster can be represented as (ci, j, l = {pwi, j, k − nb, …, pwi, j, k, …, pwi, j, k − na}), where nb & *n**a* are the parameters n.before and n.after set by the user. The words in this polarized context cluster are tagged as neutral (wi, j, k0), negator (wi, j, kn), amplifier [intensifier] (wi, j, ka), or de-amplifier [downtoner] (wi, j, kd). Neutral words hold no value in the equation but do affect word count (n). Each polarized word is then weighted (w) based on the weights from the polarity_dt argument and then further weighted by the function and number of the valence shifters directly surrounding the positive or negative word (pw). Pause (cw) locations (punctuation that denotes a pause including commas, colons, and semicolons) are indexed and considered in calculating the upper and lower bounds in the polarized context cluster. This is because these marks indicate a change in thought and words prior are not necessarily connected with words after these punctuation marks. The lower bound of the polarized context cluster is constrained to max{pwi, j, k − nb, 1, max{cwi, j, k < pwi, j, k}} and the upper bound is constrained to min{pwi, j, k + na, wi, jn, min{cwi, j, k > pwi, j, k}} where wi, jn is the number of words in the sentence.

The core value in the cluster, the polarized word is acted upon by valence shifters. Amplifiers increase the polarity by 1.8 (.8 is the default weight (z)). Amplifiers (wi, j, ka) become de-amplifiers if the context cluster contains an odd number of negators (wi, j, kn). De-amplifiers work to decrease the polarity. Negation (wi, j, kn) acts on amplifiers/de-amplifiers as discussed but also flip the sign of the polarized word. Negation is determined by raising −1 to the power of the number of negators (wi, j, kn) plus 2. Simply, this is a result of a belief that two negatives equal a positive, 3 negatives a negative, and so on.

The adversative conjunctions (i.e., ‘but’, ‘however’, and ‘although’) also weight the context cluster. An adversative conjunction before the polarized word (wadversative conjunction, …, wi, j, kp) up-weights the cluster by 1 + z2 * {|wadversative conjunction|,…,wi, j, kp} (.85 is the default weight (z2) where |wadversative conjunction| are the number of adversative conjunctions before the polarized word). An adversative conjunction after the polarized word down-weights the cluster by 1 + {wi, j, kp, …, |wadversative conjunction|* − 1}*z2. This corresponds to the belief that an adversative conjunction makes the next clause of greater values while lowering the value placed on the prior clause.

The researcher may provide a weight (z) to be utilized with amplifiers/de-amplifiers (default is .8; de-amplifier weight is constrained to −1 lower bound). Last, these weighted context clusters (ci, j, l) are summed (c′i, j) and divided by the square root of the word count (√wi, *j**n) yielding an unbounded polarity score (δi, j*) for each sentence.

δij = c’ij/√wijn

Where:

c′i, j = ∑((1 + wamp + wdeamp)⋅wi, j, kp(−1)2 + wneg)

wamp = ∑(wneg ⋅ (z ⋅ wi, j, ka))

wdeamp = max(wdeamp′, −1)

wdeamp′ = ∑(z(−wneg ⋅ wi, j, ka + wi, j, kd))

wb = 1 + z2 * wb′

wb′ = ∑(|wadversative conjunction|,…,wi, j, kp, wi, j, kp, …, |wadversative conjunction|* − 1)

wneg = (∑wi, j, kn ) mod 2

To get the mean of all sentences (si, j) within a paragraph/turn of talk (pi) simply take the average sentiment score pi, δi, j = 1/n ⋅ ∑ δi, j or use an available weighted average (the default average_weighted_mixed_sentiment which upweights the negative values in a vector while also downweighting the zeros in a vector or average_downweighted_zero which simply downweights the zero polarity scores).

To download the development version of sentimentr:

Download the zip ball or tar ball, decompress and run R CMD INSTALL on it, or use the pacman package to install the development version:

if (!require("pacman")) install.packages("pacman")

pacman::p_load_current_gh("trinker/lexicon", "trinker/sentimentr")if (!require("pacman")) install.packages("pacman")

pacman::p_load(sentimentr, dplyr, magrittr)Here is a basic sentiment demo. Notice that the first thing you should do is to split your text data into sentences (a process called sentence boundary disambiguation) via the get_sentences function. This can be handled within sentiment (i.e., you can pass a raw character vector) but it slows the function down and should be done one time rather than every time the function is called. Additionally, a warning will be thrown if a larger raw character vector is passed. The preferred workflow is to spit the text into sentences with get_sentences before any sentiment analysis is done.

mytext <- c(

'do you like it? But I hate really bad dogs',

'I am the best friend.',

'Do you really like it? I\'m not a fan'

)

mytext <- get_sentences(mytext)

sentiment(mytext)

## element_id sentence_id word_count sentiment

## 1: 1 1 4 0.2500000

## 2: 1 2 6 -1.8677359

## 3: 2 1 5 0.5813777

## 4: 3 1 5 0.4024922

## 5: 3 2 4 0.0000000To aggregate by element (column cell or vector element) use sentiment_by with by = NULL.

mytext <- c(

'do you like it? But I hate really bad dogs',

'I am the best friend.',

'Do you really like it? I\'m not a fan'

)

mytext <- get_sentences(mytext)

sentiment_by(mytext)

## element_id word_count sd ave_sentiment

## 1: 1 10 1.497465 -0.8088680

## 2: 2 5 NA 0.5813777

## 3: 3 9 0.284605 0.2196345To aggregate by grouping variables use sentiment_by using the by argument.

(out <- with(

presidential_debates_2012,

sentiment_by(

get_sentences(dialogue),

list(person, time)

)

))

## person time word_count sd ave_sentiment

## 1: OBAMA time 1 3599 0.2535006 0.12256892

## 2: OBAMA time 2 7477 0.2509177 0.11217673

## 3: OBAMA time 3 7243 0.2441394 0.07975688

## 4: ROMNEY time 1 4085 0.2525596 0.10151917

## 5: ROMNEY time 2 7536 0.2205169 0.08791018

## 6: ROMNEY time 3 8303 0.2623534 0.09968544

## 7: CROWLEY time 2 1672 0.2181662 0.19455290

## 8: LEHRER time 1 765 0.2973360 0.15473364

## 9: QUESTION time 2 583 0.1756778 0.03197751

## 10: SCHIEFFER time 3 1445 0.2345187 0.08843478Or if you prefer a more tidy approach:

library(magrittr)

library(dplyr)

presidential_debates_2012 %>%

dplyr::mutate(dialogue_split = get_sentences(dialogue)) %$%

sentiment_by(dialogue_split, list(person, time))

## person time word_count sd ave_sentiment

## 1: OBAMA time 1 3599 0.2535006 0.12256892

## 2: OBAMA time 2 7477 0.2509177 0.11217673

## 3: OBAMA time 3 7243 0.2441394 0.07975688

## 4: ROMNEY time 1 4085 0.2525596 0.10151917

## 5: ROMNEY time 2 7536 0.2205169 0.08791018

## 6: ROMNEY time 3 8303 0.2623534 0.09968544

## 7: CROWLEY time 2 1672 0.2181662 0.19455290

## 8: LEHRER time 1 765 0.2973360 0.15473364

## 9: QUESTION time 2 583 0.1756778 0.03197751

## 10: SCHIEFFER time 3 1445 0.2345187 0.08843478Note that you can skip the dplyr::mutate step by using get_sentences on a data.frame as seen below:

presidential_debates_2012 %>%

get_sentences() %$%

sentiment_by(dialogue, list(person, time))

## person time word_count sd ave_sentiment

## 1: OBAMA time 1 3599 0.2535006 0.12256892

## 2: OBAMA time 2 7477 0.2509177 0.11217673

## 3: OBAMA time 3 7243 0.2441394 0.07975688

## 4: ROMNEY time 1 4085 0.2525596 0.10151917

## 5: ROMNEY time 2 7536 0.2205169 0.08791018

## 6: ROMNEY time 3 8303 0.2623534 0.09968544

## 7: CROWLEY time 2 1672 0.2181662 0.19455290

## 8: LEHRER time 1 765 0.2973360 0.15473364

## 9: QUESTION time 2 583 0.1756778 0.03197751

## 10: SCHIEFFER time 3 1445 0.2345187 0.08843478plot(out)

The plot method for the class sentiment uses syuzhet’s get_transformed_values combined with ggplot2 to make a reasonable, smoothed plot for the duration of the text based on percentage, allowing for comparison between plots of different texts. This plot gives the overall shape of the text’s sentiment. The user can see syuzhet::get_transformed_values for more details.

plot(uncombine(out))

It is pretty straight forward to make or update a new dictionary (polarity or valence shifter). To create a key from scratch the user needs to create a 2 column data.frame, with words on the left and values on the right (see ?lexicon::hash_sentiment_jockers_rinker & ?lexicon::hash_valence_shifters for what the values mean). Note that the words need to be lower cased. Here I show an example data.frame ready for key conversion:

set.seed(10)

key <- data.frame(

words = sample(letters),

polarity = rnorm(26),

stringsAsFactors = FALSE

)This is not yet a key. sentimentr provides the is_key function to test if a table is a key.

is_key(key)

## [1] FALSEIt still needs to be data.table-ified. The as_key function coerces a data.frame to a data.table with the left column named x and the right column named y. It also checks the key against another key to make sure there is not overlap using the compare argument. By default as_key checks against valence_shifters_table, assuming the user is creating a sentiment dictionary. If the user is creating a valence shifter key then a sentiment key needs to be passed to compare instead and set the argument sentiment = FALSE. Below I coerce key to a dictionary that sentimentr can use.

mykey <- as_key(key)Now we can check that mykey is a usable dictionary:

is_key(mykey)

## [1] TRUEThe key is ready for use:

sentiment_by("I am a human.", polarity_dt = mykey)

## element_id word_count sd ave_sentiment

## 1: 1 4 NA -0.7594893You can see the values of a key that correspond to a word using data.table syntax:

mykey[c("a", "b")][[2]]

## [1] -0.2537805 -0.1951504Updating (adding or removing terms) a key is also useful. The update_key function allows the user to add or drop terms via the x (add a data.frame) and drop (drop a term) arguments. Below I drop the “a” and “h” terms (notice there are now 24 rows rather than 26):

mykey_dropped <- update_key(mykey, drop = c("a", "h"))

nrow(mykey_dropped)

## [1] 24

sentiment_by("I am a human.", polarity_dt = mykey_dropped)

## element_id word_count sd ave_sentiment

## 1: 1 4 NA -0.632599Next I add the terms “dog” and “cat” as a data.frame with sentiment values:

mykey_added <- update_key(mykey, x = data.frame(x = c("dog", "cat"), y = c(1, -1)))

## Warning in as_key(x, comparison = comparison, sentiment = sentiment): Column 1 was a factor...

## Converting to character.

nrow(mykey_added)

## [1] 28

sentiment("I am a human. The dog. The cat", polarity_dt = mykey_added)

## element_id sentence_id word_count sentiment

## 1: 1 1 4 -0.7594893

## 2: 1 2 2 0.7071068

## 3: 1 3 2 -0.7071068Annie Swafford critiqued Jocker’s approach to sentiment and gave the following examples of sentences (ase for Annie Swafford example). Here I test each of Jocker’s 4 dictionary approaches (syuzhet, Bing, NRC, Afinn), his Stanford wrapper (note I use my own GitHub Stanford wrapper package based off of Jocker’s approach as it works more reliably on my own Windows machine), the RSentiment package, the lookup based SentimentAnalysis package, the meanr package (written in C level code), and my own algorithm with default combined Jockers (2017) & Rinker’s augmented Hu & Liu (2004) polarity lexicons as well as Hu & Liu (2004) and Baccianella, Esuli and Sebastiani’s (2010) SentiWord lexicons available from the lexicon package.

if (!require("pacman")) install.packages("pacman")

pacman::p_load_gh("trinker/sentimentr", "trinker/stansent", "sfeuerriegel/SentimentAnalysis", "wrathematics/meanr")

pacman::p_load(syuzhet, qdap, microbenchmark, RSentiment)

ase <- c(

"I haven't been sad in a long time.",

"I am extremely happy today.",

"It's a good day.",

"But suddenly I'm only a little bit happy.",

"Then I'm not happy at all.",

"In fact, I am now the least happy person on the planet.",

"There is no happiness left in me.",

"Wait, it's returned!",

"I don't feel so bad after all!"

)

syuzhet <- setNames(as.data.frame(lapply(c("syuzhet", "bing", "afinn", "nrc"),

function(x) get_sentiment(ase, method=x))), c("jockers", "bing", "afinn", "nrc"))

SentimentAnalysis <- apply(analyzeSentiment(ase)[c('SentimentGI', 'SentimentLM', 'SentimentQDAP') ], 2, round, 2)

colnames(SentimentAnalysis) <- gsub('^Sentiment', "SA_", colnames(SentimentAnalysis))

left_just(data.frame(

stanford = sentiment_stanford(ase)[["sentiment"]],

sentimentr_jockers_rinker = round(sentiment(ase, question.weight = 0)[["sentiment"]], 2),

sentimentr_jockers = round(sentiment(ase, lexicon::hash_sentiment_jockers, question.weight = 0)[["sentiment"]], 2),

sentimentr_huliu = round(sentiment(ase, lexicon::hash_sentiment_huliu, question.weight = 0)[["sentiment"]], 2),

sentimentr_sentiword = round(sentiment(ase, lexicon::hash_sentiment_sentiword, question.weight = 0)[["sentiment"]], 2),

RSentiment = calculate_score(ase),

SentimentAnalysis,

meanr = score(ase)[['score']],

syuzhet,

sentences = ase,

stringsAsFactors = FALSE

), "sentences")

[1] "Processing sentence: i have not been sad in a long time"

[1] "Processing sentence: i am extremely happy today"

[1] "Processing sentence: its a good day"

[1] "Processing sentence: but suddenly im only a little bit happy"

[1] "Processing sentence: then im not happy at all"

[1] "Processing sentence: in fact i am now the least happy person on the planet"

[1] "Processing sentence: there is no happiness left in me"

[1] "Processing sentence: wait its returned"

[1] "Processing sentence: i do not feel so bad after all"

stanford sentimentr_jockers_rinker sentimentr_jockers sentimentr_huliu

1 -0.5 0.18 0.18 0.35

2 1 0.6 0.6 0.8

3 0.5 0.38 0.38 0.5

4 -0.5 0 0 0

5 -0.5 -0.31 -0.31 -0.41

6 -0.5 0.04 0.04 0.06

7 -0.5 -0.28 -0.28 -0.38

8 0 -0.14 -0.14 0

9 -0.5 0.28 0.28 0.38

sentimentr_sentiword RSentiment SA_GI SA_LM SA_QDAP meanr jockers bing

1 0.18 1 -0.25 0 -0.25 -1 -0.5 -1

2 0.65 1 0.33 0.33 0 1 0.75 1

3 0.32 1 0.5 0.5 0.5 1 0.75 1

4 0 0 0 0.25 0.25 1 0.75 1

5 -0.56 -1 1 1 1 1 0.75 1

6 0.11 1 0.17 0.17 0.33 1 0.75 1

7 -0.05 1 0.5 0.5 0.5 1 0.75 1

8 -0.14 -1 0 0 0 0 -0.25 0

9 0.24 0 -0.33 -0.33 -0.33 -1 -0.75 -1

afinn nrc sentences

1 -2 0 I haven't been sad in a long time.

2 3 1 I am extremely happy today.

3 3 1 It's a good day.

4 3 1 But suddenly I'm only a little bit happy.

5 3 1 Then I'm not happy at all.

6 3 1 In fact, I am now the least happy person on the planet.

7 2 1 There is no happiness left in me.

8 0 -1 Wait, it's returned!

9 -3 -1 I don't feel so bad after all! Also of interest is the computational time used by each of these methods. To demonstrate this I increased Annie’s examples by 100 replications and microbenchmark on a few iterations (Stanford takes so long I didn’t extend to more). Note that if a text needs to be broken into sentence parts syuzhet has the get_sentences function that uses the openNLP package, this is a time expensive task. sentimentr uses a much faster regex based approach that is nearly as accurate in parsing sentences with a much lower computational time. We see that RSentiment and Stanford take the longest time while sentimentr and syuzhet are comparable depending upon lexicon used. meanr is lighting fast. SentimentAnalysis is a bit slower than other methods but is returning 3 scores from 3 different dictionaries. I do not test RSentiment because it causes an out of memory error.

ase_100 <- rep(ase, 100)

stanford <- function() {sentiment_stanford(ase_100)}

sentimentr_jockers_rinker <- function() sentiment(ase_100, lexicon::hash_sentiment_jockers_rinker)

sentimentr_jockers <- function() sentiment(ase_100, lexicon::hash_sentiment_jockers)

sentimentr_huliu <- function() sentiment(ase_100, lexicon::hash_sentiment_huliu)

sentimentr_sentiword <- function() sentiment(ase_100, lexicon::hash_sentiment_sentiword)

RSentiment <- function() calculate_score(ase_100)

SentimentAnalysis <- function() analyzeSentiment(ase_100)

meanr <- function() score(ase_100)

syuzhet_jockers <- function() get_sentiment(ase_100, method="syuzhet")

syuzhet_binn <- function() get_sentiment(ase_100, method="bing")

syuzhet_nrc <- function() get_sentiment(ase_100, method="nrc")

syuzhet_afinn <- function() get_sentiment(ase_100, method="afinn")

microbenchmark(

stanford(),

sentimentr_jockers_rinker(),

sentimentr_jockers(),

sentimentr_huliu(),

sentimentr_sentiword(),

#RSentiment(),

SentimentAnalysis(),

syuzhet_jockers(),

syuzhet_binn(),

syuzhet_nrc(),

syuzhet_afinn(),

meanr(),

times = 3

)

Unit: milliseconds

expr min lq mean

stanford() 20225.158418 20609.912899 23748.607689

sentimentr_jockers_rinker() 283.271569 283.391307 285.273047

sentimentr_jockers() 224.436569 228.487136 235.022980

sentimentr_huliu() 255.438460 260.156352 261.994973

sentimentr_sentiword() 1048.496476 1060.058681 1064.804513

SentimentAnalysis() 4267.380620 4335.857740 4369.068442

syuzhet_jockers() 342.764273 346.408800 349.115379

syuzhet_binn() 258.453721 267.449255 271.441450

syuzhet_nrc() 642.814135 648.150176 653.361347

syuzhet_afinn() 118.191289 120.576642 122.294740

meanr() 1.172578 1.317333 1.795786

median uq max neval

20994.667381 25510.33232 30025.997269 3

283.511045 286.27379 289.036528 3

232.537703 240.31619 248.094669 3

264.874245 265.27323 265.672214 3

1071.620886 1072.95853 1074.296176 3

4404.334860 4419.91235 4435.489845 3

350.053327 352.29093 354.528537 3

276.444790 277.93532 279.425840 3

653.486217 658.63495 663.783689 3

122.961995 124.34647 125.730937 3

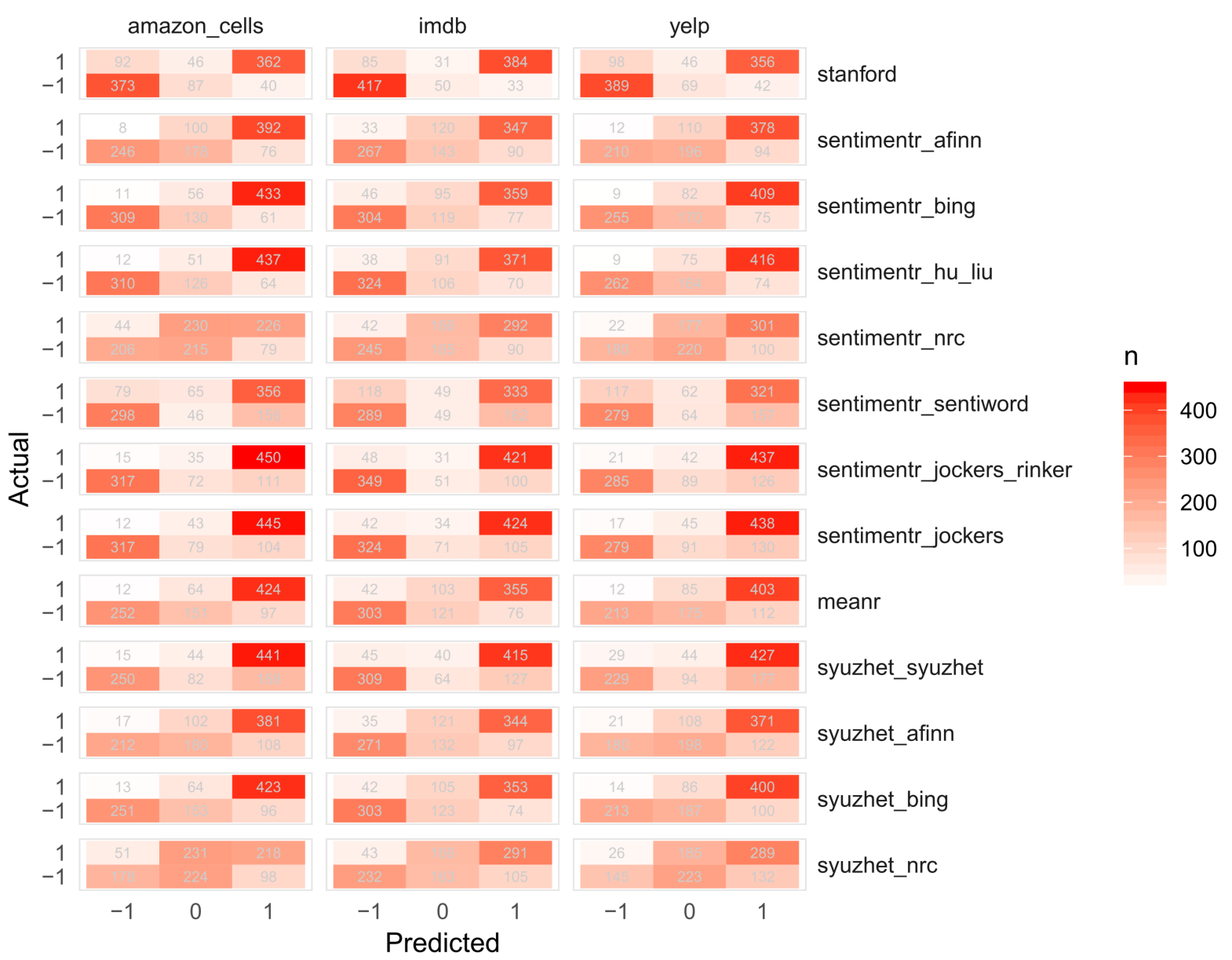

1.462088 2.10739 2.752692 3The accuracy of an algorithm weighs heavily into the decision as to what approach to take in sentiment detection. I have selected algorithms/packages that stand out as fast and/or accurate to perform benchmarking on actual data. The syuzhet package provides multiple dictionaries with a general algorithm to compute sentiment scores. Likewise, sentimentr uses a general algorithm but uses the lexicon package’s dictionaries. syuzhet provides 4 dictionaries while sentimentr uses lexicon’s 9 dictionaries and can be extended easily other dictionaries including the 4 dictionaries from the syuzhet package. meanr is a very fast algorithm. The follow visualization provides the accuracy of these approaches in comparison to Stanford’s Java based implementation of sentiment detection. The visualization is generated from testing on three reviews data sets from Kotzias, Denil, De Freitas, & Smyth (2015). These authors utilized the three 1000 element data sets from:

The data sets are hand scored as either positive or negative. The testing here uses Mean Directional Accuracy (MDA) and merely matches the sign of the algorithm to the human coded output to determine accuracy rates.

The bar graph on the left shows the accuracy rates for the various sentiment set-ups in the three review contexts. The rank plot on the right shows how the rankings for the methods varied across the three review contexts.

The take away here seems that, unsurprisingly, Stanford’s algorithm consistently outscores sentimentr, syuzhet, and meanr. The sentimentr approach loaded with the Jockers’ custom syuzhet dictionary is a top pick for speed and accuracy. In addition to Jockers’ custom dictionary the bing dictionary also performs well within both the syuzhet and sentimentr algorithms. Generally, the sentimentr algorithm out performs syuzhet when their dictionaries are comparable.

It is important to point out that this is a small sample data set that covers a narrow range of uses for sentiment detection. Jockers’ syuzhet was designed to be applied across book chunks and it is, to some extent, unfair to test it out of this context. Still this initial analysis provides a guide that may be of use for selecting the sentiment detection set up most applicable to the reader’s needs.

The reader may access the R script used to generate this visual via:

testing <- system.file("sentiment_testing/sentiment_testing.R", package = "sentimentr")

file.copy(testing, getwd())In the figure below we compare raw table counts as a heat map, plotting the predicted values from the various algorithms on the x axis versus the human scored values on the y axis.

Across all three contexts, notice that the Stanford coreNLP algorithm is better at:

The Jockers, Bing, Hu & Lu, and Afinn dictionaries all do well with regard to not assigning negative scores to positive statements, but perform less well in the reverse, often assigning positive scores to negative statements, though Jockers’ dictionary outperforms the others. We can now see that the reason for the NRC’s poorer performance in accuracy rate above is its inability to discriminate. The Sentiword dictionary does well at discriminating (like Stanford’s coreNLP) but lacks accuracy. We can deduce two things from this observation:

A reworking of the Sentiword dictionary may yield better results for a dictionary lookup approach to sentiment detection, potentially, improving on discrimination and accuracy.

The reader may access the R script used to generate this visual via:

testing2 <- system.file("sentiment_testing/raw_results.R", package = "sentimentr")

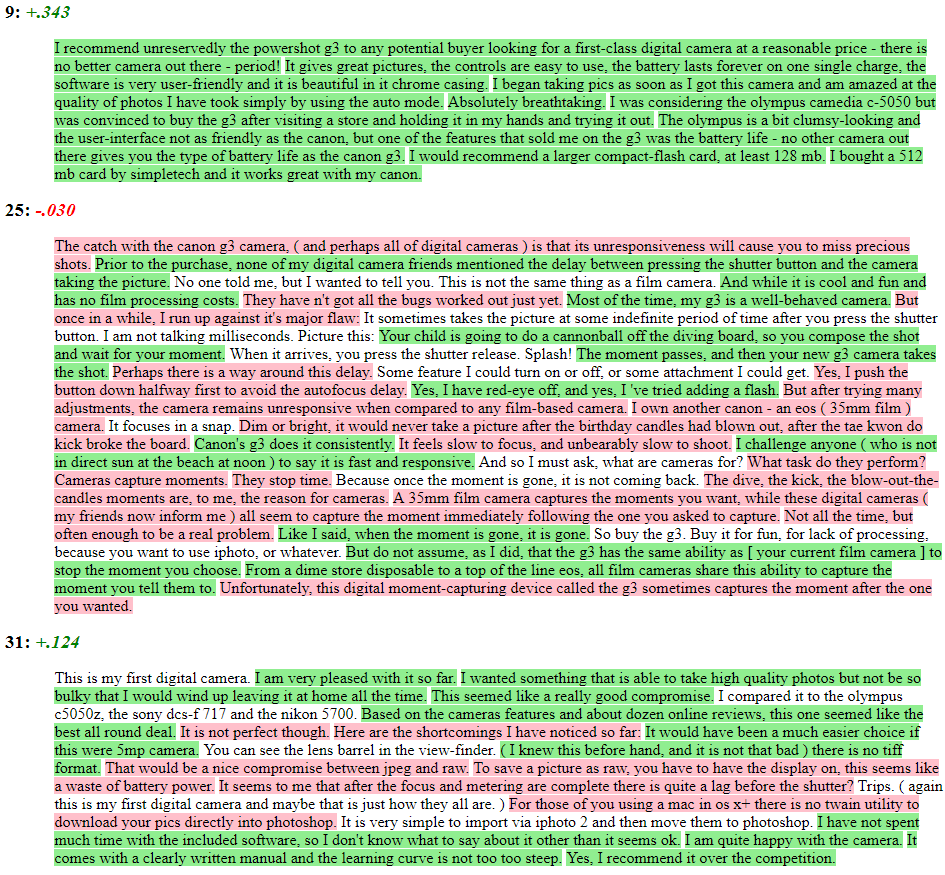

file.copy(testing2, getwd())The user may wish to see the output from sentiment_by line by line with positive/negative sentences highlighted. The highlight function wraps a sentiment_by output to produces a highlighted HTML file (positive = green; negative = pink). Here we look at three random reviews from Hu and Liu’s (2004) Cannon G3 Camera Amazon product reviews.

library(magrittr)

library(dplyr)

set.seed(2)

hu_liu_cannon_reviews %>%

filter(review_id %in% sample(unique(review_id), 3)) %>%

mutate(review = get_sentences(text)) %$%

sentiment_by(review, review_id) %>%

highlight()

You are welcome to:

- submit suggestions and bug-reports at: https://github.com/trinker/sentimentr/issues

- send a pull request on: https://github.com/trinker/sentimentr/

- compose a friendly e-mail to: tyler.rinker@gmail.com