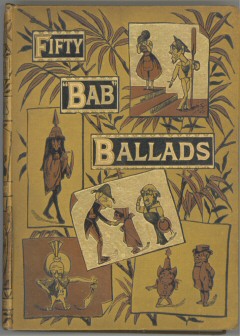

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Fifty Bab Ballads, by W. S. Gilbert This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Fifty Bab Ballads Author: W. S. Gilbert Release Date: August 19, 2019 [eBook #757] [This file was first posted on December 26, 1996] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII) ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FIFTY BAB BALLADS***

Transcribed from the 1884 George Routledge and Sons editions by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

BY

W. S. GILBERT

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY THE AUTHOR [1]

LONDON

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS

BROADWAY, LUDGATE HILL

NEW YORK: 9 LAFAYETTE PLACE

1884

The “Bab Ballads” appeared originally in the columns of “Fun,” when that periodical was under the editorship of the late Tom Hood. They were subsequently republished in two volumes, one called “The Bab Ballads,” the other “More Bab Ballads.” The period during which they were written extended over some three or four years; many, however, were composed hastily, and under the discomforting necessity of having to turn out a quantity of lively verse by a certain day in every week. As it seemed to me (and to others) that the volumes were disfigured by the presence of these hastily written impostors, I thought it better to withdraw from both volumes such Ballads as seemed to show evidence of carelessness or undue haste, and to publish the remainder in the compact form under which they are now presented to the reader.

It may interest some to know that the first of the series, “The Yarn of the Nancy Bell,” was originally offered to “Punch,”—to which I was, at that time, an occasional contributor. It was, however, declined by the then Editor, on the ground that it was “too cannibalistic for his readers’ tastes.”

W. S. GILBERT.

24 The Boltons, South Kensington,

August,

1876.

|

PAGE |

Captain Reece |

|

The Rival Curates |

|

Only a Dancing Girl |

|

To a Little Maid |

|

The Troubadour |

|

Ferdinando and Elvira; or, the Gentle Pieman |

|

To my Bride |

|

Sir Macklin |

|

The Yarn of the “Nancy Bell” |

|

The Bishop of Rum-Ti-Foo |

|

The Precocious Baby |

|

To Phœbe |

|

Baines Carew, Gentleman |

|

Thomas Winterbottom Hance |

|

A Discontented Sugar Broker |

|

The Pantomime “Super” to his Mask |

|

The Ghost, the Gallant, the Gael, and the Goblin |

|

The Phantom Curate |

|

King Borria Bungalee Boo |

|

The Story of Prince Agib |

|

Ellen McJones Aberdeen |

|

Peter the Wag |

|

To the Terrestrial Globe |

|

Gentle Alice Brown |

|

Mister William |

|

The Bumboat Woman’s Story |

|

Lost Mr. Blake |

|

The Baby’s Vengeance |

|

The Captain and the Mermaids |

|

Annie Protheroe. A Legend of Stratford-le-Bow |

|

An Unfortunate Likeness |

|

The King of Canoodle-dum |

|

The Martinet |

|

The Sailor Boy to his Lass |

|

The Reverend Simon Magus |

|

My Dream |

|

The Bishop of Rum-Ti-Foo again |

|

The Haughty Actor |

|

The Two Majors |

|

Emily, John, James, and I. A Derby Legend |

|

The Perils of Invisibility |

|

Phrenology |

|

The Fairy Curate |

|

The Way of Wooing |

|

Hongree and Mahry. A Recollection of a Surrey Melodrama |

|

Etiquette |

|

At a Pantomime |

|

Haunted |

Of all the ships

upon the blue,

No ship contained a better crew

Than that of worthy Captain Reece,

Commanding of The Mantelpiece.

p.

14He was adored by all his men,

For worthy Captain Reece, R.N.,

Did all that lay within him to

Promote the comfort of his crew.

If ever they were dull or sad,

Their captain danced to them like mad,

Or told, to make the time pass by,

Droll legends of his infancy.

A feather bed had every man,

Warm slippers and hot-water can,

Brown windsor from the captain’s store,

A valet, too, to every four.

Did they with thirst in summer burn,

Lo, seltzogenes at every turn,

And on all very sultry days

Cream ices handed round on trays.

Then currant wine and ginger pops

Stood handily on all the “tops;”

And also, with amusement rife,

A “Zoetrope, or Wheel of Life.”

New volumes came across the sea

From Mister Mudie’s libraree;

The Times and Saturday Review

Beguiled the leisure of the crew.

Kind-hearted Captain

Reece, R.N.,

Was quite devoted to his men;

In point of fact, good Captain

Reece

Beatified The Mantelpiece.

p.

15One summer eve, at half-past ten,

He said (addressing all his men):

“Come, tell me, please, what I can do

To please and gratify my crew.

“By any reasonable plan

I’ll make you happy if I can;

My own convenience count as nil:

It is my duty, and I will.”

Then up and answered William Lee

(The kindly captain’s coxswain he,

A nervous, shy, low-spoken man),

He cleared his throat and thus began:

“You have a daughter, Captain Reece,

Ten female cousins and a niece,

A Ma, if what I’m told is true,

Six sisters, and an aunt or two.

“Now, somehow, sir, it seems to me,

More friendly-like we all should be,

If you united of ’em to

Unmarried members of the crew.

“If you’d ameliorate our life,

Let each select from them a wife;

And as for nervous me, old pal,

Give me your own enchanting gal!”

Good Captain Reece,

that worthy man,

Debated on his coxswain’s plan:

“I quite agree,” he said, “O Bill;

It is my duty, and I will.

p.

16“My daughter, that enchanting gurl,

Has just been promised to an Earl,

And all my other familee

To peers of various degree.

“But what are dukes and viscounts to

The happiness of all my crew?

The word I gave you I’ll fulfil;

It is my duty, and I will.

“As you desire it shall befall,

I’ll settle thousands on you all,

And I shall be, despite my hoard,

The only bachelor on board.”

The boatswain of The Mantelpiece,

He blushed and spoke to Captain

Reece:

“I beg your honour’s leave,” he said;

“If you would wish to go and wed,

p.

17“I have a widowed mother who

Would be the very thing for you—

She long has loved you from afar:

She washes for you, Captain

R.”

The Captain saw the dame that day—

Addressed her in his playful way—

“And did it want a wedding ring?

It was a tempting ickle sing!

“Well, well, the chaplain I will seek,

We’ll all be married this day week

At yonder church upon the hill;

It is my duty, and I will!”

The sisters, cousins, aunts, and niece,

And widowed Ma of Captain Reece,

Attended there as they were bid;

It was their duty, and they did.

List while the poet

trolls

Of Mr. Clayton Hooper,

Who had a cure of souls

At Spiffton-extra-Sooper.

He lived on curds and whey,

And daily sang their praises,

And then he’d go and play

With buttercups and daisies.

Wild croquêt Hooper banned,

And all the sports of Mammon,

He warred with cribbage, and

He exorcised backgammon.

His helmet was a glance

That spoke of holy gladness;

A saintly smile his lance;

His shield a tear of sadness.

His Vicar smiled to see

This armour on him buckled:

With pardonable glee

He blessed himself and chuckled.

p.

19“In mildness to abound

My curate’s sole design is;

In all the country round

There’s none so mild as mine is!”

And Hooper,

disinclined

His trumpet to be blowing,

Yet didn’t think you’d find

A milder curate going.

A friend arrived one day

At Spiffton-extra-Sooper,

And in this shameful way

He spoke to Mr. Hooper:

“You think your famous name

For mildness can’t be shaken,

That none can blot your fame—

But, Hooper, you’re

mistaken!

p.

20“Your mind is not as blank

As that of Hopley

Porter,

Who holds a curate’s rank

At Assesmilk-cum-Worter.

“He plays the airy flute,

And looks depressed and blighted,

Doves round about him ‘toot,’

And lambkins dance delighted.

“He labours more than you

At worsted work, and frames it;

In old maids’ albums, too,

Sticks seaweed—yes, and names it!”

The tempter said his say,

Which pierced him like a needle—

He summoned straight away

His sexton and his beadle.

p.

21(These men were men who could

Hold liberal opinions:

On Sundays they were good—

On week-days they were minions.)

“To Hopley

Porter go,

Your fare I will afford you—

Deal him a deadly blow,

And blessings shall reward you.

“But stay—I do not like

Undue assassination,

And so before you strike,

Make this communication:

“I’ll give him this one

chance—

If he’ll more gaily bear him,

Play croquêt, smoke, and dance,

I willingly will spare him.”

p.

22They went, those minions true,

To Assesmilk-cum-Worter,

And told their errand to

The Reverend Hopley

Porter.

“What?” said that reverend gent,

“Dance through my hours of leisure?

Smoke?—bathe myself with scent?—

Play croquêt? Oh, with pleasure!

“Wear all my hair in curl?

Stand at my door and wink—so—

At every passing girl?

My brothers, I should think so!

“For years I’ve longed for some

Excuse for this revulsion:

Now that excuse has come—

I do it on compulsion!!!”

p.

23He smoked and winked away—

This Reverend Hopley

Porter—

The deuce there was to pay

At Assesmilk-cum-Worter.

And Hooper holds his

ground,

In mildness daily growing—

They think him, all around,

The mildest curate going.

Only a dancing

girl,

With an unromantic style,

With borrowed colour and curl,

With fixed mechanical smile,

With many a hackneyed wile,

With ungrammatical lips,

And corns that mar her trips.

p.

25Hung from the “flies” in air,

She acts a palpable lie,

She’s as little a fairy there

As unpoetical I!

I hear you asking, Why—

Why in the world I sing

This tawdry, tinselled thing?

No airy fairy she,

As she hangs in arsenic green

From a highly impossible tree

In a highly impossible scene

(Herself not over-clean).

For fays don’t suffer, I’m told,

From bunions, coughs, or cold.

And stately dames that bring

Their daughters there to see,

Pronounce the “dancing thing”

No better than she should be,

With her skirt at her shameful knee,

And her painted, tainted phiz:

Ah, matron, which of us is?

(And, in sooth, it oft occurs

That while these matrons sigh,

Their dresses are lower than hers,

And sometimes half as high;

And their hair is hair they buy,

And they use their glasses, too,

In a way she’d blush to do.)

p.

26But change her gold and green

For a coarse merino gown,

And see her upon the scene

Of her home, when coaxing down

Her drunken father’s frown,

In his squalid cheerless den:

She’s a fairy truly, then!

Come with me, little

maid,

Nay, shrink not, thus afraid—

I’ll harm thee not!

Fly not, my love, from me—

I have a home for thee—

A fairy grot,

Where mortal

eye

Can rarely

pry,

There shall thy dwelling be!

List to me, while I tell

The pleasures of that cell,

Oh, little maid!

What though its couch be rude,

Homely the only food

Within its shade?

No thought of

care

Can enter

there,

No vulgar swain intrude!

Come with me, little maid,

Come to the rocky shade

I love to sing;

Live with us, maiden rare—

Come, for we “want” thee there,

Thou elfin thing,

To work thy

spell,

In some cool

cell

In stately Pentonville!

A troubadour he

played

Without a castle wall,

Within, a hapless maid

Responded to his call.

“Oh, willow, woe is me!

Alack and well-a-day!

If I were only free

I’d hie me far away!”

p.

29Unknown her face and name,

But this he knew right well,

The maiden’s wailing came

From out a dungeon cell.

A hapless woman lay

Within that dungeon grim—

That fact, I’ve heard him say,

Was quite enough for him.

“I will not sit or lie,

Or eat or drink, I vow,

Till thou art free as I,

Or I as pent as thou.”

Her tears then ceased to flow,

Her wails no longer rang,

And tuneful in her woe

The prisoned maiden sang:

“Oh, stranger, as you play,

I recognize your touch;

And all that I can say

Is, thank you very much.”

He seized his clarion straight,

And blew thereat, until

A warden oped the gate.

“Oh, what might be your will?”

“I’ve come, Sir Knave, to see

The master of these halls:

A maid unwillingly

Lies prisoned in their walls.”’

p.

30With barely stifled sigh

That porter drooped his head,

With teardrops in his eye,

“A many, sir,” he said.

He stayed to hear no more,

But pushed that porter by,

And shortly stood before

Sir Hugh de Peckham

Rye.

Sir Hugh he darkly

frowned,

“What would you, sir, with me?”

The troubadour he downed

Upon his bended knee.

“I’ve come, de

Peckham Rye,

To do a Christian task;

You ask me what would I?

It is not much I ask.

“Release these maidens, sir,

Whom you dominion o’er—

Particularly her

Upon the second floor.

p.

31“And if you don’t, my lord”—

He here stood bolt upright,

And tapped a tailor’s sword—

“Come out, you cad, and fight!”

Sir Hugh he

called—and ran

The warden from the gate:

“Go, show this gentleman

The maid in Forty-eight.”

By many a cell they past,

And stopped at length before

A portal, bolted fast:

The man unlocked the door.

He called inside the gate

With coarse and brutal shout,

“Come, step it, Forty-eight!”

And Forty-eight stepped out.

p.

32“They gets it pretty hot,

The maidens what we cotch—

Two years this lady’s got

For collaring a wotch.”

“Oh, ah!—indeed—I

see,”

The troubadour exclaimed—

“If I may make so free,

How is this castle named?”

The warden’s eyelids fill,

And sighing, he replied,

“Of gloomy Pentonville

This is the female side!”

The minstrel did not wait

The Warden stout to thank,

But recollected straight

He’d business at the Bank.

At a pleasant

evening party I had taken down to supper

One whom I will call Elvira, and we

talked of love and Tupper,

Mr. Tupper and the

Poets, very lightly with them dealing,

For I’ve always been distinguished for a strong poetic

feeling.

Then we let off paper crackers, each of which

contained a motto,

And she listened while I read them, till her mother told her not

to.

Then she whispered, “To the ball-room we

had better, dear, be walking;

If we stop down here much longer, really people will be

talking.”

There were noblemen in coronets, and military

cousins,

There were captains by the hundred, there were baronets by

dozens.

Yet she heeded not their offers, but dismissed

them with a blessing,

Then she let down all her back hair, which had taken long in

dressing.

Then she had convulsive sobbings in her

agitated throttle,

Then she wiped her pretty eyes and smelt her pretty

smelling-bottle.

p.

34So I whispered, “Dear Elvira, say,—what can the matter be

with you?

Does anything you’ve eaten, darling Popsy, disagree with you?”

But spite of all I said, her sobs grew more and

more distressing,

And she tore her pretty back hair, which had taken long in

dressing.

Then she gazed upon the carpet, at the ceiling,

then above me,

And she whispered, “Ferdinando,

do you really, really love me?”

“Love you?” said I, then I sighed,

and then I gazed upon her sweetly—

For I think I do this sort of thing particularly neatly.

“Send me to the Arctic regions, or

illimitable azure,

On a scientific goose-chase, with my Coxwell or my Glaisher!

“Tell me whither I may hie me—tell

me, dear one, that I may know—

Is it up the highest Andes? down a horrible volcano?”

But she said, “It isn’t polar

bears, or hot volcanic grottoes:

Only find out who it is that writes those lovely cracker

mottoes!”

“Tell me, Henry

Wadsworth, Alfred Poet Close,

or Mister Tupper,

Do you write the bon bon mottoes my Elvira pulls at supper?”

But Henry Wadsworth

smiled, and said he had not had that honour;

And Alfred, too, disclaimed the words

that told so much upon her.

p.

35“Mister Martin Tupper,

Poet Close, I beg of you inform

us;”

But my question seemed to throw them both into a rage

enormous.

Mister Close

expressed a wish that he could only get anigh to me;

And Mister Martin Tupper sent the

following reply to me:

“A fool is bent upon a twig, but wise men

dread a bandit,”—

Which I know was very clever; but I didn’t understand

it.

Seven weary years I wandered—Patagonia,

China, Norway,

Till at last I sank exhausted at a pastrycook his doorway.

There were fuchsias and geraniums, and

daffodils and myrtle,

So I entered, and I ordered half a basin of mock turtle.

He was plump and he was chubby, he was smooth

and he was rosy,

And his little wife was pretty and particularly cosy.

And he chirped and sang, and skipped about, and

laughed with laughter hearty—

He was wonderfully active for so very stout a party.

And I said, “O gentle pieman, why so

very, very merry?

Is it purity of conscience, or your one-and-seven

sherry?”

But he answered, “I’m so

happy—no profession could be dearer—

If I am not humming ‘Tra! la! la!’ I’m singing

‘Tirer, lirer!’

“First I go and make the patties, and the

puddings, and the jellies,

Then I make a sugar bird-cage, which upon a table swell is;

“Then I polish all the silver, which a

supper-table lacquers;

Then I write the pretty mottoes which you find inside the

crackers.”—

p.

36“Found at last!” I madly shouted.

“Gentle pieman, you astound me!”

Then I waved the turtle soup enthusiastically round me.

And I shouted and I danced until he’d

quite a crowd around him—

And I rushed away exclaiming, “I have found him! I

have found him!”

And I heard the gentle pieman in the road

behind me trilling,

“‘Tira, lira!’ stop him, stop him!

‘Tra! la! la!’ the soup’s a

shilling!”

But until I reached Elvira’s home, I never, never

waited,

And Elvira to her Ferdinand’s irrevocably mated!

Oh! little

maid!—(I do not know your name

Or who you are, so, as a safe precaution

I’ll add)—Oh, buxom widow! married dame!

(As one of these must be your present portion)

Listen, while I unveil prophetic

lore for you,

And sing the fate that Fortune has

in store for you.

You’ll marry soon—within a year or

twain—

A bachelor of circa two and thirty:

Tall, gentlemanly, but extremely plain,

And when you’re intimate, you’ll call

him “Bertie.”

Neat—dresses well; his

temper has been classified

As hasty; but he’s very

quickly pacified.

You’ll find him working mildly at the

Bar,

After a touch at two or three professions,

From easy affluence extremely far,

A brief or two on Circuit—“soup”

at Sessions;

A pound or two from whist and

backing horses,

And, say three hundred from his

own resources.

p.

38Quiet in harness; free from serious vice,

His faults are not particularly shady,

You’ll never find him “shy”—for,

once or twice

Already, he’s been driven by a lady,

Who parts with him—perhaps a

poor excuse for him—

Because she hasn’t any

further use for him.

Oh! bride of mine—tall, dumpy, dark, or

fair!

Oh! widow—wife, maybe, or blushing maiden,

I’ve told your fortune; solved the gravest care

With which your mind has hitherto been laden.

I’ve prophesied correctly,

never doubt it;

Now tell me mine—and please

be quick about it!

You—only you—can tell me, an’

you will,

To whom I’m destined shortly to be mated,

Will she run up a heavy modiste’s bill?

If so, I want to hear her income stated

(This is a point which interests

me greatly).

To quote the bard, “Oh! have

I seen her lately?”

Say, must I wait till husband number one

Is comfortably stowed away at Woking?

How is her hair most usually done?

And tell me, please, will she object to smoking?

The colour of her eyes, too, you

may mention:

Come, Sibyl,

prophesy—I’m all attention.

Of all the youths I

ever saw

None were so wicked, vain, or silly,

So lost to shame and Sabbath law,

As worldly Tom, and Bob, and Billy.

For every Sabbath day they walked

(Such was their gay and thoughtless natur)

In parks or gardens, where they talked

From three to six, or even later.

Sir Macklin was a

priest severe

In conduct and in conversation,

It did a sinner good to hear

Him deal in ratiocination.

He could in every action show

Some sin, and nobody could doubt him.

He argued high, he argued low,

He also argued round about him.

p.

40He wept to think each thoughtless youth

Contained of wickedness a skinful,

And burnt to teach the awful truth,

That walking out on Sunday’s sinful.

“Oh, youths,” said he, “I

grieve to find

The course of life you’ve been and hit

on—

Sit down,” said he, “and never mind

The pennies for the chairs you sit on.

“My opening head is

‘Kensington,’

How walking there the sinner hardens,

Which when I have enlarged upon,

I go to ‘Secondly’—its

‘Gardens.’

“My ‘Thirdly’ comprehendeth

‘Hyde,’

Of Secresy the guilts and shameses;

My ‘Fourthly’—‘Park’—its

verdure wide—

My ‘Fifthly’ comprehends ‘St.

James’s.’

p.

41“That matter settled, I shall reach

The ‘Sixthly’ in my solemn tether,

And show that what is true of each,

Is also true of all, together.

“Then I shall demonstrate to you,

According to the rules of Whately,

That what is true of all, is true

Of each, considered separately.”

In lavish stream his accents flow,

Tom, Bob, and Billy

dare not flout him;

He argued high, he argued low,

He also argued round about him.

“Ha, ha!” he said, “you

loathe your ways,

You writhe at these my words of warning,

In agony your hands you raise.”

(And so they did, for they were yawning.)

p.

42To “Twenty-firstly” on they go,

The lads do not attempt to scout him;

He argued high, he argued low,

He also argued round about him.

“Ho, ho!” he cries, “you bow

your crests—

My eloquence has set you weeping;

In shame you bend upon your breasts!”

(And so they did, for they were sleeping.)

He proved them this—he proved them

that—

This good but wearisome ascetic;

He jumped and thumped upon his hat,

He was so very energetic.

His Bishop at this moment chanced

To pass, and found the road encumbered;

He noticed how the Churchman danced,

And how his congregation slumbered.

p.

43The hundred and eleventh head

The priest completed of his stricture;

“Oh, bosh!” the worthy Bishop said,

And walked him off as in the picture.

’Twas on the

shores that round our coast

From Deal to Ramsgate span,

That I found alone on a piece of stone

An elderly naval man.

His hair was weedy, his beard was long,

And weedy and long was he,

And I heard this wight on the shore recite,

In a singular minor key:

“Oh, I am a cook and a captain bold,

And the mate of the Nancy brig,

And a bo’sun tight, and a midshipmite,

And the crew of the captain’s gig.”

And he shook his fists and he tore his hair,

Till I really felt afraid,

For I couldn’t help thinking the man had been drinking,

And so I simply said:

p.

45“Oh, elderly man, it’s little I know

Of the duties of men of the sea,

And I’ll eat my hand if I understand

However you can be

“At once a cook, and a captain bold,

And the mate of the Nancy brig,

And a bo’sun tight, and a midshipmite,

And the crew of the captain’s gig.”

Then he gave a hitch to his trousers, which

Is a trick all seamen larn,

And having got rid of a thumping quid,

He spun this painful yarn:

“’Twas in the good ship Nancy

Bell

That we sailed to the Indian Sea,

And there on a reef we come to grief,

Which has often occurred to me.

“And pretty nigh all the crew was

drowned

(There was seventy-seven o’ soul),

And only ten of the Nancy’s men

Said ‘Here!’ to the muster-roll.

“There was me and the cook and the

captain bold,

And the mate of the Nancy brig,

And the bo’sun tight, and a midshipmite,

And the crew of the captain’s gig.

“For a month we’d neither wittles

nor drink,

Till a-hungry we did feel,

So we drawed a lot, and, accordin’ shot

The captain for our meal.

p.

46“The next lot fell to the Nancy’s

mate,

And a delicate dish he made;

Then our appetite with the midshipmite

We seven survivors stayed.

“And then we murdered the bo’sun

tight,

And he much resembled pig;

Then we wittled free, did the cook and me,

On the crew of the captain’s gig.

“Then only the cook and me was left,

And the delicate question, ‘Which

Of us two goes to the kettle?’ arose,

And we argued it out as sich.

“For I loved that cook as a brother, I

did,

And the cook he worshipped me;

But we’d both be blowed if we’d either be stowed

In the other chap’s hold, you see.

“‘I’ll be eat if you dines

off me,’ says Tom;

‘Yes, that,’ says I, ‘you’ll

be,—

‘I’m boiled if I die, my friend,’ quoth I;

And ‘Exactly so,’ quoth he.

“Says he, ‘Dear James, to murder me

Were a foolish thing to do,

For don’t you see that you can’t cook me,

While I can—and will—cook

you!’

“So he boils the water, and takes the

salt

And the pepper in portions true

(Which he never forgot), and some chopped shalot.

And some sage and parsley too.

p.

47“‘Come here,’ says he, with a proper

pride,

Which his smiling features tell,

‘’T will soothing be if I let you see

How extremely nice you’ll smell.’

“And he stirred it round and round and

round,

And he sniffed at the foaming froth;

When I ups with his heels, and smothers his squeals

In the scum of the boiling broth.

“And I eat that cook in a week or

less,

And—as I eating be

The last of his chops, why, I almost drops,

For a wessel in sight I see!

* * * *

“And I never larf, and I never smile,

And I never lark nor play,

But sit and croak, and a single joke

I have—which is to say:

“Oh, I am a cook and a captain bold,

And the mate of the Nancy brig,

And a bo’sun tight, and a midshipmite,

And the crew of the captain’s

gig!’”

From east and south

the holy clan

Of Bishops gathered to a man;

To Synod, called Pan-Anglican,

In flocking crowds they came.

Among them was a Bishop, who

Had lately been appointed to

The balmy isle of Rum-ti-Foo,

And Peter was his

name.

His people—twenty-three in sum—

They played the eloquent tum-tum,

And lived on scalps served up, in rum—

The only sauce they knew.

p. 49When first

good Bishop Peter came

(For Peter was that Bishop’s

name),

To humour them, he did the same

As they of Rum-ti-Foo.

His flock, I’ve often heard him tell,

(His name was Peter) loved him

well,

And, summoned by the sound of bell,

In crowds together came.

“Oh, massa, why you go away?

Oh, Massa Peter, please to

stay.”

(They called him Peter, people say,

Because it was his name.)

He told them all good boys to be,

And sailed away across the sea,

At London Bridge that Bishop he

Arrived one Tuesday night;

And as that night he homeward strode

To his Pan-Anglican abode,

He passed along the Borough Road,

And saw a gruesome sight.

He saw a crowd assembled round

A person dancing on the ground,

Who straight began to leap and bound

With all his might and main.

To see that dancing man he stopped,

Who twirled and wriggled, skipped and hopped,

Then down incontinently dropped,

And then sprang up again.

p.

50The Bishop chuckled at the sight.

“This style of dancing would delight

A simple Rum-ti-Foozleite.

I’ll learn it if I can,

To please the tribe when I get back.”

He begged the man to teach his knack.

“Right Reverend Sir, in half a crack!”

Replied that dancing man.

The dancing man he worked away,

And taught the Bishop every day—

The dancer skipped like any fay—

Good Peter did the

same.

The Bishop buckled to his task,

With battements, and pas de basque.

(I’ll tell you, if you care to ask,

That Peter was his

name.)

p.

51“Come, walk like this,” the dancer said,

“Stick out your toes—stick in your head,

Stalk on with quick, galvanic tread—

Your fingers thus extend;

The attitude’s considered quaint.”

The weary Bishop, feeling faint,

Replied, “I do not say it ain’t,

But ‘Time!’ my Christian

friend!”

“We now proceed to something

new—

Dance as the Paynes and Lauris do,

Like this—one, two—one, two—one, two.”

The Bishop, never proud,

But in an overwhelming heat

(His name was Peter, I repeat)

Performed the Payne and Lauri feat,

And puffed his thanks aloud.

p.

52Another game the dancer planned—

“Just take your ankle in your hand,

And try, my lord, if you can stand—

Your body stiff and stark.

If, when revisiting your see,

You learnt to hop on shore—like me—

The novelty would striking be,

And must attract remark.”

“No,” said the worthy Bishop,

“no;

That is a length to which, I trow,

Colonial Bishops cannot go.

You may express surprise

At finding Bishops deal in pride—

But if that trick I ever tried,

I should appear undignified

In Rum-ti-Foozle’s eyes.

p.

53“The islanders of Rum-ti-Foo

Are well-conducted persons, who

Approve a joke as much as you,

And laugh at it as such;

But if they saw their Bishop land,

His leg supported in his hand,

The joke they wouldn’t understand—

’T would pain them very much!”

(To be sung to the Air of the “Whistling Oyster.”)

An elderly

person—a prophet by trade—

With his quips

and tips

On withered old

lips,

He married a young and a beautiful maid;

The cunning old

blade!

Though rather

decayed,

He married a beautiful, beautiful maid.

p.

55She was only eighteen, and as fair as could be,

With her

tempting smiles

And maidenly

wiles,

And he was a trifle past seventy-three:

Now what she

could see

Is a puzzle to

me,

In a prophet of seventy—seventy-three!

Of all their acquaintances bidden (or bad)

With their loud

high jinks

And underbred

winks,

None thought they’d a family have—but they had;

A dear little

lad

Who drove

’em half mad,

For he turned out a horribly fast little cad.

For when he was born he astonished all by,

With their

“Law, dear me!”

“Did ever

you see?”

He’d a pipe in his mouth and a glass in his eye,

A hat all

awry—

An octagon

tie—

And a miniature—miniature glass in his eye.

He grumbled at wearing a frock and a cap,

With his

“Oh, dear, oh!”

And his

“Hang it! ’oo know!”

And he turned up his nose at his excellent pap—

“My

friends, it’s a tap

Dat is not worf

a rap.”

(Now this was remarkably excellent pap.)

p.

56He’d chuck his nurse under the chin, and

he’d say,

With his

“Fal, lal, lal”—

“’Oo

doosed fine gal!”

This shocking precocity drove ’em away:

“A month

from to-day

Is as long as

I’ll stay—

Then I’d wish, if you please, for to toddle

away.”

His father, a simple old gentleman, he

With nursery

rhyme

And “Once

on a time,”

Would tell him the story of “Little Bo-P,”

“So pretty

was she,

So pretty and

wee,

As pretty, as pretty, as pretty could be.”

p.

57But the babe, with a dig that would startle an ox,

With his

“C’ck! Oh, my!—

Go along wiz

’oo, fie!”

Would exclaim, “I’m afraid ’oo a socking ole

fox.”

Now a father it

shocks,

And it whitens

his locks,

When his little babe calls him a shocking old fox.

The name of his father he’d couple and

pair

(With his

ill-bred laugh,

And insolent

chaff)

With those of the nursery heroines rare—

Virginia the

Fair,

Or Good

Goldenhair,

Till the nuisance was more than a prophet could bear.

“There’s Jill and White Cat”

(said the bold little brat,

With his loud,

“Ha, ha!”)

“’Oo

sly ickle Pa!

Wiz ’oo Beauty, Bo-Peep, and ’oo Mrs. Jack Sprat!

I’ve

noticed ’oo pat

My pretty

White Cat—

I sink dear mamma ought to know about dat!”

He early determined to marry and wive,

For better or

worse

With his elderly

nurse—

Which the poor little boy didn’t live to contrive:

His hearth

didn’t thrive—

No longer

alive,

He died an enfeebled old dotard at five!

Now, elderly men of the bachelor crew,

With wrinkled

hose

And spectacled

nose,

Don’t marry at all—you may take it as true

If ever you

do

The step you

will rue,

For your babes will be elderly—elderly too.

“Gentle,

modest little flower,

Sweet epitome of May,

Love me but for half an hour,

Love me, love me, little fay.”

Sentences so fiercely flaming

In your tiny shell-like ear,

I should always be exclaiming

If I loved you, Phœbe dear.

“Smiles that thrill from any distance

Shed upon me while I sing!

Please ecstaticize existence,

Love me, oh, thou fairy thing!”

Words like these, outpouring sadly

You’d perpetually hear,

If I loved you fondly, madly;—

But I do not, Phœbe

dear.

Of all the good

attorneys who

Have placed their names upon the roll,

But few could equal Baines Carew

For tender-heartedness and soul.

Whene’er he heard a tale of woe

From client A or client B,

His grief would overcome him so

He’d scarce have strength to take his fee.

p.

61It laid him up for many days,

When duty led him to distrain,

And serving writs, although it pays,

Gave him excruciating pain.

He made out costs, distrained for rent,

Foreclosed and sued, with moistened eye—

No bill of costs could represent

The value of such sympathy.

No charges can approximate

The worth of sympathy with woe;—

Although I think I ought to state

He did his best to make them so.

Of all the many clients who

Had mustered round his legal flag,

No single client of the crew

Was half so dear as Captain

Bagg.

Now, Captain Bagg

had bowed him to

A heavy matrimonial yoke—

His wifey had of faults a few—

She never could resist a joke.

Her chaff at first he meekly bore,

Till unendurable it grew.

“To stop this persecution sore

I will consult my friend Carew.

“And when Carew’s advice I’ve got,

Divorce a mensâ I shall try.”

(A legal separation—not

A vinculo conjugii.)

p.

62“Oh, Baines Carew, my

woe I’ve kept

A secret hitherto, you know;”—

(And Baines Carew, Esquire, he wept

To hear that Bagg

had any woe.)

“My case, indeed, is passing sad.

My wife—whom I considered true—

With brutal conduct drives me mad.”

“I am appalled,” said Baines Carew.

“What! sound the matrimonial knell

Of worthy people such as these!

Why was I an attorney? Well—

Go on to the sævitia,

please.”

“Domestic bliss has proved my

bane,—

A harder case you never heard,

My wife (in other matters sane)

Pretends that I’m a Dicky bird!

p.

63“She makes me sing, ‘Too-whit,

too-wee!’

And stand upon a rounded stick,

And always introduces me

To every one as ‘Pretty

Dick’!”

“Oh, dear,” said weeping Baines Carew,

“This is the direst case I know.”

“I’m grieved,” said Bagg, “at paining you—

To Cobb and Poltherthwaite I’ll go—

“To Cobb’s cold, calculating ear,

My gruesome sorrows I’ll

impart”—

“No; stop,” said Baines,

“I’ll dry my tear,

And steel my sympathetic heart.”

“She makes me perch upon a tree,

Rewarding me with

‘Sweety—nice!’

And threatens to exhibit me

With four or five performing mice.”

“Restrain my tears I wish I

could”

(Said Baines), “I

don’t know what to do.”

Said Captain Bagg, “You’re

very good.”

“Oh, not at all,” said Baines Carew.

p.

64“She makes me fire a gun,” said Bagg;

“And, at a preconcerted word,

Climb up a ladder with a flag,

Like any street performing bird.

“She places sugar in my way—

In public places calls me ‘Sweet!’

She gives me groundsel every day,

And hard canary-seed to eat.”

“Oh, woe! oh, sad! oh, dire to

tell!”

(Said Baines).

“Be good enough to stop.”

And senseless on the floor he fell,

With unpremeditated flop!

Said Captain Bagg,

“Well, really I

Am grieved to think it pains you so.

I thank you for your sympathy;

But, hang it!—come—I say, you

know!”

p.

65But Baines lay flat upon the

floor,

Convulsed with sympathetic sob;—

The Captain toddled off next door,

And gave the case to Mr.

Cobb.

In all the towns and

cities fair

On Merry England’s broad expanse,

No swordsman ever could compare

With Thomas Winterbottom

Hance.

The dauntless lad could fairly hew

A silken handkerchief in twain,

Divide a leg of mutton too—

And this without unwholesome strain.

p.

67On whole half-sheep, with cunning trick,

His sabre sometimes he’d employ—

No bar of lead, however thick,

Had terrors for the stalwart boy.

At Dover daily he’d prepare

To hew and slash, behind, before—

Which aggravated Monsieur Pierre,

Who watched him from the Calais shore.

It caused good Pierre to swear and dance,

The sight annoyed and vexed him so;

He was the bravest man in France—

He said so, and he ought to know.

p.

68“Regardez donc, ce cochon gros—

Ce polisson! Oh, sacré bleu!

Son sabre, son plomb, et ses gigots

Comme cela m’ennuye, enfin, mon Dieu!

“Il sait que les foulards de soie

Give no retaliating whack—

Les gigots morts n’ont pas de quoi—

Le plomb don’t ever hit you back.”

But every day the headstrong lad

Cut lead and mutton more and more;

And every day poor Pierre, half

mad,

Shrieked loud defiance from his shore.

Hance had a mother,

poor and old,

A simple, harmless village dame,

Who crowed and clapped as people told

Of Winterbottom’s

rising fame.

She said, “I’ll be upon the spot

To see my Tommy’s

sabre-play;”

And so she left her leafy cot,

And walked to Dover in a day.

Pierre had a doating

mother, who

Had heard of his defiant rage;

His Ma was nearly ninety-two,

And rather dressy for her age.

p.

69At Hance’s doings every

morn,

With sheer delight his mother cried;

And Monsieur Pierre’s

contemptuous scorn

Filled his mamma with proper pride.

But Hance’s

powers began to fail—

His constitution was not strong—

And Pierre, who once was stout and

hale,

Grew thin from shouting all day long.

Their mothers saw them pale and wan,

Maternal anguish tore each breast,

And so they met to find a plan

To set their offsprings’ minds at rest.

Said Mrs. Hance,

“Of course I shrinks

From bloodshed, ma’am, as you’re

aware,

But still they’d better meet, I thinks.”

“Assurément!” said Madame Pierre.

p.

70A sunny spot in sunny France

Was hit upon for this affair;

The ground was picked by Mrs.

Hance,

The stakes were pitched by Madame Pierre.

Said Mrs. H.,

“Your work you see—

Go in, my noble boy, and win.”

“En garde, mon fils!” said Madame P.

“Allons!” “Go

on!” “En garde!”

“Begin!”

(The mothers were of decent size,

Though not particularly tall;

But in the sketch that meets your eyes

I’ve been obliged to draw them small.)

p.

71Loud sneered the doughty man of France,

“Ho! ho! Ho! ho! Ha! ha! Ha!

ha!

The French for ‘Pish’” said Thomas Hance.

Said Pierre,

“L’Anglais, Monsieur, pour

‘Bah.’”

Said Mrs. H.,

“Come, one! two! three!—

We’re sittin’ here to see all

fair.”

“C’est magnifique!” said Madame P.,

“Mais, parbleu! ce n’est pas la

guerre!”

“Je scorn un foe si lache que

vous,”

Said Pierre, the doughty

son of France.

“I fight not coward foe like you!”

Said our undaunted Tommy

Hance.

“The French for

‘Pooh!’” our Tommy

cried.

“L’Anglais pour ‘Va!’”

the Frenchman crowed.

And so, with undiminished pride,

Each went on his respective road.

A gentleman of City

fame

Now claims your kind attention;

East India broking was his game,

His name I shall not mention:

No one of finely-pointed sense

Would violate a confidence,

And shall I go

And do it? No!

His name I shall not mention.

p.

73He had a trusty wife and true,

And very cosy quarters,

A manager, a boy or two,

Six clerks, and seven porters.

A broker must be doing well

(As any lunatic can tell)

Who can employ

An active boy,

Six clerks, and seven porters.

His knocker advertised no dun,

No losses made him sulky,

He had one sorrow—only one—

He was extremely bulky.

A man must be, I beg to state,

Exceptionally fortunate

Who owns his chief

And only grief

Is—being very bulky.

“This load,” he’d say,

“I cannot bear;

I’m nineteen stone or twenty!

Henceforward I’ll go in for air

And exercise in plenty.”

Most people think that, should it

come,

They can reduce a bulging tum

To measures fair

By taking air

And exercise in plenty.

p.

74In every weather, every day,

Dry, muddy, wet, or gritty,

He took to dancing all the way

From Brompton to the City.

You do not often get the chance

Of seeing sugar brokers dance

From their abode

In Fulham Road

Through Brompton to the City.

He braved the gay and guileless laugh

Of children with their nusses,

The loud uneducated chaff

Of clerks on omnibuses.

Against all minor things that

rack

A nicely-balanced mind, I’ll

back

The noisy chaff

And ill-bred laugh

Of clerks on omnibuses.

His friends, who heard his money chink,

And saw the house he rented,

And knew his wife, could never think

What made him discontented.

It never entered their pure

minds

That fads are of eccentric

kinds,

Nor would they own

That fat alone

Could make one discontented.

p.

75“Your riches know no kind of pause,

Your trade is fast advancing;

You dance—but not for joy, because

You weep as you are dancing.

To dance implies that man is

glad,

To weep implies that man is

sad;

But here are you

Who do the two—

You weep as you are dancing!”

His mania soon got noised about

And into all the papers;

His size increased beyond a doubt

For all his reckless capers:

It may seem singular to you,

But all his friends admit it

true—

The more he found

His figure round,

The more he cut his capers.

p.

76His bulk increased—no matter that—

He tried the more to toss it—

He never spoke of it as “fat,”

But “adipose deposit.”

Upon my word, it seems to me

Unpardonable vanity

(And worse than that)

To call your fat

An “adipose deposit.”

At length his brawny knees gave way,

And on the carpet sinking,

Upon his shapeless back he lay

And kicked away like winking.

Instead of seeing in his state

The finger of unswerving Fate,

He laboured still

To work his will,

And kicked away like winking.

His friends, disgusted with him now,

Away in silence wended—

p. 77I hardly

like to tell you how

This dreadful story ended.

The shocking sequel to impart,

I must employ the limner’s

art—

If you would know,

This sketch will show

How his exertions ended.

MORAL.

I hate to preach—I hate to

prate—

—I’m no fanatic croaker,

But learn contentment from the fate

Of this East India broker.

He’d everything a man of taste

Could ever want, except a waist;

And discontent

His size anent,

And bootless perseverance blind,

Completely wrecked the peace of mind

Of this East India broker.

Vast empty shell!

Impertinent, preposterous abortion!

With vacant

stare,

And ragged

hair,

And every feature out of all proportion!

Embodiment of echoing inanity!

Excellent type of simpering insanity!

Unwieldy, clumsy nightmare of humanity!

I ring thy

knell!

To-night

thou diest,

Beast that destroy’st my heaven-born identity!

Nine weeks of

nights,

Before the

lights,

Swamped in thine own preposterous nonentity,

I’ve been ill-treated, cursed, and thrashed diurnally,

Credited for the smile you wear externally—

I feel disposed to smash thy face, infernally,

As there thou

liest!

I’ve

been thy brain:

I’ve been the brain that lit thy dull concavity!

The human

race

Invest my

face

With thine expression of unchecked depravity,

p. 79Invested

with a ghastly reciprocity,

I’ve been responsible for thy monstrosity,

I, for thy wanton, blundering ferocity—

But not

again!

’T

is time to toll

Thy knell, and that of follies pantomimical:

A nine

weeks’ run,

And thou hast

done

All thou canst do to make thyself inimical.

Adieu, embodiment of all inanity!

Excellent type of simpering insanity!

Unwieldy, clumsy nightmare of humanity!

Freed is thy

soul!

(The Mask respondeth.)

Oh!

master mine,

Look thou within thee, ere again ill-using me.

Art thou

aware

Of nothing

there

Which might abuse thee, as thou art abusing me?

A brain that mourns thine unredeemed rascality?

A soul that weeps at thy threadbare morality?

Both grieving that their individuality

Is merged in

thine?

O’er unreclaimed suburban clays

Some years ago were hobblin’

An elderly ghost of easy ways,

And an influential goblin.

The ghost was a sombre spectral shape,

A fine old five-act fogy,

The goblin imp, a lithe young ape,

A fine low-comedy bogy.

And as they exercised their joints,

Promoting quick digestion,

They talked on several curious points,

And raised this delicate question:

p.

81“Which of us two is Number One—

The ghostie, or the goblin?”

And o’er the point they raised in fun

They fairly fell a-squabblin’.

They’d barely speak, and each, in

fine,

Grew more and more reflective:

Each thought his own particular line

By chalks the more effective.

At length they settled some one should

By each of them be haunted,

And so arrange that either could

Exert his prowess vaunted.

“The Quaint against the

Statuesque”—

By competition lawful—

The goblin backed the Quaint Grotesque,

The ghost the Grandly Awful.

“Now,” said the goblin, “here’s my

plan—

In attitude commanding,

I see a stalwart Englishman

By yonder tailor’s standing.

“The very fittest man on earth

My influence to try on—

Of gentle, p’r’aps of noble birth,

And dauntless as a lion!

Now wrap yourself within your shroud—

Remain in easy hearing—

Observe—you’ll hear him scream aloud

When I begin appearing!”

p.

82The imp with yell unearthly—wild—

Threw off his dark enclosure:

His dauntless victim looked and smiled

With singular composure.

For hours he tried to daunt the youth,

For days, indeed, but vainly—

The stripling smiled!—to tell the truth,

The stripling smiled inanely.

For weeks the goblin weird and wild,

That noble stripling haunted;

For weeks the stripling stood and smiled,

Unmoved and all undaunted.

The sombre ghost exclaimed, “Your plan

Has failed you, goblin, plainly:

Now watch yon hardy Hieland man,

So stalwart and ungainly.

p.

83“These are the men who chase the roe,

Whose footsteps never falter,

Who bring with them, where’er they go,

A smack of old Sir

Walter.

Of such as he, the men sublime

Who lead their troops victorious,

Whose deeds go down to after-time,

Enshrined in annals glorious!

“Of such as he the bard has said

‘Hech thrawfu’ raltie rorkie!

Wi’ thecht ta’ croonie clapperhead

And fash’ wi’ unco pawkie!’

He’ll faint away when I appear,

Upon his native heather;

Or p’r’aps he’ll only scream with fear,

Or p’r’aps the two together.”

The spectre showed himself, alone,

To do his ghostly battling,

With curdling groan and dismal moan,

And lots of chains a-rattling!

But no—the chiel’s stout Gaelic stuff

Withstood all ghostly harrying;

His fingers closed upon the snuff

Which upwards he was carrying.

For days that ghost declined to stir,

A foggy shapeless giant—

For weeks that splendid officer

Stared back again defiant.

p. 84Just as

the Englishman returned

The goblin’s vulgar staring,

Just so the Scotchman boldly spurned

The ghost’s unmannered scaring.

For several years the ghostly twain

These Britons bold have haunted,

But all their efforts are in vain—

Their victims stand undaunted.

This very day the imp, and ghost,

Whose powers the imp derided,

Stand each at his allotted post—

The bet is undecided.

A Bishop

once—I will not name his see—

Annoyed his clergy in the mode conventional;

From pulpit shackles never set them free,

And found a sin where sin was unintentional.

All pleasures

ended in abuse auricular—

The Bishop was

so terribly particular.

Though, on the whole, a wise and upright

man,

He sought to make of human pleasures clearances;

And form his priests on that much-lauded plan

Which pays undue attention to appearances.

He

couldn’t do good deeds without a psalm in ’em,

Although, in

truth, he bore away the palm in ’em.

Enraged to find a deacon at a dance,

Or catch a curate at some mild frivolity,

He sought by open censure to enhance

Their dread of joining harmless social jollity.

Yet he enjoyed

(a fact of notoriety)

The ordinary

pleasures of society.

p.

86One evening, sitting at a pantomime

(Forbidden treat to those who stood in fear of

him),

Roaring at jokes, sans metre, sense, or rhyme,

He turned, and saw immediately in rear of him,

His peace of

mind upsetting, and annoying it,

A curate, also

heartily enjoying it.

Again, ’t was Christmas Eve, and to

enhance

His children’s pleasure in their harmless

rollicking,

He, like a good old fellow, stood to dance;

When something checked the current of his

frolicking:

That curate,

with a maid he treated lover-ly,

Stood up and

figured with him in the “Coverley!”

Once, yielding to an universal choice

(The company’s demand was an emphatic one,

For the old Bishop had a glorious voice),

In a quartet he joined—an operatic one.

Harmless enough,

though ne’er a word of grace in it,

When, lo! that

curate came and took the bass in it!

One day, when passing through a quiet

street,

He stopped awhile and joined a Punch’s

gathering;

And chuckled more than solemn folk think meet,

To see that gentleman his Judy lathering;

And heard, as

Punch was being treated penalty,

That phantom

curate laughing all hyænally.

p.

87Now at a picnic, ’mid fair golden curls,

Bright eyes, straw hats, bottines that fit

amazingly,

A croquêt-bout is planned by all the girls;

And he, consenting, speaks of croquêt

praisingly;

But suddenly

declines to play at all in it—

The curate fiend

has come to take a ball in it!

Next, when at quiet sea-side village, freed

From cares episcopal and ties monarchical,

He grows his beard, and smokes his fragrant weed,

In manner anything but hierarchical—

He

sees—and fixes an unearthly stare on it—

That

curate’s face, with half a yard of hair on it!

At length he gave a charge, and spake this

word:

“Vicars, your curates to enjoyment urge ye

may;

To check their harmless pleasuring’s absurd;

What laymen do without reproach, my clergy

may.”

He spake, and

lo! at this concluding word of him,

The curate

vanished—no one since has heard of him.

King Borria Bungalee

Boo

Was a man-eating African swell;

His sigh was a hullaballoo,

His whisper a horrible yell—

A horrible, horrible yell!

p.

89Four subjects, and all of them male,

To Borria doubled the

knee,

They were once on a far larger scale,

But he’d eaten the balance, you see

(“Scale” and “balance” is

punning, you see).

There was haughty Pish-Tush-Pooh-Bah,

There was lumbering Doodle-Dum-Dey,

Despairing Alack-A-Dey-Ah,

And good little Tootle-Tum-Teh—

Exemplary Tootle-Tum-Teh.

One day there was grief in the crew,

For they hadn’t a morsel of meat,

And Borria Bungalee Boo

Was dying for something to eat—

“Come, provide me with something to eat!

“Alack-a-Dey,

famished I feel;

Oh, good little Tootle-Tum-Teh,

Where on earth shall I look for a meal?

For I haven’t no dinner to-day!—

Not a morsel of dinner to-day!

“Dear Tootle-Tum, what shall we do?

Come, get us a meal, or, in truth,

If you don’t, we shall have to eat you,

Oh, adorable friend of our youth!

Thou beloved little friend of our youth!”

p.

90And he answered, “Oh, Bungalee

Boo,

For a moment I hope you will wait,—

Tippy-Wippity Tol-the-Rol-Loo

Is the Queen of a neighbouring state—

A remarkably neighbouring state.

“Tippy-Wippity

Tol-the-Rol-Loo,

She would pickle deliciously cold—

And her four pretty Amazons, too,

Are enticing, and not very old—

Twenty-seven is not very old.

“There is neat little Titty-Fol-Leh,

There is rollicking Tral-the-Ral-Lah,

There is jocular Waggety-Weh,

There is musical Doh-Reh-Mi-Fah—

There’s the nightingale Doh-Reh-Mi-Fah!”

So the forces of Bungalee

Boo

Marched forth in a terrible row,

And the ladies who fought for Queen

Loo

Prepared to encounter the foe—

This dreadful, insatiate foe!

But they sharpened no weapons at all,

And they poisoned no arrows—not they!

They made ready to conquer or fall

In a totally different way—

An entirely different way.

p.

91With a crimson and pearly-white dye

They endeavoured to make themselves fair,

With black they encircled each eye,

And with yellow they painted their hair

(It was wool, but they thought it was hair).

And the forces they met in the field:—

And the men of King

Borria said,

“Amazonians, immediately yield!”

And their arrows they drew to the head—

Yes, drew them right up to the head.

But jocular Waggety-Weh

Ogled Doodle-Dum-Dey

(which was wrong),

And neat little Titty-Fol-Leh

Said, “Tootle-Tum,

you go along!

You naughty old dear, go along!”

And rollicking Tral-the-Ral-Lah

Tapped Alack-a-Dey-Ah

with her fan;

And musical Doh-Reh-Mi-Fah

Said, “Pish, go

away, you bad man!

Go away, you delightful young man!”

And the Amazons simpered and sighed,

And they ogled, and giggled, and flushed,

And they opened their pretty eyes wide,

And they chuckled, and flirted, and blushed

(At least, if they could, they’d have

blushed).

p.

92But haughty Pish-Tush-Pooh-Bah

Said, “Alack-a-Dey,

what does this mean?”

And despairing Alack-a-Dey-Ah

Said, “They think us uncommonly green!

Ha! ha! most uncommonly green!”

Even blundering Doodle-Dum-Dey

Was insensible quite to their leers,

And said good little Tootle-Tum-Teh,

“It’s your blood we desire, pretty

dears—

We have come for our dinners, my dears!”

And the Queen of the Amazons fell

To Borria Bungalee

Boo,—

In a mouthful he gulped, with a yell,

Tippy-Wippity

Tol-the-Rol-Loo—

The pretty Queen

Tol-the-Rol-Loo.

And neat little Titty-Fol-Leh

Was eaten by Pish-Pooh-Bah,

And light-hearted Waggety-Weh

By dismal Alack-a-Dey-Ah—

Despairing Alack-a-Dey-Ah.

And rollicking Tral-the-Ral-Lah

Was eaten by Doodle-Dum-Dey,

And musical Doh-Reh-Mi-Fah

By good little Tootle-Dum-Teh—

Exemplary Tootle-Tum-Teh!

Bob Polter was a

navvy, and

His hands were coarse, and dirty too,

His homely face was rough and tanned,

His time of life was thirty-two.

He lived among a working clan

(A wife he hadn’t got at all),

A decent, steady, sober man—

No saint, however—not at all.

p.

94He smoked, but in a modest way,

Because he thought he needed it;

He drank a pot of beer a day,

And sometimes he exceeded it.

At times he’d pass with other men

A loud convivial night or two,

With, very likely, now and then,

On Saturdays, a fight or two.

But still he was a sober soul,

A labour-never-shirking man,

Who paid his way—upon the whole

A decent English working man.

One day, when at the Nelson’s Head

(For which he may be blamed of you),

A holy man appeared, and said,

“Oh, Robert,

I’m ashamed of you.”

He laid his hand on Robert’s beer

Before he could drink up any,

And on the floor, with sigh and tear,

He poured the pot of “thruppenny.”

“Oh, Robert,

at this very bar

A truth you’ll be discovering,

A good and evil genius are

Around your noddle hovering.

p.

95“They both are here to bid you shun

The other one’s society,

For Total Abstinence is one,

The other, Inebriety.”

He waved his hand—a vapour came—

A wizard Polter reckoned

him;

A bogy rose and called his name,

And with his finger beckoned him.

The monster’s salient points to

sum,—

His heavy breath was portery:

His glowing nose suggested rum:

His eyes were gin-and-wortery.

His dress was torn—for dregs of ale

And slops of gin had rusted it;

His pimpled face was wan and pale,

Where filth had not encrusted it.

p.

96“Come, Polter,”

said the fiend, “begin,

And keep the bowl a-flowing on—

A working man needs pints of gin

To keep his clockwork going on.”

Bob shuddered:

“Ah, you’ve made a miss

If you take me for one of you:

You filthy beast, get out of this—

Bob Polter don’t

wan’t none of you.”

The demon gave a drunken shriek,

And crept away in stealthiness,

And lo! instead, a person sleek,

Who seemed to burst with healthiness.

“In me, as your adviser hints,

Of Abstinence you’ve got a type—

Of Mr. Tweedie’s pretty

prints

I am the happy prototype.

“If you abjure the social toast,

And pipes, and such frivolities,

You possibly some day may boast

My prepossessing qualities!”

Bob rubbed his eyes,

and made ’em blink:

“You almost make me tremble, you!

If I abjure fermented drink,

Shall I, indeed, resemble you?

p.

97“And will my whiskers curl so tight?

My cheeks grow smug and muttony?

My face become so red and white?

My coat so blue and buttony?

“Will trousers, such as yours, array

Extremities inferior?

Will chubbiness assert its sway

All over my exterior?

“In this, my unenlightened state,

To work in heavy boots I comes;

Will pumps henceforward decorate

My tiddle toddle tootsicums?

p.

98“And shall I get so plump and fresh,

And look no longer seedily?

My skin will henceforth fit my flesh

So tightly and so Tweedie-ly?”

The phantom said, “You’ll have all

this,

You’ll know no kind of huffiness,

Your life will be one chubby bliss,

One long unruffled puffiness!”

“Be off!” said irritated Bob.

“Why come you here to bother one?

You pharisaical old snob,

You’re wuss almost than t’other one!

“I takes my pipe—I takes my pot,

And drunk I’m never seen to be:

I’m no teetotaller or sot,

And as I am I mean to be!”

Strike the

concertina’s melancholy string!

Blow the spirit-stirring harp like anything!

Let the piano’s martial

blast

Rouse the Echoes of the Past,

For of Agib, Prince of Tartary, I sing!

Of Agib, who, amid

Tartaric scenes,

Wrote a lot of ballet music in his teens:

His gentle spirit rolls

In the melody of souls—

Which is pretty, but I don’t know what it means.

Of Agib, who could

readily, at sight,

Strum a march upon the loud Theodolite.

He would diligently play

On the Zoetrope all day,

And blow the gay Pantechnicon all night.

p.

100One winter—I am shaky in my dates—

Came two starving Tartar minstrels to his gates;

Oh, Allah be obeyed,

How infernally they played!

I remember that they called themselves the

“Oüaits.”

Oh! that day of sorrow, misery, and rage,

I shall carry to the Catacombs of Age,

Photographically lined

On the tablet of my mind,

When a yesterday has faded from its page!

Alas! Prince Agib

went and asked them in;

Gave them beer, and eggs, and sweets, and scent, and tin.

And when (as snobs would say)

They had “put it all

away,”

He requested them to tune up and begin.

Though its icy horror chill you to the core,

I will tell you what I never told before,—

The consequences true

Of that awful interview,

For I listened at the keyhole in the door!

They played him a sonata—let me see!

“Medulla oblongata”—key of G.

Then they began to sing

That extremely lovely thing,

“Scherzando! ma non troppo,

ppp.”

p.

101He gave them money, more than they could count,

Scent from a most ingenious little fount,

More beer, in little kegs,

Many dozen hard-boiled eggs,

And goodies to a fabulous amount.

Now follows the dim horror of my tale,

And I feel I’m growing gradually pale,

For, even at this day,

Though its sting has passed

away,

When I venture to remember it, I quail!

The elder of the brothers gave a squeal,

All-overish it made me for to feel;

“Oh, Prince,” he says, says he,

“If a Prince indeed you

be,

I’ve a mystery I’m going to reveal!

p.

102“Oh, listen, if you’d shun a horrid

death,

To what the gent who’s speaking to you saith:

No ‘Oüaits’ in

truth are we,

As you fancy that we be,

For (ter-remble!) I am Aleck—this is Beth!”

Said Agib,

“Oh! accursed of your kind,

I have heard that ye are men of evil mind!”

Beth

gave a dreadful shriek—

But before he’d time to

speak

I was mercilessly collared from behind.

In number ten or twelve, or even more,

They fastened me full length upon the floor.

On my face extended flat,

I was walloped with a cat

For listening at the keyhole of a door.

p.

103Oh! the horror of that agonizing thrill!

(I can feel the place in frosty weather still).

For a week from ten to four

I was fastened to the floor,

While a mercenary wopped me with a will

They branded me and broke me on a wheel,

And they left me in an hospital to heal;

And, upon my solemn word,

I have never never heard

What those Tartars had determined to reveal.

But that day of sorrow, misery, and rage,

I shall carry to the Catacombs of Age,

Photographically lined

On the tablet of my mind,

When a yesterday has faded from its page

Macphairson Clonglocketty

Angus Mcclan

Was the son of an elderly labouring man;

You’ve guessed him a Scotchman, shrewd reader, at sight,

And p’r’aps altogether, shrewd reader, you’re

right.

From the bonnie blue Forth to the lovely

Deeside,

Round by Dingwall and Wrath to the mouth of the Clyde,

There wasn’t a child or a woman or man

Who could pipe with Clonglocketty Angus

Mcclan.

No other could wake such detestable groans,

With reed and with chaunter—with bag and with drones:

All day and ill night he delighted the chiels

With sniggering pibrochs and jiggety reels.

p.

105He’d clamber a mountain and squat on the

ground,

And the neighbouring maidens would gather around

To list to the pipes and to gaze in his een,

Especially Ellen McJones Aberdeen.

All loved their McClan, save a Sassenach brute,

Who came to the Highlands to fish and to shoot;

He dressed himself up in a Highlander way,

Tho’ his name it was Pattison Corby

Torbay.

Torbay had incurred

a good deal of expense

To make him a Scotchman in every sense;

But this is a matter, you’ll readily own,

That isn’t a question of tailors alone.

A Sassenach chief may be bonily built,

He may purchase a sporran, a bonnet, and kilt;

Stick a skeän in his hose—wear an acre of

stripes—

But he cannot assume an affection for pipes.

Clonglockety’s

pipings all night and all day

Quite frenzied poor Pattison Corby

Torbay;

The girls were amused at his singular spleen,

Especially Ellen McJones Aberdeen,

“Macphairson

Clonglocketty Angus, my lad,

With pibrochs and reels you are driving me mad.

If you really must play on that cursed affair,

My goodness! play something resembling an air.”

p.

106Boiled over the blood of Macphairson McClan—

The Clan of Clonglocketty rose as one man;

For all were enraged at the insult, I ween—

Especially Ellen McJones Aberdeen.

“Let’s show,” said McClan, “to this Sassenach loon

That the bagpipes can play him a regular tune.

Let’s see,” said McClan,

as he thoughtfully sat,

“‘In my Cottage’ is

easy—I’ll practise at that.”

He blew at his “Cottage,” and blew

with a will,

For a year, seven months, and a fortnight, until

(You’ll hardly believe it) McClan, I declare,

Elicited something resembling an air.

p.

107It was wild—it was fitful—as wild as the

breeze—

It wandered about into several keys;

It was jerky, spasmodic, and harsh, I’m aware;

But still it distinctly suggested an air.

The Sassenach screamed, and the Sassenach

danced;

He shrieked in his agony—bellowed and pranced;

And the maidens who gathered rejoiced at the scene—

Especially Ellen McJones Aberdeen.

“Hech gather, hech gather, hech gather

around;

And fill a’ ye lugs wi’ the exquisite sound.

An air fra’ the bagpipes—beat that if ye can!

Hurrah for Clonglocketty Angus

McClan!”

The fame of his piping spread over the land:

Respectable widows proposed for his hand,

And maidens came flocking to sit on the green—

Especially Ellen McJones Aberdeen.

One morning the fidgety Sassenach swore

He’d stand it no longer—he drew his claymore,

And (this was, I think, in extremely bad taste)

Divided Clonglocketty close to the

waist.

Oh! loud were the wailings for Angus McClan,

Oh! deep was the grief for that excellent man;

The maids stood aghast at the horrible scene—

Especially Ellen McJones Aberdeen.

p.

108It sorrowed poor Pattison Corby

Torbay

To find them “take on” in this serious way;

He pitied the poor little fluttering birds,

And solaced their souls with the following words:

“Oh, maidens,” said Pattison, touching his hat,

“Don’t blubber, my dears, for a fellow like that;

Observe, I’m a very superior man,

A much better fellow than Angus

McClan.”

They smiled when he winked and addressed them

as “dears,”

And they all of them vowed, as they dried up their tears,

A pleasanter gentleman never was seen—

Especially Ellen McJones Aberdeen.

Policeman Peter

Forth I drag

From his obscure retreat:

He was a merry genial wag,

Who loved a mad conceit.

If he were asked the time of day,

By country bumpkins green,

He not unfrequently would say,

“A quarter past thirteen.”

If ever you by word of mouth

Inquired of Mister

Forth

The way to somewhere in the South,

He always sent you North.

p. 110With

little boys his beat along

He loved to stop and play;

He loved to send old ladies wrong,

And teach their feet to stray.

He would in frolic moments, when

Such mischief bent upon,

Take Bishops up as betting men—

Bid Ministers move on.

Then all the worthy boys he knew

He regularly licked,

And always collared people who

Had had their pockets picked.

He was not naturally bad,

Or viciously inclined,

But from his early youth he had

A waggish turn of mind.

The Men of London grimly scowled

With indignation wild;

The Men of London gruffly growled,

But Peter calmly

smiled.

Against this minion of the Crown

The swelling murmurs grew—

From Camberwell to Kentish Town—

From Rotherhithe to Kew.

Still humoured he his wagsome turn,

And fed in various ways

The coward rage that dared to burn,

But did not dare to blaze.

p.

111Still, Retribution has her day,

Although her flight is slow:

One day that Crusher lost his way

Near Poland Street, Soho.

The haughty boy, too proud to ask,

To find his way resolved,

And in the tangle of his task

Got more and more involved.

The Men of London, overjoyed,

Came there to jeer their foe,

And flocking crowds completely cloyed

The mazes of Soho.

The news on telegraphic wires

Sped swiftly o’er the lea,

Excursion trains from distant shires

Brought myriads to see.

For weeks he trod his self-made beats

Through Newport- Gerrard- Bear-

Greek- Rupert- Frith- Dean- Poland- Streets,

And into Golden Square.

p. 112But all,

alas! in vain, for when

He tried to learn the way

Of little boys or grown-up men,

They none of them would say.

Their eyes would flash—their teeth would

grind—

Their lips would tightly curl—

They’d say, “Thy way thyself must find,

Thou misdirecting churl!”

And, similarly, also, when

He tried a foreign friend;

Italians answered, “Il balen”—

The French, “No comprehend.”

The Russ would say with gleaming eye

“Sevastopol!” and groan.

The Greek said, “Τυπτω,

τυπτομαι,

Τυπτω,

τυπτειν,

τυπτων.”

p. 113To

wander thus for many a year

That Crusher never ceased—

The Men of London dropped a tear,

Their anger was appeased.

At length exploring gangs were sent

To find poor Forth’s remains—

A handsome grant by Parliament

Was voted for their pains.

To seek the poor policeman out

Bold spirits volunteered,

And when they swore they’d solve the doubt,

The Men of London cheered.

And in a yard, dark, dank, and drear,

They found him, on the floor—

It leads from Richmond Buildings—near

The Royalty stage-door.

With brandy cold and brandy hot

They plied him, starved and wet,

And made him sergeant on the spot—

The Men of London’s pet!

Roll on, thou ball,

roll on!

Through pathless realms of Space

Roll on!

What though I’m in a sorry case?

What though I cannot meet my bills?