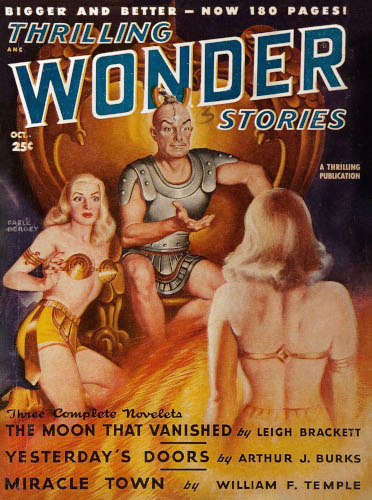

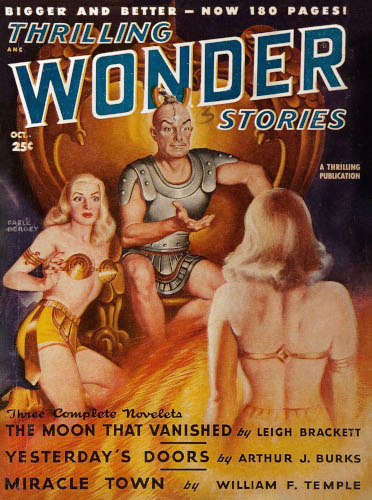

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Yesterday's doors, by Arthur J. Burks

Title: Yesterday's doors

Author: Arthur J. Burks

Release Date: March 9, 2023 [eBook #70251]

Language: English

Produced by: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Thrilling Wonder Stories October 1948.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

CHAPTER I

Lost Memory

It started off like an old story. It happens every day or so in New York City. A man or woman, tired of living, becomes an amnesia victim and loses himself or herself in the crowd. A few stay lost. A few persist in not remembering as long as they can. Many are really amnesiacs.

I didn't know my name, or whether I had one. I didn't know how old I was, though I guessed about forty. I didn't remember the clothes I wore, or my face in the mirror. I had no memory of yesterday or any day, and even the events of just an hour ago slipped away from me. I knew that something was radically wrong.

How wrong it was and how long the condition had lasted I had no way of surmising. I just know I found myself in a dark room, being interrogated like a criminal, by a group of men in uniform. Later I learned that the room was somewhere on Centre Street, in downtown Manhattan. The policemen and men in plainclothes I had never seen before. I never did know their names.

A grizzled man with three yellow stripes on his sleeve struck me with the back of his hand, then the front.

"You deny that your name is Dean Hale? You deny that you killed Marian Slade, cut her body to pieces and pushed them into the sewer?"

"I deny nothing," I said dully, as if I were very tired. "I never heard of Marian Slade. I never heard of Dean Hale. I don't know who I am, or where I came from, or whether I ever cut anybody to pieces or not."

There was a concerted gasp from all present.

"Well, after all these hours, it develops you do have a tongue, and can use it. I thought we'd never hammer anything out of you."

So, for several hours, they had been working on me like this, "hammering" me, as the sergeant had just said—and though I now felt that I had been much abused, I didn't remember so much as one of the blows that had been dealt me. I recite this to indicate the utter depths of my "lostness." A man, even a victim of amnesia, should remember when he has been beaten half to death.

"I don't know anything about myself," I said.

"Now don't go a-trying that amnesia gag on us," said one of the men in plainclothes.

Just then another party entered the darkroom, which was dark everywhere but where I sat under blazing electrics.

"He's not Dean Hale, has no record here at all," said the newcomer. "His prints don't match with Hale's."

All I knew now was that I wasn't somebody named Dean Hale.

"He has to be somebody," said a plainclothes man, "Dean Hale or not—and when we find out who, the fact will also remain that he killed Marian Slade."

How unreal the whole thing was to me. I realized no danger in myself in these accusations. I forgot blows after they had been struck. I think I even forgot to feel the pain of them. Finally my inquisitors gave it up.

"We'll make a check in Missing Persons," someone said.

They didn't find me there, either, though they held me three days while they checked. I forgot the three days, each of them, until long after—until I had the pictures clearly enough in mind that I could set down the facts as I am now doing. The police finally decided I wasn't a murderer, but that I was "missing," actually and mentally, an amnesia victim who could not be aroused. That's where Jan Rober, one of the plainclothes men came in.

"A touch of shock treatment might help you," he told me, visiting me alone and somewhat mysteriously in my cell. "There is a laboratory near Westchester I'm interested in. Modern equipment, far in advance of science. Nobody knows about it. Sometimes I take missing persons there, to help them remember. The surgeons, doctors, scientists there, are my friends."

"They pay you to find people who are lost, for whom no one is likely to inquire, and take them there?" I asked, wondering from what deep well of verbal knowledge I dredged the words, and the fear that inspired them. Jan Rober's eyes narrowed.

"You're accusing me of something?" he said softly.

"I don't know," I said, "but it just occurred to me that medical and surgical science is often hampered because it can't work with human beings, though how this occurs to me I don't know. Assembling missing persons, orphans, people in whom nobody has the slightest interest, whose eternal disappearance would cause no questioning, would be a boon to such scientists, and a source of revenue to whoever provided them with human guinea pigs."

"For an amnesiac," he said, "your thinking is to the point."

"But I'd just as soon be dead and buried as to know nothing of myself," I went on. "I find I don't care overly much. But do you believe that I may somehow be shocked out of amnesia? Don't forget, a lot of heavy hands have been laid on me in the last few days—if what you've just told me is true—and the hands haven't shocked me into remembering."

"There are shocks, and shocks," he said. "Ever hear of the atom bomb? Know anything about electrons? Ever hear of a cyclotron? Part of the work of my friends is in the field of nuclear fission, which means less to me than it does to you; though just between us, if you aren't a surgeon—from your fingers—I never saw one. Besides, the gent who cut up Marian Slade knew his surgery."

That gave me a little chill. Was I a surgeon? Had I slain some woman named Marian Slade? Was I innately capable of cutting a human body to bits and pushing the pieces into the sewer? I didn't know!

"If I did anything like that, Rober," I said, "then if your friends cut me into little pieces, I have merely paid off for Marian Slade."

"And escaped the electric chair!" said Rober drily. "Also, your memory is better than it was: you remember my name, and I told it to you once, when I came in. Well, you're going to be released in my custody in an hour or so. If you care to trust me, we'll visit The Lab."

The Lab! That's all it was ever called, if memory serves me, and memory does serve me now. The Lab! Nobody, once having experienced a little segment of it, could possibly ever again have forgotten it.

It wasn't much to look at, from the outside; just a squatty, large, square building of gray granite, in the midst of a clearing in Westchester's wooded area. It was wired like a prison, and there were signs warning people away. There were also people standing guard. The Lab was either a prison or a sanitarium—but not once while I was there did I see anybody in the place who could conceivably have been a convict or a patient. I saw only the doctors, the surgeons, if such they were, the scientists, and Marian Slade!

Yes, Marian Slade was the name of the nurse, and she was about the prettiest young woman—too young for me, in fact—I had ever seen. When I was introduced to her, I said:

"Oh, yes, Dean Hale murdered you, cut you into small pieces, and thrust you into a sewer."

Her face was impassive, her eyes did not flicker or show alarm. She only said, quite calmly,

"Yes, Mr. Hale, I remember every detail. Now, be good enough to follow me."

I was being treated like a maniac who might become violent. This nurse, with the name of a murdered woman, was coddling me, treating me gently, so I wouldn't erupt! Jan Rober left me with her and was gone, and in my imagination I could hear the rustling of bills of large denomination. I never expected to get out alive. I didn't much care.

Marian Slade took me to a room, told me what to do with the roomy garments she gave me. I found myself, shortly, in a kind of nightshirt, standing on the threshold of a room of gadgets. Yes, I must be a doctor, or some sort of scientist, for I recognized many of the gadgets there. This room was an up-to-date surgery. It had everything.

It had everything including the pygmy cyclotron, set in the mathematical center of the room. Marian Slade didn't introduce the men in white to me. I was never to know their names. She told them I was Dean Hale though Jan Rober must have told her I wasn't. She needed a handle by which to identify me, and the police had called me that for days.

I wondered idly how Jan Rober would explain my "escape" to his colleagues, unless all of them were in league with The Lab to produce "willful missin's."

In the room were great oxygen tanks, trays behind glass filled with surgical instruments, operating tables, X-Ray machines, a fluoroscope, pale screens against a far wall—screens against which, well, just what sort of strange pictures might not be shown?

My eyes kept returning to the cyclotron. It fascinated me. If it worked it was a masterly thing. Cyclotrons took up a building in themselves. How did I know that? The question flashed through my mind, and the answer, if any had been hovering on the verge of my consciousness, vanished into the general blur of all my yesterdays, my passing hours.

Near the cyclotron, if that's what it was, were twelve chairs, above which were metal globes, or hoods, like hair dryers, the chairs set in a kind of semi-circle around three sides of the cyclotron. Each chair was just the right size to hold a human body.

I glanced past the chairs—nobody had yet asked me to sit down, and Marian Slade had disappeared somewhere behind me—and spotted the electric panel for the first time. But another minute passed, a minute during which the profound scrutiny of the "scientists" became deeper, more profound, before I connected the electric panel with the chairs.

Those seats arranged around the cyclotron were electric chairs! Each chair would be filled with a human being, and all could be electrocuted at one time, and if all were "vanishers," who would care?

"Gentlemen," I said, "you might ask me to be seated! Just which of the electric chairs has been assigned to me?"

There was a stir among the twelve men who had ranged themselves around the great room to await my coming. One of them, the eldest, now that I had discovered they were not dummies, but living men, bowed to me gravely and said:

"Welcome to the Lab, Mr. Hale, if that is your name. Allow me to introduce you to my colleagues. You will understand, later on, our reasons for failing to furnish correct names. I am Doctor A."

Then he gave me the initials of the others, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K and L. I never knew them by anything else. They varied in appearance as men usually do, and their ages ran from perhaps twenty-five to seventy-five, Doctor A being obviously the eldest and the dean of the Lab.

Even the fact that all were men in white did not serve to hide their differences. Their eyes were unusual, all of them. I think they held a coldness, a searching hard coldness, in common. They were men of science, by their appearance, and they were ruled by science.

Each would have given his life for science, if by so doing he did not slow the progress of science instead of advancing it. That is, he would have given his life if he had not realized that his death would be a great loss to his chosen field. By the same token, not one of them regarded the life of any individual as being important enough to fuss much about. Understand this is only my personal opinion, the personal opinion of a man lost in the utter depths of amnesia.

Those twelve men, however, struck me forcibly, short men, thin, fat, tall, so that the urge was on me to make sketches of them. Just why, I did not know, never having made a sketch of anyone I could remember, never before having desired to sketch any one. Perhaps I should have told some of them of this urge. Maybe it would have helped in backtracking, identifying me. But perhaps they did not wish me to be further identified.

"You have lost your memory," said Doctor A. "You have been brought here to recall your yesterdays. There is some danger to you in this shock treatment though we take every precaution known to science. Do you wish to know yourself strongly enough to take the risk, and to absolve us therefrom? To take your place in a chair by your own free will?"

"If I do not, Doctor A," I said, "isn't it true that I will placed in the selected chair forcibly?"

"Mr. Hale," said Doctor A, "you are at liberty to leave. Nurse Slade will escort you to the door of the Lab, and you may go where you wish. You may even return to your home and report everything that has happened to you here."

Dr. A's words aroused my resentment. Here I was, lost, and he talked of home!

"My home!" I said, bitterly. "And just where is my home? Look, Doc, the ordinary ways of restoring the amnesiac have been tried on me without success. This seems my only out. I've been doubtful, because there have been so many strange things connected with it. I was accused, for example, of murdering Marian Slade, cutting her to pieces and thrusting the pieces into a sewer. Yet when I arrive at The Lab I am met by none other than Nurse Marian Slade. You must admit that this could be disturbing."

The doctors let out a concerted sigh. I moved forward as Doctor A bent slightly, his eyes indicating the chairs. As I moved he came to meet and escort me, while the other eleven "scientists" closed in, with something akin to threat in their advance. If a man were not mentally ill when he came to these people, he soon might well be ill. Naturally, I doubted my own sanity. Maybe none of this actually existed save in my addled, lost brain.

I climbed into the central chair. To my amazement the eleven scientists took the other chairs, while Doctor A stood between me and the cyclotron to conduct the experiment, or whatever was to be conducted. The other doctors began to strap themselves into their chairs, as I was being strapped into mine by Doctor A. I realized that, through the use of the atom-smasher, the cyclotron, eleven scientists were somehow going to share whatever was due to happen to me.

Just before Doctor A lowered and adjusted the metal hood over my head, I saw eleven pairs of hands raise up, as women lift their hands to adjust their hats, and pull down eleven hoods to hide their varied faces.

Doctor A fumbled with me, attaching electrodes exactly as if I were going to be electrocuted. Whether the other men there were so wired I did not know, but why else would they have stepped under the hoods, sat in the eleven chairs?

The soft voice of Doctor A came to me as from a great distance, with eerie tones in it caused by the natural amplifier over my head.

"Are you ready, gentlemen?"

There was a chorus of "ayes" from the eleven.

"Mr. Hale?" continued the soft voice.

"Yes, Doctor, I am as ready as I ever expect to be."

CHAPTER II

The First Door

Abruptly there was nothingness, black, impenetrable. Abruptly there was change. Abruptly I stood at the far end of a concrete sidewalk which led across a clearing of beautiful, exquisitely green grass, closely mowed. Afar to right and left dense forest formed an amphitheater for the building at the end of the sidewalk opposite me, and perhaps a hundred yards away.

At first I thought it was the Lab, but only for the briefest seconds. Doctor A's voice had somehow followed me into this great transition, for it said:

"Go ahead, Mr. Hale, hesitate not anywhere. Remember! Be sure to remember. I command you to remember!"

"My name is not Hale," I told him, as I stared at the building at the far end of the strip of sidewalk, the only strip of sidewalk on that lawn of green. "I am Father Wulstan."

Now, just how did it happen that I called myself Father Wulstan? I hadn't the slightest idea then, but only that I was Father Wulstan. But who Father Wulstan was I hadn't the slightest idea. I could not see his habit upon myself, because I still wore the nightshirt.

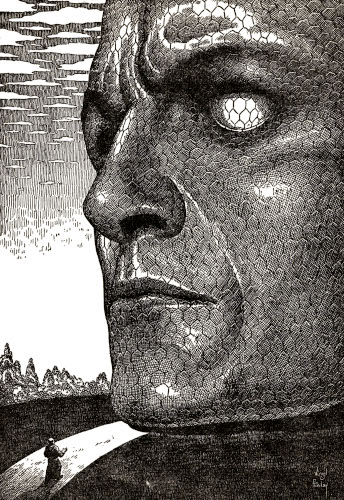

The shape of the building yonder was most unusual and strange. But it was familiar, fearfully familiar. It was shaped like a huge human head. The skull was bald, glistening in the sun with great brilliance, as if the sun itself nestled on the cranium.

But why the familiarity, when I could never have seen this building, or any like it, in all of my life? I asked myself these questions as I strode swiftly toward the "mouth," the front of the building. After all, how did I know I'd never before seen such a building, when I could not remember my yesterdays?

Swiftly I strode along the path, toward the strange Building of the Skull.

I was close enough that the facade of the strange building was beginning to lose its details, to become a smoothly rounded front, when I understood why the Building of the Skull looked so familiar.

The building's facade was my own face!

The skull was my skull, vastly magnified!

Whoever had erected this weird building had most certainly used my skull, or the skull of a twin of mine, as his model!

I had scarcely absorbed this utterly fantastic thought than I realized something else, something that I could not have seen until I lost the outer, apparent detail of the Building of the Skull, by coming close enough to see smaller, more intimate details. Then I made my second, most amazing discovery. The Building of the Skull was walled, roofed and domed, by an infinite mosaic of tiny hexagonal doors! They were doors of a strange shining metal which something inside told me was far more precious than gold.

There was a tiny lock in each door, in each lock a tiny key, and the voice of Doctor A, calm, sure, unexcited, came again to direct me.

"Choose the proper key, Father Wulstan. You know which one it is!"

My hand went unerringly to one of the tiny gray keys in one of the tiny gray doors. My thumb and forefinger turned the key without difficulty, as if the key and the lock were forever freshly oiled. It made no sound.

As the little door opened, there was the sensation of speed, but not of crossing a threshold. Memory came rushing back, so swiftly that I, Father Wulstan, did not even know that I had forgotten anything. The place was the crypt of Saint Dennis, far under the church, deep in the bowels of the earth. The country was England. The time was midnight or thereabouts. The day was Thursday. The year was 792 A.D. Nothing in the mind of Father Wulstan, at this time, considered the year 1947, because it had not yet come.

There were three other priests with me, all older than I. They were very old. I was thirty. I was devout, God loving, almost a religious fanatic. But I loved mankind, too, wished to do for him all that the Master had intended. I was the keeper of the faith, the doer of works. The others were Fathers Dennis, Paul and Elihu.

In both my hands I held an intricate model of dried clay. It was a model of something I had seen many times in dreams. It was a conveyance, a conveyance like none known hitherto in the history of the world, in any history I had ever read or heard of. It certainly was not mentioned in Holy Writ, unless that certain passage in the Revelation of Saint John the Divine were this—wherein he spoke of "flying things out of The Pit."

This conveyance, I realized, complete in every detail save the power by which it might travel, was intended to travel in the air, at any height, like a bird—like the fastest bird known to nature. I had shaped this thing with my loving hands. Its details had come to me in a series of dreams. It had wings of an especially beautiful design. I had burnished the gray of the clay so that it shone, for I had visioned the sun gleaming on those wings.

I had seen this "metal bird" in dreams.

Below the wings was the body of my artificial "bird," and under that body were two wheels. The wheels flared slightly outward, and were joined to the body by straight staves—and herein was I thrice puzzled. In my dream the outer rims of the wheels had been soft, pliable, so that on the ground the "bird" traveled without bouncing. I knew that the staves were of metal, but while I had seen it often in dreams, I had never seen its name.

I felt sure that man had not yet found the metal needed for the wings of my "metal bird." There was something else about it: there were three vents, carefully spaced, under each of the two wings. What traveled through those vents I did not know. I had a "metal bird" which I knew would fly, because I had constructed it again, several times, in wood and paper. Alone in the woods about Saint Dennis, I had flung the model into the air, and it had flown. I had then destroyed my models of wood and paste and paper. I did not know why.

But one thing I did know: if my metal bird did not yet possess the will to fly, if it were as man had been before God breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, so that he became a living soul, then the world was not ready for my metal bird. Yet, if the world were not ready, why had I, a priest of God, dreamed of the metal bird, and finally, made of it a thing of clay only because proper metals, proper gums for the wheels, and proper motive power, were not yet available? I was a true priest, religiously descended from Peter the Rock, against which, as the foundation of the Church, "all Hell might not prevail."

"It is the work of the devil!" said Father Dennis, who had taken the name of this church for which all of us labored. "It should be destroyed."

I studied the face of the saintly old priest, who had done so much for humanity in the sixty-odd years of his priesthood. The face was familiar, for I had known him all the days of my own ministry.

"It is not the work of the devil, Father," I said softly. "It is the work of man, of myself, Father Wulstan of Saint Dennis. I based it on a dream, as did Saint John the Divine, who also saw winged chariots on Patmos."

"You, my son," Father Dennis pointed out, "are not Saint John the Divine, for all your piety. I say the thing should be destroyed."

"But it has been agreed, since I told you of this model, and showed it to you three as the oldest and wisest of all the brethren of Saint Dennis, that we should not give it to science, but should hide it away secretly, here in the crypt of Saint Dennis. Then, what becomes of it in course of time, is in the Hands of God. Who sent me the dream!"

I disliked even that much concession, but they were wise in religion, and I would not stand against them. My greatest desire was not to hide the trim, sleek model away, but to give it to science and beg of science to find the motive power and the missing metals. I would then pray that the Father work closely with science—provided the world was ready for what this dream might give it.

However, here was the climax. I was, besides being a priest, like many another priest, I did things that were not of the ministry. I invented things, dreamed of things that would make earthly life easier for my people. Some priests invented rare wines. Some copied the sacred books in colored inks, spending all their lives to attain written perfection. Some priests studied the stars and came by rare secrets, some of which the church called heresy, some of whom died because of their heresy. I did not believe that was heresy, or that the priests should have died. For myself I believed in earthly as well as spiritual progress.

For that reason I invented things for busy women, for laboring men, for growing children. I invented blocks with letters on them, that could be piled together. Countless other things I brought into the waking state out of my dreams, and made them real. Countless things I assembled while I was awake, between times of busy, devout ministering in my church, the ancient, venerable Saint Dennis.

To bury this model made me feel guilty. Yet my belief in the future of man was such that I knew somewhere up there ahead, generations perhaps, the missing elements of my dream for this model, would be "discovered." That was the reason I agreed to hide the model "metal bird." How and when, if ever, would it be found? Without faith I could not have endured the emptiness of the obvious answer—that eventually, in course of time, Saint Dennis would crumble into ruins, raining those ruins down upon the crypt, burying it for all time from the sight of men, losing to men the thing I had brought into being from my dream inspired.

Other things I had shaped, invented, had come into human use, had bettered the living of mankind. Why should this "metal bird" be an exception?

So, we made a niche for the metal bird in solid rock, a niche which was itself a kind of chapel, just big enough to take the spread wings of the metal bird. I looked at the six vents under the clay wings, and the wheels and staves from which essential elements were missing, and wondered if ever inventive man, in all his generations, had ever left so much to faith in God, and man's future?

We blocked the small "chapel" with a rectangle of stone, and cemented it tightly. I marked the Cross and date upon it in red paint, and blessed myself and my fellow priests before we left the crypt. I was sick at heart, but knew we had done rightly. Two of the three priests had agreed with me that at the very least it could do no harm to preserve the clay model of the metal bird.

As we left the crypt, the flames of guttering candles highlighted the faces of Dennis, Paul and Elihu. They were, as I have said, saintly faces. There was also, I felt, a coldness, a hardness in them, that reminded me of something—something far past, a memory so far back it eluded me entirely. The bodies, the faces, the vestments, were those of the church. The eyes were the eyes of those who sought truth otherwheres than in the church, the eyes of scientists.

I felt the urge to make sketches of their faces. I often did this, and they enjoyed posing.

"I'd like, Father Dennis, Father Paul, Father Elihu," I said, "to make sketches of each of you and the three of you together. I wish I had thought in time. I would have made the sketch and left it behind the rectangle of stone, with my metal bird of dreams."

Father Dennis crossed himself.

"I am glad my likeness does not repose anywhere with this devil's work we have imprisoned behind the red cross! But," and he smiled, "I do not mind another sketch. You have something new in each sketch you make of me!"

So they posed, and I made a sketch of each of them, and of the three together. Then Father Paul brought me a reflecting glass—of a special design I had created for our use in the church of Saint Dennis—and I looked at myself in it, and sketched myself among these three brethren of the church of Saint Dennis. Then I made an end for a little time.

CHAPTER III

Far Retrospect

When we had made an end of sketching—out on the grounds of Saint Dennis, during a period of rest and meditation—we separated and returned to our cells. As I walked back to my cell which was also my workshop, many other priests met me, spoke my name, Father Wulstan, and asked for my blessing. I was a priest with a future in the church, in the world. I was a man of importance as a man as well as a priest.

I remembered the faces of those who met and were blessed by me, there on the grounds and in the austere halls of Saint Dennis, and when I reached my cell-workshop, I made sketches of each of them. Like the first three, Fathers Dennis, Paul and Elihu, there was a familiarity about them that did not stem from daily acquaintance, but from something else, from some elder world, or older time.

I did not understand it, or anything about it, except that the urge to make the sketches was as strong as the urge had always been since the dream, to complete the metal bird model. Such urges, I had always been sure, came from God. Thus I explained my urges, which I never allowed at any time to interfere with the manifold duties of my ministry.

It was a beautiful setting, rural England in 792 A.D., and the church of Saint Dennis one of the saintliest in the land. Many saintly priests, many advanced spirits, came to Saint Dennis for what we could teach them there—and there were many who were taught earthly things by me in my workshop. In some way my fame as a builder of things had traveled in Christendom, so that others wished to know.

When the devotions of the day were over, and it was time to sleep, I lay back on my rough cot with a sigh, fell intently to sleep. No sooner had today, and England, and Saint Dennis' church, vanished from my conscious memory, than a terrifying variation of my dream of the metal bird descended upon me.

I was inside the metal bird, and it was more than large enough to hold me, and the metal bird was flying at vast, awesome speed, speed that was as the speed of spirit, or of sound. Yes, I knew the speed of sound, and of light. The metal bird did not travel with the speed of light but it did travel faster than sound, for far behind me as I flew, with my hands fast on the odd instruments which guided the bird, I heard an awesome noise. It pursued me.

"Now I understand that if I had traveled faster than sound, the sound would never have reached my ears, but I heard it anyway and allowed a little for the oddity, the inconsistencies of dreams, as I trusted others would also make allowances."

I flew far above the earth, and was terrified, so that I pointed the bill of the metal bird downward, to return me to earth as quickly and safely as possible. I aimed the bill at the gleaming brightness of a doomed building that looked to be a cathedral, though shaped somewhat like a skull. It seemed to be all windows, and on each window—all were small—the light of the sun was reflected. Surely even I could make my way to a spot so bright with God's sunlight.

When I aimed the bill of the metal bird at the "cathedral" however, I found I could not swerve it again. I saw that I was going to plunge into that Golgothic building, at this vast speed I was making. That it would destroy me I knew, but that did not seem to matter as much as the sure knowledge that it would also destroy the metal bird which thus would be lost to mankind forever.

I crashed through the building, and felt no pain. I hurtled completely through the Building of the Skull, heard the crashing about me of the destruction I wrought with the body of my metal bird. I passed through the building, emerged into the open again, low above the ground, and saw another building flashing to meet me for further destruction.

It was a rectangular building of gray stone, granite I thought, and there was a kind of fence around it, of metal I did not know. There were men in garments strange to me, guarding the place by their behavior, against attackers. Or else it was a prison, and the guards were there to see that no prisoners escaped.

I passed over the fence, crashed into the squat building, like none I had ever even dreamed of before.

This time there was no emergence. Only the crash, and silence, and utter darkness. In the darkness I felt hands upon me, shaking me, and so, shortly, I came out of the darkness, and found myself facing Doctor A. His face was alight with excitement which he seemed scarcely able to contain. I sat in my electric chair, feeling none the worse for my strange transition into the unknown. The hood no longer hid my head, the electrodes had been removed—if electrodes they were.

The other eleven scientists were assembled about Doctor A, and they were as excited as he was. One thing struck me instantly as I remembered Saint Dennis, for I did remember it now, in every detail. The faces I had sketched in Saint Dennis were all represented right here in The Lab, in the faces of these scientists. Was that why they were all so excited? But of course they could not know what I had experienced, unless they had participated in it. Maybe, by the magic of the diminutive cyclotron, they had done exactly that.

"Just how long," I asked, "have I been away from you delightful gentlemen?"

"You've been sitting in that chair for twelve hours, Hale," said Doctor A. "And during that time you may well have altered the course of military progress in the world. Have you any idea what you've been doing? Do you remember, as I commanded you to remember?"

"Father Wulstan," I said slowly. "I was Father Wulstan. There were other priests, three in particular. I remember: Fathers Dennis, Paul and Elihu." I grinned. "Father Dennis was your twin, Doctor A, as Paul and Elihu were twins of Doctors D and F."

"Look at this," said Doctor A, thrusting a sketch into my hands. "Tell me what it is!"

"A sketch," I said. "By Father Wulstan, of the church of Saint Dennis."

"Which church has been lost to the world for ten centuries!" said Doctor A. "We've checked on it since you began telling us what you were doing. A great church stood on the site in the Fifteen Hundreds, but it was destroyed, and though religious antiquarians believed there was another church below it, and below that a crypt, the lost crypt of Saint Dennis, it was not proved to be a fact until yesterday. We've been in contact with the archeologists who have been excavating for several years on the site—in contact by telephone. They have found the crypt, thanks to questions I asked you while you were away, Hale. Now take a look at this."

He showed me a sketch, of which "Father Wulstan" must have made hundreds, of Father Wulstan's "metal bird." His excitement was greater than ever it had been.

"We have made photostats of it, basing details on your sketch, made right here while you were away, and flown them to Washington, to the Bureau of Aeronautics. Jan Rober took them. This is a jet plane, far in advance of anything aviation has had to date. It is faster than sound. It will pass easily through the wall of compressibility and will not go out of control. The design has been given to the nation, and shortly there will be a practical, full sized jet plane, as here specified."

I began to sink into myself, to feel a horrible depression.

"Then this is all folderol," I said. "I make sketches of priests who have the faces of Doctors A, D, F and perhaps L, only because those faces impressed themselves on me at the moment I went away. And the fact that I have designed, on paper, a jet plane that promises to be faster than any yet made, what does that prove? That I, perhaps, this nameless one whom the police called Dean Hale, whom I called Father Wulstan in my unconsciousness—or whatever the state was which that cyclotron induced—was an architect or a plane designer. All that I need to find out now, is what plane designer has been missing for how long!"

"Not so fast, Hale," said Doctor A, not one iota of his excitement dissipating under the words of my disappointment. "For there is something else you must know."

"Yes, what?"

"In the crypt of Saint Dennis a red painted cross was found on a rectangle of stone set into the solid rock. The stone was removed, and what do you suppose was found behind it?"

I grinned wryly as I answered, excitement mounting in me in spite of myself:

"A tiny hangar, just big enough for a clay model of a metal bird."

"Right! A model airplane done in clay. From the description we had over the telephone, it followed your specifications which we have just given to the Bureau of Aeronautics, exactly, to the letter."

"A hoax!" I said. "A gag!"

"There was a date on the stone hangar," said Doctor A. "The date was Seven-Ninety-Two, A.D.!"

"That could be a gag, too," I insisted, though by now I didn't believe it myself. "It could have been put there by pranksters at any time."

Doctor A gave me a keen glance and then shook his head.

"The crypt of Saint Dennis has been lost to the world for centuries," he said softly. "That's a proved fact. Even if the prank as you call it, was brought about, that metal bird of yours was tucked away in the crypt before fifteen hundred A.D. at which time, if records serve, the world did not use the airplane, especially the jet plane."

"Then," I said, feeling the awe my voice must have expressed, "I, whom you call Dean Hale, and Father Wulstan, are one and the same person. If true, reincarnation is a fact. What does that mean, after twelve hundred years?"

"The answer to that question is the answer to why The Lab was first established, Hale. You wished to remember. You are remembering."

"I'm remembering a lot I didn't bargain for," I said. "Dean Hale is Father Wulstan, or was, and Father Wulstan is now Dean Hale. Now, if you'll just tell me who Dean Hale is, I'll be satisfied!"

"Dean Hale," said Doctor A, "whoever he may turn out to be, is the total of all his past. If reincarnation is true, he has lived countless lives, many useless, many evil, many good. Thus have all men lived, if reincarnation is true. If it is, and we prove it, we as scientists are interested only in your past scientific lives."

"You mean you want me to go through more Father Wulstan stuff?" I demanded.

"You've already remembered Father Wulstan," said Doctor A, "and we are interested only in your past lives which contributed to human progress. There'll be many lives that will remain closed books to you, and to us."

"How many do I re-live?" I asked groaning. "Or even the good ones, if any there were, how many must I re-live?"

"Who knows?" asked Doctor A. "How many profitable doors are there in the walls, dome and roof of the House of the Skull?"

One thing I insisted on, before I went "back" again. I didn't go for the name of Dean Hale, if Hale were a murderer.

"Then we'll call you Everyman," said Doctor A, "since every man, in this same situation, would bring us about the same story, if his proper past lives were chosen. You are Adam Everyman. Now let's get on with the next excursion."

CHAPTER IV

Faster Than Sound

I knew that the eleven scientists who traveled with me, collaborated to build, through the mediation of the cyclotron, the House of the Skull; that it was an enlargement of my own skull. The "doors" were segments, the "keys" symbols of location and identification. The Lab had seemingly proved reincarnation. Could it have been coincidence?

No, I believed I had been Father Wulstan, was still Father Wulstan in spirit, though in this life I had now forgotten, I may have refused to be a minister again. I could understand my refusal in terms of reincarnation. I had once refused, or been compelled to refuse, to do everything required of a scientist. I had hidden a most important invention away. Now I must produce it, in accordance with the Law of Consequences, of Cause and Effect.

The combined thought of the eleven colleagues of Doctor A, directed into the cyclotron, therein to assemble, by the power of thought, special hordes of electrons, could very well construct of them the Building of the Skull, which thus might not be a thought form at all—scientifically! I knew there were things in the invisible man knew, could not prove or delineate; modern experiments with nuclear fission was proving that, and this was somehow nuclear fission far in advance of modern science, according to Jan Rober. Thought could be registered. That fact had long been accepted. Mechanical means could register the weight and substance of thought. Everything that existed, even energy, and therefore thought, was composed of electrons.

I was beginning to see the deep meaning behind The Lab. From my brain alone, the scientists could recover from the Invisible Records, more of world history than could be found in books. If men had existed through endless lives, man the individual had—and I was merely one. Each was an historical record himself.

Thus The Lab seemed to have proved in its work with me. However, I did not believe it. There was no scientific authority for reincarnation, and not even the cleverest of the esoterics could prove it.

Yet, here was the Building of the Skull, tangible, for I touched it with my hands, with the hands of my body, not with astral hands. I turned a certain key in a certain door I seemed to know....

And my name was Anghor, and I had forgotten either key or door, for the simple reason that when I regained "Anghor" I was actually the Anghor who had been—twelve thousand years ago! I was Anghor who had lived, and come to a catastrophic end, though at that moment Anghor did not seem to fear the end, ten thousand years before the Christian era.

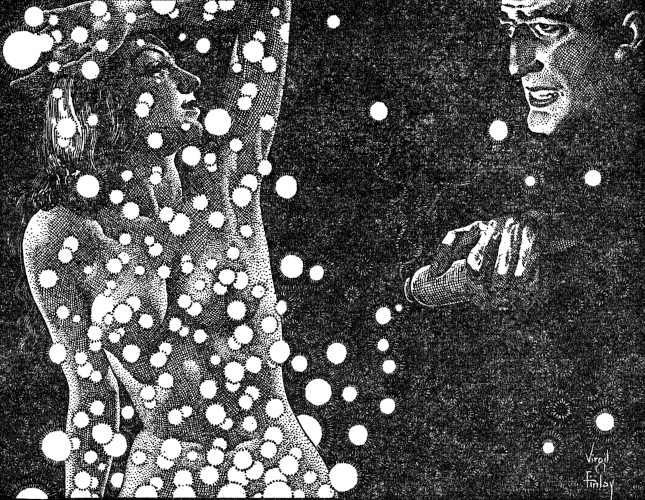

I was Anghor of Atlantis, a sage, a wise man, a scientist, with all the secrets of the universe at my finger tips, and in my brain. I was thirty years old. I was cold, merciless, exacting. My science was exact science. I could even, if allowed by The Masters of Atlantis, my only superiors, have used the Creative Fiat used in The Beginning, and caused my thought forms, the thought forms of anyone, to live, to breathe, to be! But the Masters had taken the right to use the Creative Fiat away from everyone, including myself, because the majority of Atlanteans had misused it.

One thing I knew which stood out above all others: mankind was responsible for everything that happened to himself, even apparently natural catastrophes. The people of Atlantis, for instance, were responsible for the Creeping Mist. It was vile, slimy, almost lethal, like the thoughts of so many who had turned their backs on the teachings and warnings of The Masters. The Creeping Mist, for ten years now, had hidden the sun from Atlantis. We knew the sun was there, of course, but it never shone through, save when one went to the top of The Sun Tower, above the Creeping Mist, to observe it. This privilege had been denied me, now, for those ten years.

I was responsible, because of my radical scientific teachings, for the thoughts of the people; therefore I was responsible for The Creeping Mist. I had been shut away behind the walls of The Laboratory, in the City of the Sun, until I should have found the means of dissipating the Creeping Mist. With the Creative Fiat I could have transmuted it into rain, perhaps, for Atlantean crops; but remember, the Fiat was denied me.

In Atlantis of just before the Catastrophe, mind had reached its apex. Man had never before in world's history, even in Mu, Lemuria or Pan, advanced quite so far in his use of mind. We still used words with which to express ourselves generally, though a minority of us could communicate directly from brain to brain by thought; but even the lowliest, mentally, of us, had the power to Visualize. In other words, when a man used the Atlantean word for river, he made it clear just what river he had in mind, so that his hearers would not think, one of the River Sian, one of the River Ogra, a third of the River Linu, thus receiving his thought in a blurred way.

How was this done? By thought projection. On a televisor, produced by personal thought, beside the skull of the "speaker," appeared an exact replica, a picture, of the very stretch of the River Sian which the speaker had in mind. In effect, this was an adaptation of the Creative Fiat, but so was everything a man did with his brain or with his hands. The only difference was that the Creative Fiat was limitless, every adaptation of it limited, because man had limited himself by his doubts of his own ability.

I myself had invented the Televisor of Speech-Thought. Every Atlantean, even the subjugated, possessed one. It never deteriorated, because I made it of the secret metal which does not rust, tarnish, or decrease. It fitted, as a dental bridge, in the space from which the useless wisdom tooth was invariably removed from all Atlanteans as soon as possible after birth. At the will of the speaker its rays formed the Televisor, and on the Televisor the speaker wrote with his mind the picture he saw when he spoke.

We had other things. The Tor-Dox was one. It was the door which compressed space. There were many such doors, all adjustable. Many miles and many hours separated Sian from Ogra by medieval methods of transportation, but you could step into the Tor-Dox at Sian, first adjusting for destination, and you were instantly in Ogra. I had not made Tor-Dox. My father had, for he, too, possessed the secrets of the past.

Other things we knew and accepted as commonplace. We could, individually, live as long as we wished, remaining perennially young—or we could place ourselves in the hands of the Masters, to live as long or as briefly as they wished; but we had free will.

And that free will was the disastrous inspiration behind the Creeping Mist.

We had been warned by one of the Masters, ten years before, of the Creeping Mist. By now, ten years after, it should have been called the Mounting Mist which hid the light of the sun, save as the dull glow of it came through to blister tender skin and fill the heart with growing terror.

"You are facing destruction, people of Atlantis," the Supreme Master had said, standing on a tall white pillar in the central square of Sian, "if you do not use natural laws as they were given you to use them. Disobey the laws continually, and they will destroy you, surely as the sun rises. Ages ago, the Masters of that time disclosed to some of you all the secrets which science should discover bit by bit, as the people become ready for each discovery.

"The secrets, all the secrets, of the universe, were given to a few—a few who had proved themselves worthy of trust. The Masters erred, as even Masters sometimes may. Some of those who received the secrets in trust, realized the vast power thus given them, and began to use them for their personal needs, and in so doing, subjugated countless of their fellows.

"With each age of progress of the human mind, Masters have warned you, as they warned the people of Mu, of Lemuria, of Pan. They made it clear to Atlanteans then exactly why Mu, Lemuria and Pan sank under the sea—and that Atlantis herself was doomed to the same fate if she did not reform, return to the proper use of natural law! Some heeded, some did not. It is ever the way.

"Those who cry out, those who warn men against themselves, are never thanked, are usually regarded as fanatics, as cranks without knowledge. Beware, the time is set. It will come in ten years, if drastic return to the law is not made by all the people."

So the Supreme Master of Sian had spoken, ten years ago, almost, when he had wrapped his white glowing garment about him and was lowered into the pillar, to vanish since then from sight of all save the Masters, of Whom He was One.

Now, the ten years were almost upon us, and all Atlantis groped through a fog almost too thick to be breathed, this in spite of the fact that the Masters had instructed me that I, as a leader of the majority of the people, must find a way to dissolve the fog, and restore the proper workings of Nature's Law.

"If you fail," the Masters told me. "If you fail, Anghor, the Creeping Mist will become water. The water will coalesce with the salt waters of the Atlantean Sea, and the sea will possess all of the land save certain mountain-tops. Already the weight of the Creeping Mist upon the land is such that the foundations of Atlantis groan."

Now, as I found myself behind that third-entered door in the Building of the Skull, alone in The Laboratory of the City of the Sun, I had a great decision to make. I had been commanded never to use the Creative Fiat without permission of the Masters. The Masters were mortal. What if they were drowned in the sea, when Atlantis sank beneath the waves? They would be, I knew, if I so willed. Could they, then, prevent my use of the Creative Fiat, which after all was merely the Whole of the principle of the Televisor of Speech-Thought? If I refused to use it, it was merely because I was obedient.

I had a great battle to fight within myself, for I knew now the secret of the Creeping Mist. Within The Laboratory of the City of The Sun, I had invented a light-screen-dome, wherein I had concentrated sufficient light from the sun to dissipate the Creeping Mist. I had re-found a lost secret—how to capture and hold the light of the sun. My screen-dome, constructed of the secret metal, revolved eccentrically on a quartz pedestal, so that its rays went forth through all the land, reaching out to conquer the mist as radar of ancient days reached out to conquer the unseen, and sonar of an even elder time reached out to solve the mysteries of sound.

I had experimented with the Screen just once, and in a heartbeat of time after it began its eccentric motion, the Creeping Mist was pushed back from the Laboratory until I could see the buildings of Sian for many parasangs in all directions. I gasped, almost failing to shut off the mechanism before people of Sian should have realized that I, Anghor, had solved the problem of Atlantis' salvation. This would not do. I was human, mortal, and they could compel me to use what I had perfected. But what if they never knew, until it was too late?

My problem then, the decision I must make, was very plain. I could save Atlantis and its mighty civilization for ages yet to come, and The Masters would continue to rule it. Or I could keep my secret until destruction came, make preparations that I myself be sure to survive and rule the remnants saved of Atlantis on the "certain mountain-tops" that would remain above the Atlantean Sea. There might not be many of these, but that mattered not at all. For all of me they could all perish.

For when I was the One Master, and all the Masters were perished, who could prevent my use of the Creative Fiat? No One, ever!

I could live as long as I wished, and people my En-Don—which men had once called Eden—with living things of my own designing and my own desires. They would be beautiful beyond all dreams. The men would be perfection, the women more perfect than perfection, but there would be one variation of the Law; they would all be subject to me, and pay me tribute as I cared to exact.

For days after I knew the secret of how to dissipate, not once, but repeatedly, and so forever, the Creeping Mist, I struggled with my decision. If I kept my secret to myself, millions of human beings would die in the submersion. But had they not earned such end? Had not the Supreme Master so accused them all, and each of them? Who was I to stand in the way of proper Consequences of the Law? Just because I myself had inspired some of the people to rebellion in their minds? Were they any the less to blame for their failures because I had, ever so little, inspired them? Oh, it was easy enough to justify myself.

For days on end I would assure myself that at the proper time I would give the secret to the Masters, that Atlantis might be saved. But always I somehow held it back. There were many days when I was sure I'd keep the secret as my own until after the Catastrophe, and thus emerge into the new world with the secret of Creations, wherewith to design and people the Eden of Anghor.

CHAPTER V

Traitor to His Trust

Even as I wavered between right and wrong, the law and lawlessness, so that I was sometimes not quite sure just which was which, I was fashioning a vessel in which my own carcass would be saved. The vessel was a tube, just large enough for me, a special tube of propulsion, using the power which Atlantis had used for ages upon ages, with a subtle difference. I made a visit to the twin peaks of Ba and Ku, in the warm south, and in each peak I set, and carefully hid, the master magnets to which the magnet in the nose of my vessel would travel unerringly when I freed the power between them with the flipping of a switch.

Thus, even when the great waters broke, and overwhelmed Atlantis, I could step into my vessel, seal it tightly, and let the waters take and turn and spin me wherever they might—but when I pressed the switch, releasing the magnetic power—it was really absurdly simple—the vessel would rise up through the worst maelstrom and rest on the sea between the peaks of Ba and Ku. I would not need then to make haste to leave my vessel. I would be Master of the New World, with no need to hurry. I would be THE Master!

Into this vast indecision I stepped, through the tiny door in the Building of The Skull—forgetting the door, the key, and the building, to become Anghor of twelve thousand years ago.

I sat there, still undecided, with the Catastrophe almost upon Atlantis, when the Three Superior Masters—these titles related solely to natural science, from which all other arts and sciences derived—came to see me. That their coming expressed the general fear I knew. They would ordinarily have bidden me to them. I was a junior, for all my age and knowledge. Beside them, in age, I was a child. A precocious child, but yet a child.

I rose and bowed to them, my heart hammering, for now the decision must be made. If I gave them the secret of the Screen, Atlantis would be saved, and the Masters would remain the Masters, I the precocious child. If I refused it, held it back, Atlantis would disappear beneath the waves and I would be the Master of the New World. Millions would die, but what was death save a scientific fact?

"Greetings, Masters!" I said.

"Greeting, Anghor!" said Rols, the eldest. "We need not tell you why we have come? Nor to remind you that destruction visits us any moment now, any day, any hour?"

"I understand. Destruction hangs over us all, Masters!"

"You have not yet mastered the Creeping Mist? Have not yet even found a clue to its mastery which might provide us with hope? You, though so young, who have given us so many inventions in advance even of our time?"

Here, now, I must decide—and for all time. Whatever I decided, there would be no turning back. If the Masters found I had lied, my fate would be as horrible to me personally as would the fate of all Atlanteans if the Creeping Mist were not abated.

So, what did I decide? In utter horror I heard myself say:

"My Masters, it is hideous failure I must report. I have not solved the secret of the Creeping Mist. I am completely baffled. I have wasted years on nothing of value!"

There, it was out, my decision irrevocably made.

They were very calm about it. They bowed as one, polite as always, exchanged glances, not once asking about or even noting the Screen, its outlines indicated by a tarp of linen, within reach of their hands.

"We must warn Atlantis, at once, but try to prevent fatal stampeding. The end will come with any heartbeat."

They turned and left me. I listened to their footfalls, beating out the knell of Atlantis. I changed my mind, changed it though it meant banishment at least, or worse, for me. I rose and hurried after them, calling out a name. They did not turn, did not seem to hear me. In my mind I intended to call: "Master Bols! Master Bols!"

But not until I came to myself, whoever myself was beside Adam Everyman, in The Lab in the woods behind Westchester, did I realize that I was yelling, over and over again: "Doctor A! Doctor A! Doctor A!"

Amazed, I looked at him. He was indeed Bols the Atlantean Master, which identified him far more clearly than did "Doctor A."

"Yes, Anghor," said Doctor A. "You have followed after me for twelve thousand years to correct the hideous wrong you wrought in Atlantis. Is it not so?"

I shuddered, realized that my body was bathed in horror sweat.

"Send me back!" I said. "I must know fully the depths of my ancient infamy. Send me back!"

But the savant only shook his head at me, as if I were a wilful child.

"Man would not be able to endure himself if he could remember all his infamies," said Doctor A, "which is why it is given only to the supernaturally strong in spirit to remember. But since this is only experiment, out of which we hope to benefit the world and thus balance your personal books, Anghor, as well as our own, you will return, into the heart of the Catastrophe, to remember, record, and bring back.

"After all, you have returned this time without bringing the details of your Mist Dispersing Screen, or the vessel by which you planned to save yourself. Both contain practical data of use to the world. Let us first evaluate what we have, combining your work as Father Wulstan with that of Anghor, and see what we have upon which to base the Total You!"

"How can we total me, or anyone, without opening all the doors of each one's mind—subconscious—House of the Skull—from the Present to the Beginning?"

"With a drop of water from the sea," said Doctor A, "we can postulate the sea itself!"

There was a period of relaxation—breakfast-luncheon-dinner in the Lab, before I should return for answers nobody in The Lab seemed to be able to give me to my satisfaction. I ate without noting what I ate, like a man famished, still sitting in my personal "electric chair." Detective Jan Rober had arrived and made himself at home in the Lab. I grinned at him.

"Checking on your investment, I see?" I said.

"I've been getting a lot of lowdown on you, Adam," he retorted. "For a man who can't remember yesterday, you've been doing an awful lot of remembering. Also, it appears to be exact and very useful remembering. I wish somebody would explain to me just what it's all about?"

"First," I said, "would you like me at last to clear up the mystery of the murder of Marian Slade by Dean Hale?"

If he hadn't laughed aloud I might have thought I had made a mistake, but men didn't laugh at murder, so I took the plunge.

"Marian Slade, of course, was not murdered. You coppers and dicks were doing your level best to make me remember myself. You took extreme measures. You accused me of being a murderer, which ought to shock any amnesiac out of his amnesia. You gave me a name, Dean Hale. I'll bet your contribution was Marian Slade, by an association of ideas! Somebody had to be murdered, you remembered the Lab and how useful a man who might never remember would be to its mentors—and so, Dean Hale murdered Marian Slade. Am I right?"

"Close enough, Adam," he said, a bit ruefully. "But just between pals, I wish you could remember who you are."

"I appear to be remembering a lot of people I have been," I answered. "That is, if you believe in reincarnation."

"This past lives of individuals stuff is the bunk!" he insisted, while the scientists, who ate with us, smiled patronizingly and shook their heads.

"We'll prove it isn't bunk," said Doctor A. "After all, it's nice, or would be, to know you never really go into the grave, or the sea, or the crematorium, wouldn't it? Only your body does."

I didn't believe him, Jan Rober didn't. I doubted if anybody with a grain of sense would. I didn't know how to explain Father Wulstan, or Anghor, but they'd have to be more reasonable than reincarnation to convince me.

"Just what," I asked, becoming more serious, "have you managed to get out of my experiences, if you must call them that, as Anghor? Before you answer, it strikes me that all Anghor's palaver about the creative power of thought is on a par with what we've seemed to prove about reincarnation, a kind of waking-sleeping nightmare! How could anybody except the gods create by the power of thought?"

"You believe in telepathy?" asked Doctor L.

"Between certain minds, perhaps yes; perhaps between the minds of separated twins, or the minds of people so closely associated they can guess accurately what each other thinks. But for one deliberately to transmit thought—well, I've always believed that whoever claimed to do it was a charlatan, a blasted liar!"

"How," said Jan Rober softly, "do you know what you have always believed when you can't remember so much as one yesterday?"

"I don't know," I said desperately. "That thought came out of my very being, so I know it must be true, whoever I may have been yesterday. But remembering something out of the years since one was born, and something out of a pre-existence, are horses of different shades of falsehood. Anghor hints of the Creative Fiat, allegedly an attribute of the Creator only, and of unplumbed depths of power in human thought. I don't believe I am contributing anything."

Doctor A raised his head, and his eyes flashed.

"You did design, while you were away your Televisor of Speech-Thought," he said sternly. "And it is so revolutionary that we're not going to trust it out of the Lab. With the world equipped with it, nobody could ever get away with a lie. I'm not sure the world is ready for such a dose of truth.

"But you belittle the power of human thought. Let me ask you some questions. Which was greater, the unplumbed thoughts of Thomas Alva Edison, or the selected thoughts which resulted in his countless inventions? And which is greater, more important, the invention, or the thought which produced it? And can you insist, after giving it some thought, that anything man uses is not a manifestation of thought, his own or another's?

"Thoughts direct the engineers who plan the Grand Coulee Dam, so that it is set down on paper to proper scale. That design is thought made manifest. Other engineers, working with the design, issue orders, which they have carefully thought out, to many junior foremen, who pass them on. Laborers, carpenters, cementers, plasterers, stone-and-sand workers, receive the thought-out orders, turn them over in their minds, absorb them, transmit their own personal, individual orders to their own hands and feet. The hands and feet, directed by thought, perform the myriad details of labor which result, in time, in the Grand Coulee Dam, greatest work of man existing on earth today save one—the Great Wall of China, also the result of thought."

I reeled mentally, trying to absorb this. It sounded reasonable, too reasonable. It sounded so reasonable I mistrusted it more after hearing it.

"The telephone," went on Doctor A, "is the result of much thought. It transmits thoughts, ideas. How clumsily it transmits them man will know when he can do it without using telephone, wireless or radio, all of which are merely forerunners of communication by direct thought between brain and brain. No, Anghor, we Atlanteans had something, twelve thousand years ago, which man has now lost. If, through the cyclotron, we are able to regain it, or some mechanical channel of it, it may again enrich the world—if, in our opinion, the world is again ready for it, will not misuse it. Misuse of it could destroy nations, devastate the planet."

"Then why fool with it?" I asked. "I'm for letting well enough alone!"

"The world had it before, therefore it must have been intended to have it. If it has it again it is because the time is ripe. Whatever happens to man he has earned it, whether it exalt or destroy him. It isn't up to you to decide."

I tried to think of something else to say, some further objection to offer. The truth was that I was now eager to be Anghor again, to find out just what had actually happened to Atlantis. Of course, I suspected we were somehow being hoaxed, or hoaxing ourselves, but it was exciting—exciting enough to make me forget that I couldn't remember anything of myself.

"Why all the mystery of The Lab?" I asked. "Why may the world not know about all of it?"

"Suppose the world, its newspapers and motion pictures, knew exactly what we are doing with you as the central character in what they would call something like drama of human destiny? Would you mind being annoyed by every crank who'd be sure to intrude?"

I thought what it would be like for me to be away, while hordes of people misconducted themselves in the Lab and gawked at me, and maybe punched and pushed my body out of ignorant curiosity, and shook my head.

"But why do you hide your identities behind letters of the alphabet?" I persisted.

"Maybe, like you, we feel it best not to give our right names," said Doctor G, the first words I had ever heard him speak. "No, Adam, since we are delving into the unknown, perhaps the unknowable, since we are using human beings against the beliefs of other human beings, we maintain anonymity. Here each of us is Doctor Jekyll of the Lab. At our homes, outside, away, when we take time to visit them, we are humble Hydes who wouldn't think of doing anything unorthodox, or even of using animals in our tests! I'm sure you can understand our wish to protect ourselves against intrusion."

"But how about my metal bird, and the other designs you have made available to—whoever you have made them available to?"

"Oh, that's very simple," said Doctor A, grinning. "We have given everything to the world in your name, Adam, in your right name! We've done it through Jan Rober, a very wise and useful man, who acts as your agent."

I jumped to my feet.

"Then you know who and what I am, all of you? What is my name? Where do I practice law?"

"You still don't remember, Adam?" asked Doctor A, softly.

"No, I don't remember!" I almost shouted it.

"Good! Then what your real self, represented by Jan Rober, does in the name of humanity, can't possibly influence the excursions of Adam Everyman! I think, and my colleagues agree with me, that it is better you remain, for the time of our experiments, and your excursions, Adam Everyman! Of course if by chance you remember, we shall do nothing to interfere. After all, you came here to be induced to remember—remember?"

I gave the matter some thought. I could see where conflict could interfere with what we were doing, and that my own personal rediscovery would bring about that conflict. Maybe I had a wife, family, who would object to all this if they knew. I almost asked Jan Rober whether I did have a wife and children, but thought better of it. It wouldn't maintain my peace of mind to know I had. Better leave it as it was.

"I'll play along," I told them. "Where do I go next?"

"Into your magnetic vessel, Anghor," said Doctor A, "at the exact moment doom cracks down on Atlantis!"

CHAPTER VI

Master Island

Yes, the Catastrophe came and I was ready. Some few Atlanteans had fled to the great continent to the south. Some had fled to the mountain tops. The Masters had chosen to go down with their land, as masters of vessels went down with their ships in the days when vessels traveled on the face of the sea.

For myself, I had my vessel, completely equipped for myself. In it was every comfort. I could lie at full length and control every movement of the vessel. I could cause it to stand on end, so that I stood erect, or I could lie on my sides or my stomach or my back. Always before my face were two windows. One was an ordinary window, through which I could see my immediate surroundings. The other window was my own development, kept as secret as the Mist Screen, of radar.

In this radar I could see any part of Atlantis at any time. And so, within my vessel I saw the terror strike. I studied, each in turn, the great cities of my native land. Their minarets, their spires which, before the Creeping Mist came down, were like new snow reflected in the sun. Never in the world were there beauties made by man such as were found in the cities of Atlantis. There were four great cities in the richest valleys, beside the most beautiful lakes, and countless smaller ones, and not even the proudest local dweller could have said which city of Atlantis was the most beautiful.

Surely Sian, for example, must have been even grander than the New Jerusalem which our ancient prophets foresaw. Perhaps heaven itself was what man saw when he looked upon the cities, the fields, the blue canals, the gorgeous spires, all the glory of Atlantis.

But for me it might have survived for further ages. Who can say? I might make a journey sideways in time, as we sometimes do among the Initiates of Atlantis, and see what would have happened if I had decided to give up the secret of the Creeping Mist. But now it was too late, though I may elect to do the sideways journey from the Master Island which is now, for a few short hours, a mountain peak.

The Creeping Mist became all at once a roaring maelstrom. Its mists became waters as the waters in higher heavens came down to join the mist. Over the hills, through the great divides, up the valleys of the rivers, came the blue-white waters of the Atlantean Sea. Atlantis, the continent itself, began to shake and tremble as if held up by palsied undersea legs that could no longer hold its weight. The land tipped, and the sea rushed over it, tilting it the more.

So I watched the sea strike Ogra, the City of the Morning-and-Evening Star. What a monster was the sea, its forerunning wave higher than the tallest spire in Ogra. It rushed with all its vast weight upon the city. People were like ants scurrying to safety. I watched them, refusing to think that but for me they could have had a chance to live.

The water struck. The spires disappeared. Mighty buildings were pushed over, to crash to the trembling earth, as if by irresistible monsters, and the water possessed the ground before the masses struck. But one knew they struck for mighty geysers were hurled aloft from underseas, where weight and power and energy were in conflict. But ever the sea moved on. I saw the great wave approach Sian, and held my breath. Had I miscalculated? Would my tiny vessel withstand the might which had ground Ogra into nothingness? I was sure it would, for I had calculated how high the water would rise, how great would be its mass, how much pressure on the ribs of my vessel would be required to hold it away from myself.

The sea poured over me, and over Sian. Through my radar screen I watched people, men, women and children, gathered up in the heart of the seas, tiny things in the midst of mighty maelstroms, and hurled hither and yon, up and down. I saw bodies by the hundreds, thousands, ground to bits among the undersea wreckage of the most beautiful buildings in Sian. I saw animals spun in all directions. I saw precious things, tapestries, robes, screens, furnishings beyond price, taken into the heart of the rushing tide, and borne away into limbo as if they had been nothing. I saw Atlantis the proud, the mighty continent of old, pushed beneath the waves, to rise no more. I saw the sun go out on it until it should rise again—if ever—and knew to the fullest realization that the fault was mine.

Canals were gone, lakes were gone, valleys were buried in the darkness of the deep sea. Hungrily the waves crawled up the sides of the highest peaks, and some of them for a time were under water, long enough to drown the desperate who had managed to flee so high, and then rose again as the continent settled in its new resting place.

I had been positive that the twin peaks of Ba and Ku would remain. And so they did. I watched the cities fall away beneath me as I soared above them in my vessel. I saw countless bodies follow the cities, sucked under until the resurrection day by the plunging, ruined, battered cities. I saw the darkness claim them. I saw great creatures of the deep come over the land riding deep and riding shallow in the conquering sea, and I saw the vastest creatures of them all, feed upon the people my carefully kept secret had slain.

I was not happy in the horror, until I remembered that now, in effect, I was The Master, and so a kind of god. I had seen enough. Now I must hurry to my Endon, my Eden, there to be a god in fact and by using the Fiat to create a world of my own, in my own image if I wished, or in any form I might desire.

Riding through the waters, now deep under, now just below the surface, now on the surface which was becoming swiftly still, I threw the switch which connected my vessel with the magnets on the peaks of Ba and Ku. Instantly, like a homing pigeon, the vessel responded. Its speed was swift, until the water along the sides blurred my vision, so that I cut it down. To think to decelerate was to decelerate. To think speed was to gain speed—for thought was the motive power which guided the magnet by which my vessel traveled, the switch its signal to perform.

So I came to the surface of the blue sea which lay between the sunlit peaks I had chosen for myself. They still were damp as from a lengthy rain. The water had covered them, long enough to drown all living things upon them save the trees, the plants. The twin peaks were mine. Not one person lived among all the many bodies that floated in the sea about me, and doubtless in the seas beyond the peaks. And with all industry the sharks and great whales, the behemoths and leviathans, were disposing of the dead.

I took my time until the scavengers had cleared the waters and there was no chance of infection. Disease had long been banished from Atlantis, but there had never been such an epidemic of death in the land before, and so it would have returned but for the scavengers.

When all was done I quitted my vessel, stood ashore, raised my arms above my head, rejoiced that my plan had succeeded. This was Eden indeed, with all green fruits and trees and vegetables man might desire, for Atlantis cultivated every inch of all its land, including these. Here was my Eden.

I ate and drank from my stores. I was sure I could produce food at will, or water at my desire, merely by desiring. I had not used Creative Fiat yet, but I knew how. There was no hurry, there was plenty of time. A god had no need to make undue speed.

When I was ready, and not before. I sat down under a fig-tree and thought:

"What shall I create in this Eden?" I began to form pictures in my mind, to make mental designs of the living things I would create. I would begin small. I would, first, make a simple tree. I saw a stately palm in my mind, like no palm that ever grew on Atlantis anywhere. I saw it in every detail, its fronds, its fruit, its life juices, its roots, its velvety bark.

I saw it. I spoke the word: "Be!"

And it was! The Fiat operated for me! I needed no further proof. Now, as for animals there were enough in the sea. They might come out in time to populate the earth. Just now I had no need of animals.

"There shall be men, but not the tall white blue eyed man of Atlantis," I decided. "I shall make several men, of different colors, of different attributes, of different heights, different appetites, different mentalities. First, I shall bring a brown man—and why not his mate at the same time—into being!"

I saw the man and his mate in perfect detail, whole.

I spoke the word, and nothing happened, nothing whatever! More sharply I spoke it again, but it did not operate. I gazed at the tree I had made, to make sure—and as I thought of how I had completed the tree, the thought created its other self beside it, so that there were two new palms on the first of my two peaks. But man I did not bring into being.

I tried red men, and failed. I tried black men, failed again. I tried yellow man—failure, all failures!

Would my dream not come true then? Was I destined to live out my time entirely alone on this Eden I had selected? I would not have it so.

I could manufacture stuff from electronic force. I had with me in my vessel every ingredient, every element, every instrument. I had stocked my vessel against every contingency, like a good seaman, by which I might build the skin, flesh, bones, cartilage, nails, all the intricate diverse parts of man.

So all in a day I built the forms of a red man, black man, yellow man, brown man—and for each I built a mate at the same time.

Then I commanded them to obey me, to rise, and breathe, and walk, and go, and live as men and women. In their brains which I had created I wrote for each color a language which should be all his own.

Now they obeyed me!

They rose, and stood, and turned their eyes upon me, eyes that should have been alive, but were instead the eyes of the dead—the eyes of things which had never lived, nor ever would—moving things that did not live!

I've no way of knowing what their metallic minds thought of me, but as if they were, all eight of them, possessed at once by the same evil genii, they launched themselves at me, shrieking at me in their several tongues.

I had not expected this. I slew a man. A woman I slew by accident. The others pulled me down, clawing at me, biting, scratching....

I knew, as I knew that they were killing me, that these people would survive, for I had made them strong, and that in them—soulless, merciless, heartless though they were—I would survive to the end of time. Perhaps, eventually, the Masters, or other Masters would do that missing thing, speak that fruitful word, which would bring the light of life into those dead eyes, but I had little time to think upon it.

For they were tearing me apart, and I was begging for mercy from the merciless. I cried out, but they did not understand, how could they, when what I called aloud was:

"Doctor A! Doctor A! Doctor A?"

I stepped from beneath the hood in the Lab in Westchester. The table before me was littered with new sketches I had done. Doctor A and his colleagues were jubilant.

"Here's a perfect job of city planning!" he cried. "Here's the answer to the housing problem! This concentration of great force is the answer to the atom bomb, for it was developed for defense as well as offense. It was known, you told us, ages beyond ages ago to Atlanteans, but not used for all those ages because the world was at peace. But it could be used to cause continents to sink as Atlantis sank."

I stared at the scientists.

"Don't give it to mankind!" I cried. "I have seen such destruction. I caused it. Don't make me the instrument to bring it about again. Keep it secret, for all our lives, and afterward, unless somewhere in the Secret Wisdom of the Sages of the Past, there is an answer to dreadful knowledge such as this, to make it safe for men to manage!"

They understood me, every one of them, for they were men of intelligence beyond their time—and why not? Three of them were obviously the Three Masters of Atlantis!

"To trace every possible knowledge of man," said Doctor A, "we must trace in detail the past of every man on earth. That we cannot do. To trace all the past of even one would take generations."

"But we can begin," I said eagerly. "I shall devote my life to it. And if you're somehow giving the world the benefit of what we're doing and believe that man can learn from the evil in his past, dredge up my disastrous lives if you wish, also."