The Project Gutenberg EBook of ΝΕΚΡΟΚΗΔΕΙΑ, by Thomas Greenhill

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

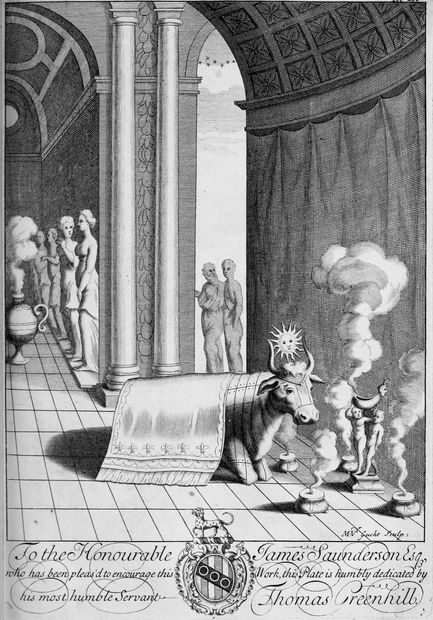

Title: ΝΕΚΡΟΚΗΔΕΙΑ; Or, the Art of Embalming;

Wherein Is Shewn the Right of Burial, and Funeral

Ceremonies, Especially That of Preserving Bodies After the

Egyptian Method. Together With an Account of the Egyptian

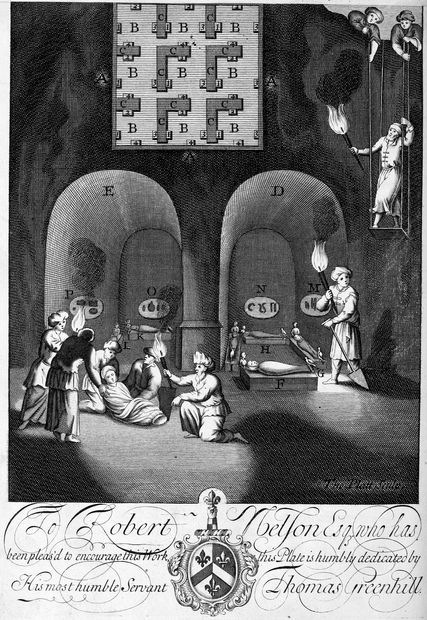

Mummies, Pyramids, Subterranean Vaults and Lamps, and Their

Opinion of the Metempsychosis, the Cause of Their Embalming.

As Also a Geographical Description of Egypt, the Rise and

Course of the Nile, the Temper, Constitution and Physic

of the Inhabitants, Their Inventions, Arts, Sciences,

Stupendous Works and Sepulchres, and Other Curious

Observations Any Ways Relating to the Physiology and

Knowledge of This Art.

Author: Thomas Greenhill

Release Date: September 1, 2018 [EBook #57829]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ΝΕΚΡΟΚΗΔΕΙΑ ***

Produced by Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery; Baron Herbert of Caerdiff; Lord Rosse, Par, Marmion, St. Quintin and Shurland; Lord Lieutenant of the County of Wilts and South-Wales; Knight of the most Noble Order of the Garter, and President of Her Majesties most Honourable Privy Council.

I count it no small Happiness, in an Age so Censorious as this, to have found a Patron so universally admir’d, that I am under no apprehension of being thought a Flatterer, should I make use of and indulge all the Liberty of a profest Panegyrist; but that is what a sense of my own Inability and Your Lordship’s Modesty forbids: It is sufficient for me, that, under Your Lordship’s known Learning in Antiquity and History, both Antient and Modern, my weak Endeavours at restoring a lost Science may be secure from the Assaults of the Envious or the Ignorant.

I have nothing to fear from the Animosities of Parties, since how inveterate soever they may be against each other, yet they all agree in this one Point, to Esteem and Honour Your Lordship, who are the Atticus of the Times, by Your Virtues endear’d to all sides, and each believing that not to Value Your Lordship, would be to discover such an aversion to Honour and Virtue as the worst of Men would abhor.

Your Virtues, my Lord, are so conspicuous, that they give you that Natural and Rational Right to true Nobility, which the Roman Satyrist so justly exprest:

I will not dispute whether or no there be any Intrinsic Value in a long Descent, or whether that be deriv’d from the necessity of a Subordination essential to Government, or else from the just Reward of Virtue, which ennobles all the Posterity of the Possessors of it, it being here a very useless Disquisition since Your Lordship’s Family is of so very high an Original that none can boast a greater Antiquity, and that Your Lordship is possest of all that Merit which first distinguish’d Man from Man, and gave a Preeminence to the Deserving. Among all the Excellencies which thus dignifie Your Lordship’s Character, perhaps there is none more eminent than Your Protection and Encouragement of Arts and Sciences, to which the English World owe the incomparable Mr. Lock’s Essays on Human Understanding, and other Works extreamly beneficial to the Public. Neither do I in the least question but Your Lordship’s Protection of so excellent and useful an Art as Surgery, will render it as flourishing here in England as it is in any other part of the World. ’Tis true we are not wanting of some extraordinary Professors of that Art, but I could also heartily wish we had not a greater number of Bad, and yet perhaps the chief occasion of this may be the want of a due Method of Encouragement, by which the modest Endeavours of young Proficients are eclips’d, and which (to make a Comparison) like tender Plants, are nipp’d in the Bud and perish for want of Watering.

Now as the want of Opportunity has been in some respect a prejudice to my Business, so also the want of Encouragement has in a great measure been a hindrance to this Work: For what regret of Mind must it needs occasion, to find none esteem’d but such as speak Experience in their Looks, and that Youth should be despis’d tho’ never so hopeful and industrious, meerly because of a particular number of Years, and what an interruption must it be to our painful Studies, to think that even the best Performances of this kind are contemn’d because they are chiefly a Collection, when on the contrary it is receiv’d as an establish’d Maxim, that such as Travel into Foreign Countries, are not only the most capable to describe them, but also whatsoever they relate is look’d upon as the sole matter of Fact and Truth, when many times Business is better transacted by Correspondence, and those that have been at the trouble, expence and danger of Travelling have come home no more improv’d than they went out, except in the Fashions and Levities of the Age, yet are we commonly so imprudent as to value Things meerly for their coming from a far and at a great deal of Expence; but whilst we admire those Novelties, we are often misled and deceiv’d by meer Fables and imaginary Stories of such Things as neither are, nor ever have been.

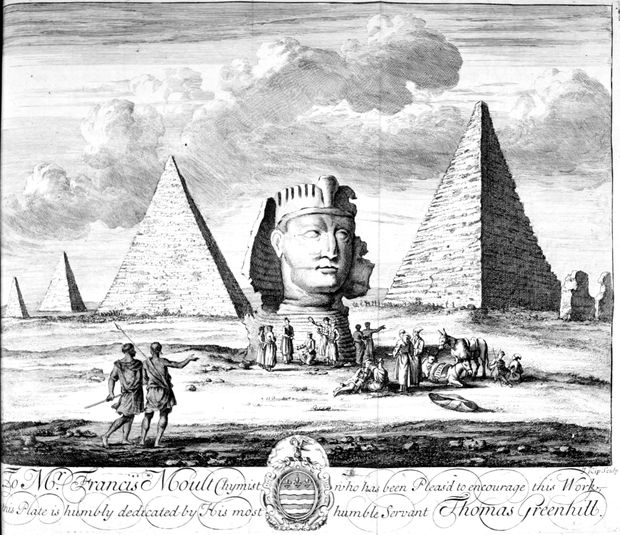

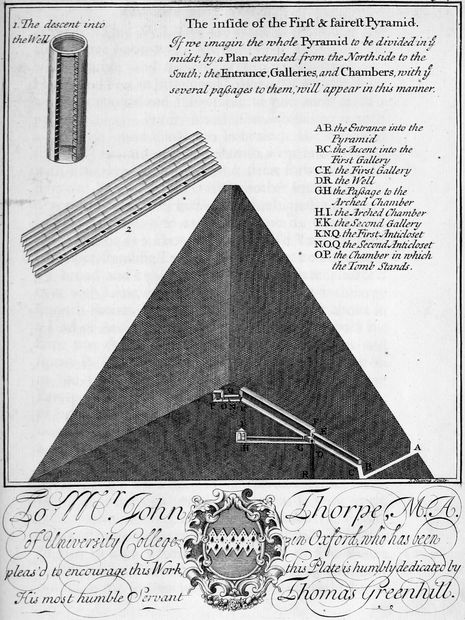

This I speak not in prejudice to Travelling it self, which, if rightly understood, is certainly the greatest Improvement in the World, and I could heartily wish I had had the opportunity of its Advantage, but on the contrary I do it chiefly to show that it is not impossible to give a tolerable, if not the best Account of the Ancients without it; for what can any one, who now travels into Egypt, learn or see but such a ruin’d Country, that the very Place is hardly known where those wonderful Cities Thebes and Memphis stood, except what is Traditional or extracted from the Writings of the Ancients. ’Tis true, the learn’d and accurate Mr. Greaves has given us the best Description of the Pyramids, but then this was both because they are at this Day in being, and to be view’d by Travellers, as also that he carry’d along with him the best contriv’d Instruments for taking their exact Altitudes and Dimensions, which few besides that see them trouble themselves with, but are content to say, they have seen them; nevertheless Greaves can neither give us the Names of the right Founders of them, nor any certainty whether there were perpetual burning Lamps in them, or a Colossus or Statue on the top of the bigger Pyramid, or, in a word, by whom and to what end the monstrous Figure of the Sphinx was built.

But however the aforesaid Reflections are not the only Discouragements to Industry and Study; to see our Profession over-run by Quacks and Mountebanks, and that Valet de Chambres are suffer’d to Bleed, dress Wounds, cut Fontanells, and perform the like Operations, is what has reduc’d Surgery to so low an ebb. In like manner the noble Art of Embalming has been intirely ruin’d by the Undertakers, as also the Court of Honour much prejudic’d, of which Your Lordship has been twice Supreme Judge; from whence it is the Balsamic Art is now-a-days look’d upon as a very insignificant Thing, and not a little despis’d, whereas the Knowledge and Practise of that Art is both useful in Natural Phylosophy, Physiology, Physic, Surgery and Anatomy, as I hope I have fully prov’d in the body of my Book, over and above that the History thereof leads us into the first and best Antiquities of the World. Your Lordship therefore being both a great Admirer and Encourager of Things of this nature, I hope, thro’ Your generous Protection, not only to secure my self against the contempt of all Critics, but also to be enabl’d to continue and complete my intended Work, and this has also been one Reason why I have thus vindicated Surgery, the Art of Embalming and my own Collection; in which, altho’ I am not thoroughly satisfy’d that there is any thing worthy Your Lordship’s perusal, yet this I am sure of, that Your Candour will appear the greater, by condescending to accept my mean Performance.

And here, my Lord, I have the temptation to loose my self in the Field of Your Praises, but that I know both my Patron and my self too well to indulge the agreeable Contemplation. Were Your Lordship like common Patrons, I should do like common Dedicators, speak of the admirable Temperance of Your Life, Your Moderation, the Wonders of Your Conduct when You were Lord High Admiral, which Office was Administer’d by Your Lordship to the Universal Content and Satisfaction, both of the Merchant, the Officers and Sailers; Your Lordship’s Prudence, Judgment and Sincerity in Your high Post of President of Her Majesties most Honourable Privy Council: And I might extend my Considerations even to the great Happiness such a Person must possess, who is so generally valu’d and esteem’d both by his Queen and Country; but what is so well known I shall leave as wanting not the help of any Panegyric to make it more evident, and content my self with the Honour and Satisfaction of being permitted to Subscribe my self, My Lord,

It is not only the Authority of King Solomon, the greatest, richest and wisest of Men, that convinces us There is nothing new under the Sun, but also common Observation daily shews us the Truth hereof; for whether we respect Kingdoms and Monarchies, Cities or Villages, with their Civil, Military and Rural Transactions; whether we consider the Ambition of Kings and Princes, or the Captivity and Subjection of the Common People; or if we look into the various Sects, Religions, Habits, Customs, Manners, Arts and Sciences that are in the World, we shall in all things find we are but Imitators of our Fore-Fathers, and tread only in their Footsteps.

iiThe same Thing is acted to Day which was done a Thousand Years ago, and this, after a Vicissitude of fantastic Alterations, will in another Century come into Fashion again; so that we move like the Cœlestial Orbs, in the same Circumvolutions, and our whole Life is but

It is the same with Books and Writings; for tho’ public Advertisements do daily inform us, that some Work or other is continually on the Stocks, yet is it but the same Story inculcated over again, in another Language, different Volume, larger Print, additional Sculptures, and some new Alterations; or else it is but a Translation, with Annotations, Comments, and a Table annex’d, which serve for new Amusements and the Maintenance of the Booksellers. Others which bear a greater Repute in the World, as being penn’d by the more Learned and Ingenious Persons, in a very Concise and Elegant Stile, are generally nothing but some new fine-spun Virtuosi Suggestions, extracted from an almost forgotten and out-of-fashion Hypothesis, and each Improvement in Modern Arts, has undoubtedly ow’d its Original to somewhat hinted to us by the Ancients.

iiiAll this I freely acknowledge to be my own Case, with this difference only, that I know my self deficient in that solid Learning and admirable Stile they were wont to use; yet for your encouragement to peruse this Treatise, I can assure you, you shall hardly find any other Book which so generally, particularly and completely handles this Subject: Besides, I can justly aver that I devis’d and compil’d the greatest part thereof before I met with any Author that gave me so much Satisfaction as I have since had; and notwithstanding my Notions were in a great measure agreeable to theirs, tho’ unknown to me, yet will I modestly submit and attribute the Invention thereof to them, First, As being my Seniors, and who Wrote before me, and, Secondly, as infinitely the more Learn’d and better Qualify’d Writers. Nor does this Submission detract the least from my Labour, it having been to me the same thing as a lost Art: And I would gladly be inform’d, by any one at this Day, of the true Method of the antient Egyptian Embalming; nay, would be content only to know the more Modern, tho’ more excellent Way, that of Bilsius.

We must therefore grant that the Ancients knew many Things, which in process of Time, iveither thro’ Fire, Inundations, hostile Invasions, or other Accidents and Devastations, have intirely perish’d, and still remain so, as Pancirollus fully shews; or if we have any superficial Knowledge of them, as is somewhat apparent from our Modern Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, &c. yet are we even at this present so vastly deficient in the very best of our Imitations, that none have ever hitherto arriv’d to any tolerable Perfection; nevertheless should any one so perfectly apply himself to the Study of one of those lost Arts, as to make a new Discovery therein, I hope you would allow him the same Praise as if he had been the first Inventor; and, for my part, however I should fail in answering your Expectation, of what is seemingly promis’d in the Title-Page; yet, thus far I am pretty sure, that I have given more light into the Matter, than has been done by any of those imperfect Accounts of Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, &c. And tho’ some Things that I say may seem to want Authority, yet for the most part, should I have made all the Quotations I could have brought to prove my Assertions, it would have extended this Volume to a much larger size than I intended; wherefore I have in a great measure designedly omitted them, to the end I vmight avoid Prolixity as much as possible, and in other places I have us’d their Words expresly as my own, not to detract from them, but to be more concise, and have in several places not mention’d their Names, for the aforesaid Reasons: So I do here, once for all, with submission, Apologize for my self, that the censorious World may not repute me an ungrateful Plagiary.

I acknowledge therefore this my Labour, in one respect to be a Collection, in all to be still deficient of that Perfection which so noble an Art deserves; yet in some Things I have improv’d it, and in others apply’d it to those Uses which have scarce before been thought of. But all the Satisfaction I have herein, is to think that I have perform’d my Duty, in exerting my small Talent, with the utmost Care and Diligence, for the Benefit of our Company; and if my Work does not perform what is intended and desir’d, it will nevertheless be Useful, Pleasant, and serve to Divert you, which Horace says is the Perfection and Chief end of all Writing:

1. Undertakers.

Page 24. Line 24. for Jujiæ read Injice, p. 31. l. 9. for Nolanus r. Santorellus, p. 111. l. 31. for on r. in, p. 127. l. 29. for Marenuna r. Maremnia, p. 230. l. 12. for Romans r. Grecians, p. 330. l. 26. for Scardonius r. Scardeonius.

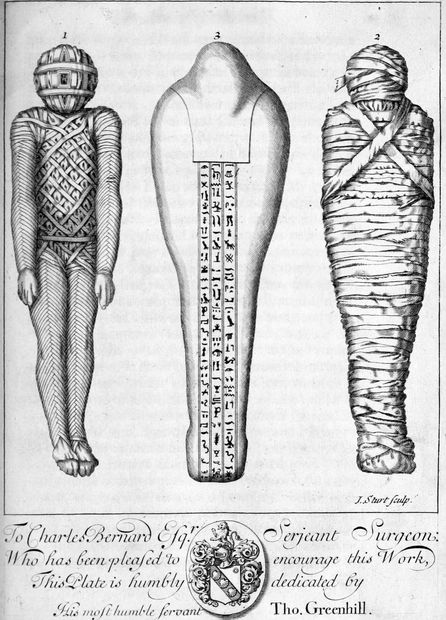

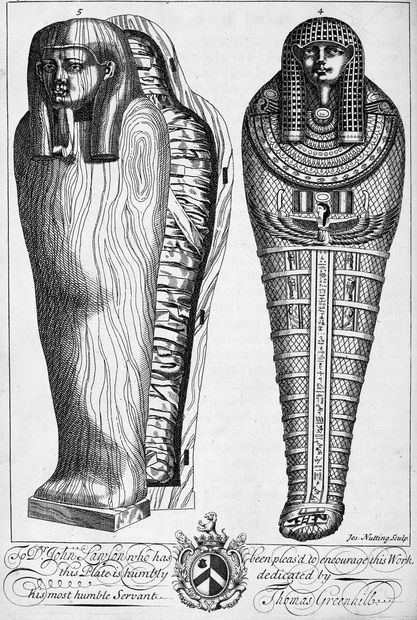

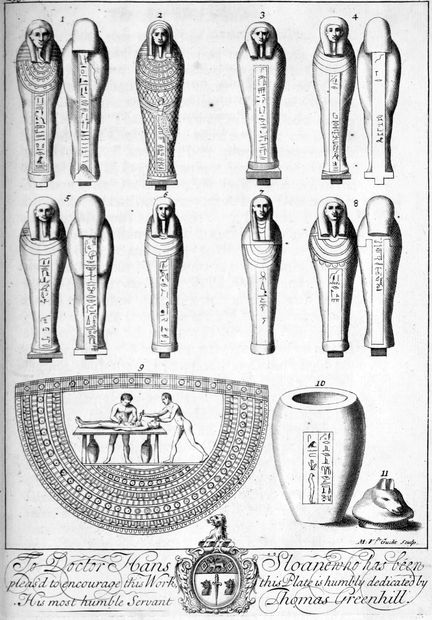

To Charles Bernard, Esq; Sergeant-Surgeon to Her MAJESTY, Present Master of the Surgeons Company, and one of the Surgeons of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital.

If the Excellency of any Art consist only in its Usefulness, or if it derive its Preeminence from the Object, with which it converses, it necessarily must follow, That the Profession of Surgery is the Chief of Arts, since it is employ’d about so noble a Subject as Man; and therefore the Greeks have thought fit to call such manual Operations The Art of Surgery, which otherwise might as well have been apply’d to any Mechanick Trade.

2Thence it is Anatomy and Embalming are also equally to be esteem’d, since they are not only Branches of this Art, but likewise absolutely necessary to be known by its Professors; the one informing us of the constituent Parts of the Body, and the other preserving it for ever in our Memories.

The first has been Learnedly Treated of by our own Countrymen, as well as Foreigners, and is admirably perform’d even at this Day in our Anatomical Theatre; whereas the last, I know not by what Fate, is surreptitiously cut off from Surgery, and chiefly practis’d by ignorant Undertakers.

For the Honour therefore of our Profession, I have undertaken to vindicate The Art of Embalming, and will prove it to be no less antient and noble than Surgery it self. In order to this, I will first shew both the antient and modern Methods of Embalming, as practis’d by the most learned and expert Physicians, Surgeons and Anatomists, and then proceed to detect the Frauds and Subtilties of the Undertakers or Burial-Men, to the end the World being made sensible of their Abuses, may the easier be reconcil’d to a right Opinion of the legal and skilful Artist; but before I proceed to acquaint you with any farther particulars, I shall content my self to shew you the Authority and Reasonableness of the Use of Embalming, together with the many Advantages that accrue thereby. |Useful in Natural Philosophy and Physiology.| First, I presume, it may not be a little Entertaining, should I relate how far the Knowledge of this Art may be necessary in our very Domestic and Culinary Affairs, such as, Tanning, Painting, Dying, Brewing, Baking, &c. as also in Confectionery, by Conserving all sorts of Roots, Herbs and Fruits, and Preserving Wines 3and Juices; for this Art being grounded as well on Natural Philosophy as Physiology, it not only teaches us how to Improve our Drinks, but our Aliments likewise, and not only to give a grateful Taste in Cookery, and thereby to whet the Appetite, but also to Preserve fresh Meats, Fish, Fruits, &c. beyond their wonted duration.

These Things however I will pass by for the present, that I may come more immediately to my principal Intent, which is to shew how a Body may be so Preserv’d, that by the help of Anatomy we may trace its minute Meanders, and investigate the secret Passages thereof, without being hindred by any offensive Odour or contaminating Cruor.

By this Art the Naturalist may be enabled to Collect and Preserve a numberless variety of Birds, Beasts, Fishes, Reptiles, Herbs, Shrubs, Trees, with Things monstrous and preternatural; as likewise those which are more rare and not appropriate to his own Climate, and this for compleating his Musæum or Repository with all the Curiosities and Rarities in the Animal and Vegetable World.

By this Art the Physician learns the situation and use of the Parts of Man’s Body, with the several alterations and changes in the Juices, as well in their healthful as morbid State; and consequently knows how to preserve and confirm them free from all Diseases, as likewise to correct and put a stop to malignant and putrid Fevers, which otherwise must inevitably destroy the sick and weak Patient.

By this Art the Surgeon, in a rightly prepar’d Skeleton, sees the natural Position of the Bones, and proper Motions of each Part, with the true and natural 4Schemes of the Veins, Arteries, Nerves and other curious Preparations; which not only teach him the difference between the Muscles, the similar, dissimilar, and containing as well as contained Parts of the Body; but likewise how, in performing each Operation, he should skilfully avoid Cutting what he should not, and destroying the Function of that he is to relieve. He is also hereby instructed what Remedies may be found out against Gangrenes, Sphacelus and other Distempers that are judg’d Incurable without being extirpated by Knife or Fire: Who then can sufficiently admire and value this Noble Art of Embalming since it tends to the Conservation both of Life and Limb?

For tho’ Anatomy gives us an Insight into these Things in general, yet is it deficient without the Balsamic Art, in as much as it can neither so particularly nor frequently shew us, what in conjunction with it, may without any offence be Contemplated at any Time, and as often as we please.

Thus may we entirely conquer and accomplish that Delphian Oracle, Γνῶθι σεαυτὸν, by making most of our Disquisitions into Human Nature by Dissections: And tho’ Brutes may sometimes be useful in Comparative Anatomy, yet Man being the Epitome and Perfection of the Macrocosm, his Body shews a more wonderful Mechanism than all other Creatures can do, as one thus very elegantly expresses in Latin: Hominem (says he) a DEO post reliqua factum fuisse; ut DEUS in ipso exprimeret, sub brevi quodam Compendio, quicquid diffuse ante fecerat.

The present Age therefore accounts the chief Use of this Art to be in Anatomical Preparations; but I shall shew another more antient and more general, 5which is the Preserving a Human Dead Body entire, and which is properly term’d Embalming: More antient, I say, as having been first devis’d and practis’d by the Wise and Learned Egyptians, and more general in that it relates to every particular Person, yet is it by most despis’d and look’d on meerly as an unnecessary expensive Trouble; so that unless I can convince these People to the contrary, I must not expect to find my ensuing Labours meet with any Favour. But before I affirm The Art of Embalming to be a particular part of that Duty, which obliges all Mankind to take care of their Dead, |The Right of Burial and Funeral Ceremonies.| I shall give some cogent Reasons to prove the Right of Burial, what Things are necessary thereto, whether Ceremonies are needless and superstitious, or Monuments vain-glorious, &c. and this shall be as Nature dictates, the Law of GOD appoints, and the Law of Nations directs and obliges.

First, Sepulture is truly and rightly accounted to be Jus Naturæ, by reason the very condition of Human Nature admonishes us, that the spiritless Body should be restor’d to the Earth, from whence it was deriv’d; so that it only pays that Debt of its own accord, which otherwise Nature would require against its Will. Thus, in the beginning of the World, so soon as Adam had transgressed, |Ordain’d by GOD himself.| GOD said to him, Gen. 3. 19. Thou shalt return to the Ground, from whence thou wert taken; for Dust thou art, and unto Dust thou shalt return. Whence Ecclesiastes, 12. 7. says, The Dust shall return to the Earth as it was: and the Spirit to GOD who gave it. Likewise patient Job thus expresses himself, Job 1. 21. Naked came I out of my Mothers Womb (which David also calls the Lowest part of the Earth, Psalm 139. 15.) and naked shall I return thither. Upon which Quenstedt 6thus Comments, p. 10. De Sepult. vet. He shall not return again into his Mothers Womb, but unto the Earth which is the Mother of all Things. Upon which occasion read also Ecclesiasticus, 40. 1.

Hence it is the Heathens have generally follow’d the same Custom of restoring the Dead to their Mother Earth; since it is but according to the course of Nature, for all Things to return at last to their first Principles, and that so soon as ever a Disunion or Dissolution of the Parts of Man’s Body shall be caused by Death. That each Thing has ever immediately requir’d what it gave, is excellently describ’d by Euripides, in one of his Tragedies call’d the Supplicants, where he introduces Theseus Talking after this manner:

Hereby it plainly appears that we really possess nothing of our own, and what we seem to enjoy, is but only lent us for a season, and must be restor’d again when ever we die, which is agreeable to that Expression of Job, in the latter part of the above-mentioned Verse and Chapter. The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the Name of the Lord. Also Holy David, Psalm 146. 4. (speaking of Man’s Frailty and Mortality) says, His Breath goes forth, he returns to his Earth. Here he emphatically calls it his Earth, both because he was made of it, Gen. 2. 27. and must return to it again, Gen. 3. 19. and by reason he has a Right to a Burial-Place in it.

The same is likewise Taught us by Cicero, where he says, Reddenda Terra Terræ: That the Earth (meaning Man’s Body) must be restor’d to its Earth; which also gave occasion to the antient Philosophers to contemplate the Beginning and End, or the Life and Death of Man, that thereby they might be the better able to Teach us what we really are in Nature, and how little we have to Boast of: The very Thought of which put an old Poet into a Passion and Admiration, expressing himself thus in gingling Monkish Verses:

8Methinks the very Consideration of this should cause us to lay aside all Pride and Vanity, and serve for a perpetual Memorial of Humility and Obedience to our Creator, who as he was pleas’d to endue us with Rational Souls, and to give us Dominion over all Things here below, yet, that we might not be thereby puffed up and tempted to forget him, he wisely formed us of the Dust, and, in his good Time, will reduce us to Dust again. Thence Divine Plato assures us, that the End and Scope of his Philosophy was only The Consideration of Death.

In Obedience therefore to the Laws both of GOD and Nature, Sepulture undoubtedly was at first Instituted, and if either Antiquity or universal Custom can prove a convincing Argument, you may account it as antient as the World it self, and us’d by all Nations tho’ perhaps in different manners; for you must allow, so soon as Death came in by Man’s Transgression, it necessarily follow’d that some care must have been taken to Bury his Carcass. The first Instance of this that we read of, in the Sacred History of the old Testament, is how Abraham, the Father of the Faithful, Buried his Wife Sarah in the Cave of the Field Machpelah, which he had bought of the Sons of Heth for a Burying-Place for his Family, Gen. 23. 19, 20. There also St. Jerome asserts Adam the first Man was Buried; and Nicolaus Lyranus and Alphonsus Tostatus are of Opinion the Four Patriarchs were Buried there likewise with their Wives, Eve, Sarah, Rebecca and Lea, all which you may find explain’d more at large in Quenstedt, p. 2, 3, 4.

Now this seems to have been one of the first Causes of Interment, to wit, that it being the course of Nature, 9for Bodies depriv’d of Spirit or Life to corrupt or stink; and the Medicinal Art being little known and less us’d in those early Days (without the Knowledge of which it was impossible to preserve them) there remained no other way of securing the Living from the pestiferous Exhalations of the Dead, than by burying their Carcasses in the Earth, and so removing such miserable Objects out of their sight; which seems clearly intimated by the aforesaid Example of Abraham, when, being in much trouble for the Loss and Death of Sarah his Delight, he spake thus unto the Sons of Heth, Gen. 23. 4. Give me a Possession of a Burial-Place with you, that I may Bury my Dead out of my Sight. (LXX. θάψω τὸν νεκρόν μου, ἀπ’ ἐμοῦ) where it is to be observ’d, that he no longer calls her his Wife, but his Dead; as knowing that those alterations, which she must in a few Days inevitably undergo, would have deterr’d him from the very Thoughts of her, if he had not earnestly sought for and obtain’d a Burying-Place, where he might hide her out of his Sight.

This is to be look’d upon as the second Cause or End of Burial, to wit, that it being not only disagreeable to the dignity of our Nature, but also occasioning great sadness of Mind, for the Living to see what dismal Accidents and Calamities befall the Dead, that we should free our selves from the Apprehensions and black Idea’s such Objects are naturally apt to inspire, by removing them out of our Sight and Mind, by a timely Sepulture: For as Demosthenes said in a Funeral Oration, Leniatur ita Luctus Eorum, qui Suis sunt Orbati; By this means the Grief of those, who are depriv’d of their Friends, is alleviated. |Thought more Beneficial to the Living than the Dead.| So that these two Reasons seeming to conduce more to the Benefit of the Living 10than the Dead, it has given occasion to some to believe, that Burial was from thence invented, and of this Opinion was Grotius, who thus writes: Hinc est, quod Officium Sepeliendi, non tam Homini, id est, Personæ, quam Humanitati, id est, Naturæ Humanæ, præstari dicitur; For this Reason it is that the Office of Burial is said not to be paid so much to the Man, viz. To the particular Person, as to Humanity it self, that is, to Human Nature in general. And St. Austin, Lib. 1. De Civit. DEI, cap. 12. and Lib. De Cura pro Mortuis, cap. 2. affirms, Curationem Funeris, Conditionem Sepulturæ, Pompas Exequiarum, magis esse Vivorum Solatia, quam Mortuorum Subsidia; that The regulating and management of the Funeral, the manner of Burial, the Magnificence and Pomp of the Exequies, were devised rather as a Consolation to the Living than any Relief to the Dead. But Seneca, Lib. 1. De Remed. hath more plainly confirm’d both the foregoing Reasons, saying, Non Defunctorum Causa, sed Vivorum inventa est Sepultura, ut Corpora & Visu & Odore fœda submoverentur; Burial was found out not so much for the sake of the Dead as the Living, that by means thereof Bodies noisom both to Sight and Smell might be remov’d: Therefore Andrew Rivet, in his 19th Exercise, on the 23 Chap. of Genesis, commends Sepulture as a laudable Custom, pertaining to common Policy and Honesty. Human Nature would be asham’d to see Man, the Master-Piece of the Creation, left unregarded or lye unburied and naked, expos’d to the Insults of all Creatures, and become a Herritage to the most vile Worms and Serpents, or lye Rotting like Dung upon the face of the Earth; so that if Pity and Compassion will not move our obdurate Hearts to Bury him, the very Stench and Corruption 11of the Dead will compel us to it. Hence Chytræus:

By these two fore-going Causes of Burial appears yet a farther Benefit to Mankind, that they may live without that continual Terror of Death, |Frees from the Terror of Death.| which is occasion’d by seeing such miserable Emblems of Mortality. If you do but consider, when Men at first liv’d dispers’d, the very Abhorrence and Detestation of meeting Dead Bodies, made them to remove such unpleasant Objects out of their sight: Afterwards, when they assembl’d together and built Cities to dwell in, they used Burial for this Reason says Lilius Gyraldus, Lib. De var. Sepult. Ritu. pag. 4. That the Living might not be infected by the most noisom stench of the Dead. The before-going Arguments for Interment have been deduc’d from Natural and Political Reasons, but the latter likewise relating to Physic, and particularly conducing to the Health and long Life of Man (since The Art of Embalming was not known in those Days) we will a little more accurately enquire into the pernicious Effects of Putrefaction, and the fatal Consequences that from thence ensue; for this being the most potent Enemy to Life, |From Putrefaction the Enemy of Life.| Nature is very careful to expel it so soon as ever she perceives, by its odious Scents, its invisible Approaches: Nor can she endure the lesser ill Scents of Sweat or Urine, or those Excrements of 12the Belly, which are necessarily produc’d from the Aliments of the Body, but the Body it self as well as Spirits reject them; for this is to be observ’d, that the Excrements and Putrefactions of all Creatures smell worst and are most offensive to their own Species, which we may see by Cats, which voiding a more than ordinary fetid Dung, always take care to bury it. And such cleanliness of Living renders all Creatures the more Healthful, as we daily find by Birds, Pigeons, Horses, Dogs, &c. which thrive best when their Houses, Stables and Kennels are kept sweetest. There is not only an unhealthy, but oftentimes a secret poysoning Quality in the fetid Odours of a putrid Air, which are made so malignant by Bodies corrupt and exposed therein; and thus, in several Countries, |From the Plague.| great Plagues have been occasion’d only by the Putrefaction of prodigious swarms of dead Grasshoppers and Locusts cast up on heaps. Thus, the Scripture testifies, the Land of Egypt was corrupted with Lice, Flies, Frogs and Locusts as a Punishment to Pharaoh: The Fish of the Rivers died, and the Waters stank; also there was a Murrain among the Beasts, and a Plague of Boils and Blains among the Inhabitants, Exod. chap. 7, 8, 9, 10.

The infectious Atoms of a putrid Air are so very subtile and invisible, that they meet with an easie reception into the Brain and Lungs, as often as we breath, and thereby immediately occasion in the Brain either an Apoplexy or Delirium, a Syncope to the Spirits, a general Convulsion of the Nerves, or else more slowly corrupt the Blood, by mixing with it in its passage thro’ the Lungs, where they either produce Imposthumes, Ulcers, Consumptions or Hectic-Fevers 13which prey upon the Spirits and Vitals, or bring Gangrenes to the extreamest Parts, or the Small-Pox, Purple Fevers, and other malignant Distempers to the whole Body; nay, they too frequently prove the very principal Ingredient of the Plague it self, that inexorable Spirit which so swiftly dispatches many thousands of Souls to the other World.

Thus Poison’d Air, or The Art of Empoisoning by Odours, is more dangerous than Poison’d Water, forasmuch as it is impossible Man should live without Breathing, or subsist in an infectious Air, without a proper Antidote. This Art has been effectually practis’d by the Indians in their Trafficks, and the Turks in their Wars, and was particularly us’d by Emanuel Comnenus towards the Christians, when they pass’d thro’ his Country, in their way to the Holy-Land. This the Lord Bacon relates in the 10th Century of his Natural History, p. 201. where he is of Opinion, That foul Smells, rais’d by Art for Poisoning the Air, consist chiefly of Man’s Flesh or Sweat putrefied, since those Stinks, which the Nostrils immediately abhor and expel, are not the most pernicious, but such as have some similitude with Man’s Body, which thereby the easier insinuate themselves and betray the Spirits. Thus in Agues, Spirits coming from Putrefaction of Humours bred within the Body, extinguish and suffocate the Natural Heat, p. 74. The same effect is likewise to be observ’d in Pestilences, in that the malignity of the infecting Vapour, daunts the principal Spirits, and makes them to fly and leave their Regiment, whereby the Humours, Flesh and Secundary Spirits dissolve and break as it were in an Anarchy, Exper. 333. p. 74.

14Also because the Canibals, in the West-Indies, eat Man’s Flesh, the same Author thought it not improbable, but that the Lues Venerea might owe its Origin to that foul and high Nourishment, since those People were found full of the Pox at their first Discovery, and at this Day the most Mortal Poisons, practis’d by them, |Consists partly of Man’s Flesh, &c.| have a mixture of Man’s Flesh, Fat or Blood. Likewise the Ointments that Witches have us’d, are reported to have been made of the Fat of Children dug out of their Graves; and diverse Sorceresses, as well among the Heathens as Christians, have fed upon Man’s Flesh, to help, as they thought, their wicked Imaginations with high and foul Vapours, Exper. 26. and 859.

The most pernicious Infection, next the Plague or Air Poison’d by Art, is the Smell of a Goal where Prisoners have been long, close and nastily kept, whereof, says the Lord Bacon, we have in our Time had Experience twice or thrice, when both the Judges that sat on the Trials, and numbers of those that assisted, sickn’d on the spot and Died, Exper. 914. The like would frequently befall those that visit Hospitals, and other such Places, where either the Leprosie, French Pox or Malignant Fevers rage, were not the Attendants dayly accustom’d to it, or did they not use proper Antidotes to keep them from it. If therefore the morbid State of the Living only be so pernicious to healthful Bodies, |Air most Infected by a putrid Carcass.| what Destruction must that Air produce, which is replete with the volatile Steams and Spirits, that issue from a dead and putrid Carcass?

For every Thing in Nature easiest Corrupts that of its own kind. The Reason of this is because it is Homogeneal, as is commonly seen in Church-Yards, where they bury much; for a Corps will consume in a far shorter Time there, than it would have done in another place where few have been buried.

It therefore necessarily follows, that if the Dead were not inhum’d, whole Cities would Corrupt and be fill’d with the Plague; and after great Battels, if the Dead should lie unbury’d, whole Countries would be destroy’d; |Sepulture defends from the Plague,| all which Mischiefs are prevented by a timely Sepulture: For the Earth by its weight and closeness not only suppresses and dissipates the Vapours that arise from a putrid Carcass, but also imbibes and sucks up the stinking Gore; and being a Medium between that and the Sun, prevents the Beams of that Planet from suddenly exhaling such fetid Odours. |Likewise preserves Bodies.| Nay the Lord Bacon farther assures us, That Burying in the Earth, which is cold and dry, serves for Preservation, Condensation and Induration of Bodies, as you may find in his 4th Century of his Natural History, Exper. 376, 377. But this needs no farther Confirmation, since Bodies are dug up in every Age perfect and uncorrupt, which perhaps had been buried above 40 or 50 Years, and some have been found petrified to a perfect Stone, of which we shall discourse more hereafter, therefore will at present proceed to acquaint you with other final Causes or Ends of Burial.

16A Third Cause of Burial is, That Man’s Body may not be torn to pieces and devour’d by savage Beasts, and Birds of Prey, which would be a sight wholly unbecoming the Dignity of Human Nature, as Seneca observes Lib. 6. De Beneficiis: Inter maxima Rerum suarum, says he, nihil habet Natura, quo magis glorietur. Nature has nothing in the whole Creation of which she may boast more than of Man: So that it must needs be a grievous Trouble and Concern to her to see the Master-Piece and Perfection of all Creatures become thus a Prey to the vilest of Animals; and that he who whilst living had all of them under Subjection, so soon as ever his Spirit is separated from his Body, they should forget all Allegiance to their late Sovereign, and rebelliously Tear him to Pieces: Therefore we who are his Fellow-Creatures, and endu’d with Humanity, take care to bury him out of the way of such Harpies; and ought to perform all his Funeral Obsequies with the same Respect we were wont to show him whilst alive. Hence Hugo Grotius is of Opinion, That Burial was invented in respect to the Excellency of Man’s Body. |Taken from the Excellency of Man’s Body.| Cum Homo cæteris Animalibus præstet, indignum visum, si ejus Corpore alia Animantia pascerentur, quare inventam Sepulturam, ut id quantum posset, caveretur. Since Man excells all other Creatures, it was thought unworthy they should feed upon his Body; for which reason Sepulture was found out, that this Mischief might be prevented as far as possible. Likewise Lactantius, Lib. 6. Institut. cap. 12. says, Non patiemur Figuram & Figmentum DEI, Feris & Volucribus in Prædam jacere, sed reddamus id Terræ, unde ortum est. Let us not suffer the Image and Workmanship of GOD to lie expos’d as a Prey to the Beasts and Birds, but let us return it back to the Earth from whence it had its Origin.

17So that we will account the Fourth Reason for Burial, to be the Excellency of Man’s Body, to which we ought to show the greater Honour and Respect, in that it is the Receptacle of the Immortal Soul. Hence Origen, Lib. 8. Contra Celsum says, Rationalem Animam honorare didicimus, & hujus Organa Sepulchro honorifice demandare. We have learn’d to Honour the Rational Soul, and respectfully to convey its Organs to the Grave. And thus St. Austin very elegantly expresses himself, Lib. 1. De Civit. DEI, cap. 13. Si Paterna Vestis & Annulus, vel si quid hujusmodi, tanto carius Posteris, quanto erga Parentes Affectus major, nullo modo ipsa spernenda sunt Corpora, quæ utiq; multo familiarius, atq; conjunctius, quam quælibet Indumenta gestamus. If we take so much the more care to preserve our Fathers Apparel, Ring, and other Remainders of the like nature, as we bore an Affection to them, ’tis plain their Bodies are by no means to be neglected, which we wear closer and nearer to us than any Cloaths whatever.

But the Fifth Cause and ultimate End of Burial is in order to a future Resurrection, and as B. Gerhard asserts, agreeable to that Companion of Christ and St. Paul his Apostle, John 12. 24. 1 Corinth. 15. 37, 38. That Bodies are piously to be laid up in the Earth, like to Corn sowed, to confirm the assured Hope of the Resurrection: And therefore the place of Burial was call’d by St. Paul, Seminatio, as others term it Templi Hortus, the Churches Orchard or Garden. By the Greeks it was call’d, Κοιμητήριον, Dormitorium, a Sleeping Place. By the Hebrews, בית חיים, Beth-chajim, i. e. Domus Viventium, the House of the Living, in the same respect as the Germans call Church-Yards, Gotsacker, i. e. DEI Ager, aut Fundus, GOD’s Field, in which the Bodies of the 18Pious are sowed like to Grain or Corn, in expectation of a future Harvest. By these Appellations we are admonish’d of the Resurrection of the Body, and of the Immortality which is given by GOD to the Soul. For as they that Sleep awake again, and as Christ who is the Head arose again, so shall we who are his Members arise. Hence Calvin (Commenting on Isaiah 14. 18.) says, The Carcasses of Beasts are thrown out, because they were Born to Putrefaction; but our Bodies are interr’d in the Earth, and being there deposited, expect the last Day, that they may arise from thence to lead a Blessed and Immortal Life with the Soul. Also Aurelius Prudentius, a Christian Poet, rightly asserts The Hope of the Resurrection to be the chief Cause why the greatest Care is taken of Burial, whereof he has most excellently describ’d every particular Circumstance in a Latin Funeral Hymn, which being Translated by Sir John Beaumont, Baronet, into 172 Verses, I will for brevity sake refer you to Weaver’s Funeral Monuments, pag. 25. where you will find them inserted, and worth your Perusal.

Nevertheless, we are not to think, tho’ Burial was ordain’d by GOD as a Work both pleasing and acceptable to him, and consequently approv’d and practis’d by all Men, that therefore the want of it, or any particular Ceremony thereof, can any ways be prejudicial to a Christian Soul, as St. Austin and Ludovicus Vives his Commentator alledges, Lib. 1. De Civit. DEI, cap. 11. And that Complaint which the Royal Prophet makes, Psalm 79. 3. That there was none to bury the dead Bodies of GOD’s Servants, was spoken rather to intimate their Villany that neglected it, than any Misery to them that underwent it. ’Tis true such Actions may appear heinous and tyranous in the Eye 19of Man, but precious in the Sight of the Lord is the Death of his Saints: Neither is our Faith in his assured Promise so frail, as to think ravenous Beasts or Birds of Prey can any ways make the Body want any part at the Resurrection; but, on the contrary, we are well satisfied that in a Moment there shall be given such a new Restitution, not only out of the Earth, but out of the most minute Particles of all the other Elements, wherein any Bodies can possibly be included, that not a Hair of our Heads shall be missing. We read how the Bodies of the Christians (after great Battels, and the Sacking and Subverting of Towns and Cities) stood in want of the Rights and Ceremonies of Burial, which neither is to be accounted any Omission in the living Christians, who could not perform them, nor any Hurt to the Dead, who could not feel them. We may, moreover, find in the History of Martyrs, and such like Persecutions, how barbarous and cruel Tyrants have raged over the Bodies of Christians, who, not content with tormenting them to Death several thousands of ways, still persever’d with inhumanity to insult over their mangled Corps, and at length to shew their utmost Contempt, bury’d them in the Bowels of rapacious Creatures, or what other ignominious ways their wickedness could invent. Nevertheless, we have all the reason to believe their Souls were receiv’d into Heaven, and that their Bodies will at the last Day be reunited intire to them again; after which, Death will have no more Power over their Bodies than their Souls, but as St. Paul says, 1 Cor. 15. 44. They will become Spiritual Bodies. |Nor any kind thereof hurtful.| So that in this respect it matters not after what manner the Body be destroy’d, dissolv’d 20or bury’d, as Tatian in his Book Contra Gentes says, Quamvis Caro tota Incendio absumatur tamen Materiam evaporatam Mundus excipit, quanquam aut in Fluviis, aut in Mari contabescam, aut Feriis dilanior, condor tamen in Penu locupletis Domini. Altho’ the Flesh be wholly consum’d by Fire, yet the World receives the evaporated Matter, nay, altho’ I am wash’d to nothing in Rivers or Seas, or am devour’d by wild Beasts, yet shall I be reposited in the Store-House of a most wealthy Lord. Likewise Minutius Fælix in Octavio has these Words: Corpus omne sive arescit in Pulverem, sive in Humorem solvitur, vel in Cinerem comprimitur, vel in Nidorem tenuatur, subducitur Bonis, sed DEO Elementorum custodio reservatur. The Body whether it be dry’d into Powder, resolv’d into Moisture, reduc’d to Ashes, or evaporated into Air, is indeed taken away from Good Men, but still the custody of the Elements is reserv’d to GOD. Some have been accounted a rigid sort of Stoicks, and void of all Humanity, for this Reason only, because they averr’d it profited nothing, whether the Body corrupted above or beneath the Earth. Thus Lucan, Lib. 7.

21And that Favorite-Courtier Mecænas was wont to say:

But this these spoke only in respect to the Soul, which could receive no Hurt nor Damage from the Bodies being cast out unbury’d; therefore they seemingly ridicul’d and despis’d it, the better to fortifie Men against any fear of the want of Burial, yet they firmly believ’d that all those who were depriv’d thereof, were the most miserable and wretched of Creatures, and that their Souls continually wander’d, as Virgil elegantly expresses, Æneid. 6. v. 325. where Æneas asking the Cybil why such a number of Souls stood crowding near the Stygian Lake, and were refus’d a Passage, he receiv’d this Answer:

Some again are induc’d perhaps to think the care of Burial needless, because there is no Sense in a Dead Body, as the Proverb has it, Mortui non dolent; and others reject it for this Reason, Quia sentienti Onus est Terra, nihil sentienti, supervacaneum. For the Earth’s a Burthen to him that is sensible of it, but none to him that is not.

Diogenes the Cynic Philosopher, among the rest of his Whimsies, despis’d Sepulture, and when he was told he must thereby become a Prey to the Beasts and Birds, he gave them this jocose Advice, Si id metues, ponite juxta me Bacillum, quo abigam eos. If you fear that, place my Staff by me that I may drive them away. Quid poteris nihil sentiens? What can you do if you are sensible of nothing? Reply’d his Friend. To which he answer’d, Quid igitur Ferarum laniatus oberit nihil sentienti? If I am not sensible, how can their Teeth affect me? At other times he was wont to say on the like Occasion, Si Canes meum lacerabunt Cadaver, Hyrcanorum nactus fuero Sepulturam, Si Vultures, Iberiorum; quod si nullum Animal accederet, ipsum Tempus: Pulcherimam fore Sepulturam, Corpore pretiosissimis Rebus, Sole, inquam & Imbribus absumpto. If the Dogs eat my 23Carcass, I shall have the Sepulture of the Hyrcanians, if Vultures, of the Iberians; but if no Animal come near me, then shall I be consum’d by Time, and, What a fine sort of Burial must that needs be, to have my Body reduc’d to Dust by two of the most precious Things in Nature, the Sun and Showers? Likewise Demonactes being told, if he were flung out unbury’d, as he desir’d, the Dogs would tear him to pieces, he wittily answer’d, Quid incommodi, si mortuus alicui sim usui? What hurt can it do me, if after I am Dead I do somebody Good?

It may farther be ask’d, Why Plato, Aristotle, and other Philosophers, famous for Learning and Piety, despis’d the Rites and Ceremonies of Sepulture? To which I answer, They did not really Despise them, nor durst they say they were not to be at all: They said only, if by chance they were neglected, it could do no hurt. Nor lastly did Lucretius contemn Sepulture, he only laughed at those who procur’d it for this Reason, because they thought there still remain’d a Sense in the Dead, as you will perceive by these Lines of his, Lib. 3.

Hereby ’tis plain Lucretius only blames and chides those who are of a doubtful and wavering Mind, and that openly confess there can be no future Sense remaining after Death, yet privately hope within themselves that some Parts will remain, and therefore mightily dread the want of Burial, nay, violently abhor being a Prey to wild Beasts and Birds. This I take to be a natural hint of the Resurrection of the Body and Immortality of the Soul, tho’ outwardly these Pagans disown’d both:

We cannot believe there were ever any Philosophers 25in the World, of such obdurate Hearts, as strictly to deny Burial, tho’ out of a seeming Arrogance they despis’d it; but that they only pretended so lest their Antagonists should think the want of Burial an inflicted Punishment, therefore they were the easier mov’d, as much as in them lay, to expose them. |Why the Frenchdeny’d it.| Thus Pausanias in Phocic. gives an Instance of some French who deny’d Burial to the slain in Battel, alledging it was a Ceremony nothing to be esteem’d of; but the true Reason they did it was, That they might bring the greater Terror on their Enemies, and make them to have the worse Opinion of their Cruelty. It must be granted, the Dead have no sense of any Change or Dissolution they undergo, and that it is a ridiculous Opinion of Tyrants, to think to punish the Body by mangling it, and delivering it to be torn to pieces and devour’d; neither do Bodies suffer any Hurt or Damage in respect to the Soul, after what manner soever they are bury’d: Yet you must grant these sufficient Reasons why the Dead should be taken care of, and not be despis’d and cast away; for as we esteem the Body the Temple of GOD, and Receptacle of the Soul, so ought we honourably to Interr it with those Funeral Obsequies as are becoming its Quality and Dignity.

Now we must look upon Burial to be a Work enjoin’d both by the Law of Nature and Nations, and not only by the Human but by the Divine Law; for the most Barbarous as well as Civiliz’d People of the World have ever paid some Respect and Observance to their Dead, tho’ perhaps after different Manners, by Burying them in the Water, Earth, Air, Fire, &c. The common Dictates of Nature have taught them to abhor such dismal Objects and offensive Smells as dead 26Bodies must necessarily present, and their Religion has shown them the Inhumanity and Cruelty of neglecting their Duty to them: Nay, if we look into the Natural History of Animals, we shall find some of them excelling Man in this particular, by taking a more than ordinary Care of their Dead, as is to be seen not only in Cranes, Elephants and Dolphins, &c. As Ælian de Animalibus, Lib. 2. cap. 1. and Lib. 12. cap. 6. and Franzius in his History of Animals, cap. 4. Peter Faber in his Semestrium, Pliny and others observe, but likewise in Ants, Bees and other Insects; for as Grotius in his Treatise, De Jure Belli & Pacis, Lib. 11. cap. 19. rightly observes, |Observ’d by Brutes, &c. as well as Men.| Nullum est in Homine Factum laudabile, quin non Vestigium, in alio aliquo Animantium Genere DEUS posuerit. There is nothing done by Man worthy of Commendation, but GOD has imprinted some Imitation of it even in Brutes.

A Corps lying unbury’d and Putrifying, is not only a dismal Aspect to our Eyes, offensive to our Nose, and ungrateful to all our External Senses, but even horrid in our very private Apprehensions and secret Conceptions; nay to hear it but only nam’d, is so very unnatural and unpleasant to us, that we care not to entertain the least Thought of Death, even to the deferr’d Time of our Expiration. What presence of Mind can enable a Fellow-Creature to behold such a miserable Object as this, express’d by its dismal Aspect, deform’d Proportion, fœtid Smell, putrid Carcass, and the like, and this perhaps of one who was but just now your Bosom-Friend or the World’s Favorite, a Prince worthy of Immortality for his Wisdom, Piety, Valour, Conduct, &c. and justly admir’d for the Beauty of his Person, Gracefulness of his Mien, and Conformity 27of all the External Parts of his Body, as well as Internal Qualifications of his Mind? Certainly common Humanity and Self-Preservation would alone persuade us to Inter him out of our Sight, or else preserve him from a State of Corruption and Deformity by Embalming.

I have before observ’d how Beasts receiv’d the Infection of the Murrain from a Putrefaction of their own Bodies; now I will shew you how they likewise, by Natural Instinct, avoid each other in such like Calamities: The Sound shun the Company of the Infected, and they reciprocally separate from the rest to Mourn by themselves. A wounded Bird leaves the Flight: A Stag (when Shot) forsakes the Herd and flies to the Desarts: And every Diseas’d Creature retires into some solitary Place, where its last Care seems to be, that of providing for its Burial. |Every Creature takes care of its own Burial.| Reptiles creep into Holes, and Birds into their Nests, or the Bottoms of thick Hedges: Rabbets die in their Burrows: Foxes, Badgers and Wolves, &c. in their Dens, after which nothing will Inhabit there. So that they seem to know they shall lie undisturb’d in those Dormitories, which they took care in their Lives Time to provide and dig in order to their Interment; like as some Hermits, who, during their Lives, made their Cave their Habitation, but when Dead their Tomb.

The larger sort of Domestic and Tame Creatures seem likewise to endeavour this, as much as they can, as may be observ’d from Horses, Oxen, Sheep, &c. who when they decline and draw near their Deaths, seek either the thickest part of a Wood, a Dell or Gravel-Pit in a Common, or deep Ditch in a Field, where they may lay themselves down, as in a Grave, 28and die: They seem to desire nothing more of their Master, whom they have all their Lives faithfully serv’d, than to cover their Bodies with the Earth.

The lesser Tame Animals, as Dogs, Cats, &c. know they have no occasion to take that Care of themselves, for when they die, their Master is oblig’d to remove them out of his House and bury them: |How Insects bury themselves.| But as for Insects, they (fearing Mankind should be regardless of their inconsiderable Bodies, and not be so grateful as to take care of their Funerals, tho’ they had consum’d their Lives in making Food and Raiment for their Master) seem with a more extraordinary Contrivance, and admirable Art, to provide for their own Burial. The little Bee works its Honey-Comb for the Benefit of Man while it lives, and for its own Sepulture when it dies; the Comb serving for its Tomb, and the Wax and remaining Honey for its Embalment, conformable to that Saying of Martial, in his Fourth Book and Thirty Second Epigram:

The Silk-Worm (which also willingly parts with her Stock and Labour for the Benefit of Mankind) makes a small reserve of Silk, sufficient for her Winding-Sheet, 29which when she has finish’d, she dies therein, and is as nobly Interr’d, as all the Egyptian Art, with its fine Painted Rowlers of Cyprus, Lawn or Silk could make her.

Other Insects, as Flies, Ants, Gnats, and the like, which are not dispos’d with Organs to perform such Works, yet have this in particular, that they can outdare the most resolute Indian |Some are Burn’d and others Embalm’d.| (when, without any previous Exhortation, they suddenly leap into the Funeral Pyre of a Candle or Torch, and outvie the costly Embalming of Arabia) when they voluntarily fly into liquid Amber, and by that means obtain a more noble and incorruptible Sepulture than any other Creature. These have had Poets to write Funeral Orations to their immortal Praise, as the two Epigrams in Martial of a Viper and Pismire in some measure testifie, Lib. 4. Ep. 59. and Lib. 6. Ep. 15. Witness also Brassavolus of the Pismire, and Cardanus’s Mausoleum for a Flie: Nor could Virgil (the Prince of Poets) omit taking notice of the well order’d Funerals of the Bees, Georg. Lib. 4. l. 255.

Ælian, Lib. 5. cap. 49. reports, That if one Elephant finds another dead, he will not pass by ’till he has got together a great heap of Earth and flung it over his 30Carcass; so, in all other Creatures, Nature has provided both Burial and a Grave for them. |Brutes Bury’d with Pomp and Magnificence.| Nay it is yet further remarkable, that such Brutes as have either prov’d faithful or loving to their Masters, or done any extraordinary Action, have been bury’d with wonderful Magnificence, and had Tombs and Inscriptions made in Honour of them. Cimon the Athenian bury’d those Horses he had been thrice a Victor with in the Olympick Games, with great Pomp near his own Sepulchre. Also Alexander the Great made a magnificent Funeral for his Horse Bucephalus, building a City where he dy’d, and calling it after that Beast’s Name in memory of him. After his Example, several of the Roman Emperors and Cæsars, such as Augustus, Caligula, Nero, Adrian, Antoninus, Commodus, &c. bury’d their favourite Horses, and adorn’d their Tombs with Epitaphs, as you may find in Barthius, Lib. 23. cap. 8. Pliny, Lib. 8. cap. 22. Affirms such Horses as had conquer’d at the Olympick Games, were bury’d and had Tombs and Pyramids erected to perpetuate their Fame.

Xantippus carefully bury’d his Dogs, and, as Kornmannus reports, Polliacus erected, in the Garden of Cardinal Urbin at Rome, Columns of the finest Marble, of vast Expence, in Memory of his beloved Bitch, on which he inscrib’d this Epitaph:

2. Alluding to the Dog Days.

Also in the House of that Famous Italian Poet Francis Petrarch, at Arqua, near Padua, there is a Tomb of a Cat, adorn’d with an Elegy, which Santorellus in his Post-Praxis Medica, p. 5. has Printed, with others of a Mule, a Crane, &c. Pliny, Lib. 10. cap. 43. says, a Crow (which imitated Human Voice, and which was wont every Morning to salute the Senators by their Names) was bury’d honourably, being carry’d out on the Shoulders of two Æthiopians, with a Crown before it, and a Trumpet sounding; the Person that kill’d it being ston’d to Death. Ælian, Lib 6. Animal. cap. 7. tells us, Marrhes, King of Egypt, built a Sepulchre for a Raven, which was wont to carry his Letters to and fro under its Wing; and, Lib. 7. cap. 41. he says, Lacydes, a Peripatetic Philosopher, had a Goose which us’d to follow him up and down, both at home and abroad, and whom for that Reason he Bury’d with the same Honour and Respect as he would have done a Brother or Son. The Stag which warr’d against the Trojans, was also honour’d with a Tomb; but it were endless to relate all the Brutes the Pagans have given Burial to, as Rhodiginus witnesses in Antiq. Lect. 58. cap. 13. The Parthians were accustom’d to bury their Horses, and the Molossians their Dogs, as Statius the Poet observes, Lib. 2. Sylvar. in Epicedio Pileti.

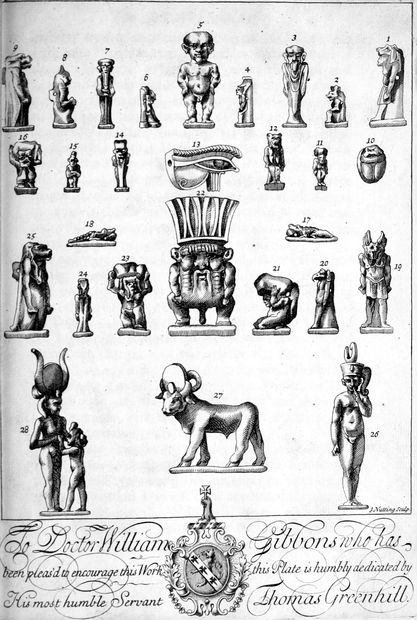

But the Egyptians surpass’d them all, for they Embalm’d the Bodies of several Animals, as Cats, Crocodiles, Hawks and the like, that so they might keep them the longer to adore and admire: If therefore Pagans have been thus careful to honour Brutes with all the Rights of Burial, how much more ought we who are Christians to afford this last Duty to one another?

We find in the first Age of the World, says Cambden, the Care of Burial was so great, that Fathers laid a strict Charge on their Children, concerning translating their Bodies to their Graves, every one being desirous to return in Sepulchra Majorum, into the Sepulchres of his Ancestors. Thus those Holy Patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph and the rest, did not only lay the heaviest Commands about their being bury’d, but also about transferring their Bodies to such Places as they nam’d: So Jacob, at his Death, charg’d his Son Joseph to carry his Body into the Sepulchre of his Fathers, Gen. 47. 30. and 49. 29. And Joseph commanded his Brethren they should remember and tell their Posterity, that when they went away into the Land of Promise, they should carry his Bones along with them, Gen. 50. 25. Now this Filial Care was not only their 33last and greatest Duty to their Parents, |Burial a Work acceptable to GOD.| but also a Work well pleasing and acceptable to GOD; an Example whereof we have in Tobit, who being blind, GOD sent his Angel Raphael to cure him, as a Reward for his pious Care in burying those who had been slain by King Sennacherib in his wrath, and cast without the Walls of Nineveh: But altho’ the King’s Servants forceably took away his Goods, and sought to put him to Death; yet when he heard one more had been strangl’d, and cast out into the Market-Place, he was so zealous in his Care, that tho’ he was just set down to Meat, he tasted not of it, ’till he had fetch’d him up into a private Room, and when the Sun was set, he ventur’d to make a Grave and bury him. |To our Saviour.| Likewise our Saviour (being to rise again the Third Day) commended that good Work of those Religious Women, who pour’d pretious Ointments, with sweet Odours, on his Head and Body, which they did in order to his Burial. Moreover, the Gospel has crown’d those with immortal Praise that took down Christ’s Body from the Cross, and gave it honest and honourable Burial. This signifies, says St. Austin, that the Providence of GOD extends even to the Bodies of the Dead (for he is pleas’d with such good Works) and builds up a Belief of the Resurrection, by which, says he, we may learn this profitable Lesson, viz. How great the Reward of Alms done to the Living must be, since this Duty and Kindness shown even to the Dead is not forgotten of GOD.

Burial of the Dead was accounted by the Antients a Work of Piety and Religion, because they esteem’d it both an Act of Justice and Mercy:

Of Justice, in that Earth should be return’d to Earth 34and Dust to Dust; for, What could be more just than to restore to Mother Earth her Children, that as she had furnish’d them at first with a Material Being, Food, Raiment, Sustenance, and all things necessary, so she might at last receive them again into her Bosom, and afford them lodging ’till the Resurrection? |Of Mercy.| The Antients also thought it an Act of Mercy to hide the Dead in the Earth, that the Organs of such Divine Souls might not be torn and devour’d by wild Beasts, Birds, &c. Cicero in his Oration for Quinctius calls Burial an Act of Humanity. |Of Humanity.| Valerius Maximus, Lib. 5. cap. 1. Humanity and Mildness. Seneca de Benefic. Lib. 5 cap. 20. Humanity and Mercy. Ammianus Marcellinus, Lib. 31. |Of Piety.| A necessary Office of Piety; and St. Ambrose in the beginning of an Oration of his on the Death of the Emperor Theodosius, The last and greatest Office of Piety. Isocrates commending the Athenians for the great Care they took to bury their Dead, says, It was a mark and token of their Piety towards the Gods, since it was they and not Men that had establish’d that Law. Also Servius observes Virgil call’d Æneas by the name of Pious, because of the Funeral Honours, he, with so much Care and Application, had always paid to his Relations and Friends. Plato speaking of the several kinds of Justice, has not omitted what belongs to the Dead; nay Aristotle thought it more just to help those that were depriv’d of Life, than to assist the Living. The Latin Phrase also intimates how just a thing it is to bury the Dead, where it calls Funeral Rites, Justa Exequiarum, or Justa Funebria, quia justum est, justa facere, solvere, peragere. Nay it has no other appellation in that Language than that of Justice, and in Greek of a lawful Custom, Piety and Godliness, so 35that amongst both the Romans and Grecians, who have been the two most potent and civiliz’d Nations of the World, when they would express one had been Interr’d, they said, they had done him Right or Justice, and such as neglected to do the like they accounted void of all Piety and Humanity.

And to shew how Religious an Act it is to bury the Dead; the Gentiles assign’d the Care of all Funerals and Sepulture to certain Gods they term’d Manes, whose chief was Pluto, call’d also Summanus, whence all Tombs and Monuments came to be dedicated, Diis Manibus. Homer, Euripedes, Aristotle and others have accounted Sepulture an Honour and Reward to Mens Actions; and on the contrary look’d on all such as miserable and unhappy whose Bodies lying unbury’d, wanted that last Happiness.

Decent Burial, with suitable Attendants of Kindred and Friends, according to the Quality of the Person (says Weever of Funeral Monuments, p. 25.) is an Honour to the Deceas’d. Hezekiah, says the Text, slept with his Fathers, and they bury’d him in the highest Sepulchres of the Sons of David, and all Judah and the Inhabitants of Jerusalem did him Honour at his Death, 2 Chron. 32. 33. Thus in all Ages Burial has been accounted an Happiness and Quiet to the Mind, and a Favour from GOD, whereas the want of it has been look’d on as an Evil and Misery, a Curse and Punishment, a Disgrace and Ignominy.

First, In the Holy Scripture it is call’d an Happiness, Favour and Kindness: This was foretold by Ahijah, and to be shewn to Abijah, 1 Kings 14. 13. And all Israel shall mourn for him, and bury him; for he only of Jeroboam shall come to the Grave, because in him there is 36found some good Thing towards the Lord GOD of Israel, &c. It was accounted a Glory to be bury’d in a Sepulchre, even to Kings who were laid up in stately Tombs and Monuments, as in their Beds, and thus the Prophet Isaiah speaks, Chap. 14. ver. 18. All the Kings of the Nations lye in Glory, every one in his own House. By the same Prophet GOD comforted Zedekiah King of Judah when he was taken Captive, telling him he should never die in War or Battel, or be deny’d Burial; but that the King of Babylon should give his People leave to bury him in an honourable manner, and with such Solemnities as the burning of sweet Odours, &c. at his Funeral, as they were wont to use at the Exequies of their Kings, who liv’d belov’d of their Country, 2 Chron. 16. 14. But thou shalt die in Peace (says Jeremiah to him, Chap. 34. ver. 5.) and with the Burnings of thy Fathers, the former Kings which were before thee, so shall they burn Odours for thee, and lament thee, &c.

To die a natural Death, to be lamented and bury’d, and to lye in the Sepulchre of their Fathers, was ever accounted a great Honour and Happiness among the antient Jews, for which the Scripture-Phrase, throughout the Old Testament, is Sleeping, which implies lying at Rest and undisturb’d as well as Dying. Thus, in 2 Kings 8. 24. it is said, And Joram slept with his Fathers, and was bury’d with his Fathers in the City of David. And 9. 28. His Servants carry’d Ahaziah in a Chariot to Jerusalem, and bury’d him in a Sepulchre with his Fathers in the City of David. And Cap. 15. ver. 7. So Azariah slept with his Fathers, &c. Also, ver. 22. and 28. of the same Chapter, and in many other places, as 1 Kings 2. 10. So David slept with his Fathers, 37and was bury’d in the City of David. By all this it is to be observ’d, that in this City was the usual Royal Burying-Place, where both David and all his Successors, that were of any Note or Renown, were bury’d. This appears likewise by 1 Kings 11. 43. 2 Chron. 12. 16. and 14. 1. and 16. 14. and 21. 1. David’s Sepulchre was made of such durable Materials, and so well kept and repair’d by his Posterity, that it continu’d ’till the Apostles Time (Acts 2. 22.) which was the space of almost 2000 Years.

On the contrary, to die an unnatural Death, and in another Country, as also to be depriv’d of the Sepulchre of ones Fathers or Ancestors, was always esteem’d a note of Infamy and a kind of Curse. Thus, in 1 Kings 13. 22. the seduc’d Prophet, because he disobey’d the Word of the Lord, was reprov’d by him who was the occasion of his Error, as he had it in Command from GOD, and withal told, That his Carcass should not come into the Sepulchre of his Fathers. Isaiah speaking in derision of the Death and Sepulture of the King of Babylon, which was not with his Fathers, in that his Tyranny was so much abhorr’d, thus notes his Unhappiness, Chap. 14. 19, 20. Thou art cast out of thy Grave, like an abominable Branch; and as the Raiment of those that are slain, thrust thro’ with a Sword; and shall go down to the Stones of the Pit, as a Carcass trodden under Foot. Thou shalt not be join’d with thy Fathers in Burial. That is, he should want all the Honours of Sepulture, and all such Funeral Rites as were to have been paid to him as a most potent King, and that he should not be admitted to lye in the Grave amongst his Ancestors, but that his Corps should remain neglected above Ground unbury’d, and be trodden to pieces like vile Carrion.

38The want of Burial proceeds also from a Judgment of GOD, as will appear from the Example of Jehoiakim, the Son of Josiah King of Judah, whom for his great Wickednesses, such as Covetousness, Oppression, shedding innocent Blood and the like, GOD threatned with the want of Burial (a severe Sentence!) and that he should have no solemn Funeral or honourable Sepulture, such as Kings usually have, nay, not so much as an ordinary Burial among the Graves of the common People, Jer. 26. 23. but be cast out like Carrion in some remote Place: And Chap. 22. 19. |To be bury’d like an Ass.| He shall be bury’d with the Burial of an Ass, drawn and cast forth beyond the Gates of Jerusalem, that is, as an Ass is wont to be bury’d, he being more worthy the Society of Beasts than Men. The Greeks call the Burial of an Ass, ἄταφον τάφον, according to that Expression of Cicero, Insepulta Sepultura; and Sanctius expounds it, that to be bury’d like an Ass, is to be cast out into a sordid and open Place, which neither covers the horrid and obscene Parts of the Body, nor hinders the Dogs or Birds from tearing it to pieces, but as in Chap. 36. ver. 30. His dead Body shall be cast out in the Day-Time to the Heat, and in the Night to the Frost; that being so expos’d, it may the sooner putrefie, and become the more vile and loathsom; and that the sight of a King’s Body, in such a condition, should be an hideous Spectacle and horrid Monument of GOD’s heavy Wrath and Indignation unto all that should behold it, Isaiah 66. 24. Wherefore Ecclesiastes wisely concludes, Chap. 6. 3. A Man had better have never been born than to have no Burial. The People of Israel (crying unto GOD against the barbarous Tyranny of the Babylonians, who spoil’d GOD’s Inheritance, polluted his 39Temple, destroy’d his Religion, and murther’d his Chosen Nation) amongst other Calamities, thus complain for the want of Sepulture, Psal. 79. 2, 3. The dead Bodies of thy Servants have they given to be Meat to the Fowls of the Heavens, the Flesh of thy Saints to the Beasts of the Earth. Their Blood have they shed like to Water round about Jerusalem, and there was none to bury them. Here the Prophet observes, that GOD suffers his Church sometimes to fall to great Extremities, to exercise their Faith before he delivers them; as at other times he deprives the Wicked of Sepulture, to bring them to Repentance by such an ignominious and shameful Punishment. Thus, for the Pride and Wickedness of Jezebel, the Prophet Elijah pronounces GOD’s Vengeance against her, saying, In the Portion of Jezreel shall Dogs eat the Flesh of Jezebel, and her Carcass shall be as Dung upon the face of the Field, so that they shall not say, this is Jezebel, and there shall be none to bury her, 2 Kings 9. 10, 36, 37. |To become like Dung rotting upon the Earth.| By the Comparison to Dung is shown how odious and contemptible a Thing it is to be cast out unbury’d, and to be trodden under Foot, to lye expos’d to the Air and Weather, to rot and stink or become Food to Birds, Beasts and Reptiles. Jeremiah foretelling the Desolation of the Jews, acquaints them, Chap. 19. 7. Thus says the Lord of Hosts, I will cause them to fall by the Sword before their Enemies, and their Carcasses will I give to be Meat to the Fowls of the Heavens, and to the Beasts of the Field, and none shall fright them away, Chap. 7. 33. Deut. 28. 26. Also speaking of their Kings, Princes, Priests and Prophets, he tells them that Their Bones shall be spread before the Sun and Moon, &c. they shall not be bury’d, but be for Dung upon the face of 40the Earth, Jer. 8. 2. In other places of his Prophesie he tells them, They shall die of grievous Deaths and Diseases, they shall be neither bury’d nor lamented, but lye rotting like Dung, and be Meat for the Fowls of the Heavens and Beasts of the Earth, Chap. 16. 4. Chap. 25. 33. Chap. 34. 20. 1 Kings 14. 11. Chap. 21. 23, 24. 2 Kings 9. 10. and Ezek. 29. 4. Also in the 39. Chapter of the Prophet Ezekiel and the 17, 18, 19 and 20 Verses, GOD to shew his severe Judgment, calls the Fowls of the Air and Beasts of the Field to a Sacrifice of the Flesh and Blood of the Princes of the Earth, to eat their Fat and drink their Blood; abundance more Examples of the like nature the Scripture affords us.

Next we will consider what a miserable thing it was esteem’d, even by the Pagans, to lye cast out unbury’d. That disconsolate Mother of Euryalus, is not so much griev’d for the loss of her Son, who was slain in Battel, as for that he should be made a Prey to the Birds and Beasts, whom therefore she thus bewails:

Also the same Poet represents Tarquitus thus insulting over his conquer’d Enemy, Æn. 10. v. 557.

So great was the Honour of Sepulture amongst the Pagans, says Quenstedt, De Sepult. Vet. p. 24. |Sepulture deny’d Enemies out of Revenge.| That when they design’d to shew the greatest Envy and Reproach to their most inveterate Enemies, they depriv’d their Bodies of Sepulture, as is noted in the History of the Heroes in Homer, in the War between Polynices and Eteocles the Theban, and other antient Histories, as likewise in Claudian, De Bello Gild. v. 39. Now Mezentius fearing this, does not desire Æneas to spare his Life, but earnestly entreats him to afford him Burial, Virg. Æneid, Lib. 10. v. 901.

Turnus also intreats the like Favour:

However, generally speaking, Sepulture was observ’d as well in Time of War as Peace, to which purpose Heralds or Embassadors were wont to be sent to make Truce ’till they could bury their Dead; which if deny’d, says Grotius, the Antients thought their War more lawful and just. Thus Hannibal, a sworn Enemy to the very Name of Romans, is said by Livy, Decad. 3. Lib. 2. to have sought the Bodies of Caius Flaminius, Tiberius Gracchus and Marcellus Roman Generals, conquer’d and slain by him, that he might bury them. Likewise Philip of Macedon is equally to be commended for his Humanity, in performing Funeral Rites and Ceremonies towards his deceas’d Enemies; of which see Peter Faber, Lib. 3. Semestr. cap. 13. p. 183. who also gives the like account of his Son Alexander, in that after he had overcome Darius, he granted leave to his Mother to bury him after what manner she pleas’d, and withal commanded the same Honour to be afforded the Persian Nobles; as also that all such Soldiers as were found slain should be bury’d with care, as is recorded by Q. Curtius, Lib. 3. Valerius Maximus likewise, Lib. 9. cap. 8. tells us the Athenians so strictly observ’d this Custom in their Wars, |Generals put to Death for neglecting it.| that they punish’d those Generals with Death that neglected to bury the Slain, tho’ otherwise they were Men of Valour and had done several extraordinary Exploits. |Others have perform’d it with great Care.| Plutarch in his Lives, informs us how careful Nicias, an Athenian General, was in this point, for he commanded his whole Army to halt, while he honour’d 43two slain Soldiers with Burial and a Tomb. The like pious Care is mention’d of Æneas to Misenus, by Virgil in his 6th Æneid, v. 232.

The Romans in general as well as the Grecians carefully bury’d their Enemies, nor would they defraud them of any Funeral Rites, says Suidas. The like Rhodiginus, Lect. Antiq. Lib. 17. testifies of the Hebrews, by whose Law the Enemy was not to be left unbury’d. Nor must we pass by the Humanity of the Northern People, who as Olaus Wormius in Monument. Danic. Lib. 1. cap. 6. writes, thought it deserving the greatest Praise, to exercise this Hospitable Piety of burying the Carcasses of their Enemies, to whom they bore no farther Malice after their Deaths, but afforded them friendly Sepulture. Amongst others, an Example of this nature is fetch’d out of Saxo, a most eloquent Danish Historian, who in the Third Book of his History, which he wrote about 500 Years ago, introduces Collerus pronouncing this wise and elegant Oration to his Enemy Horvendillus, with whom he was going to engage in Fight:

Quoniam, says he, Exitus in dubio manet, invicem Humanitati deferendum est, nec adeo Ingeniis indulgendum, ut Extrema negligantur Officia. Odium in Animis est adsit tamen Pietas, quæ Rigori demum opportuna succedat, 44nam etsi Mentium nos Discrimina separant, Naturæ tamen Jura conciliant. Horum quippe Consortio jungimur, quantuscunq; Animos Livor dissociet. Hæc itaque Pietatis nobis Conditio sit, ut Victum Victor Exequiis prosequatur. His enim suprema Humanitatis Officia inesse constat, quæ nemo Pius abhorruit. Utraq; Acies id Munus, Rigore deposito concorditer exequatur. Facesset post Fatum Livor, Simultasq; Funere sopiatur. Absit nobis tantæ Crudelitatis Specimen, ut quanquam Vivis Odium intercesserit, Alter alterius Cineres persequatur. Gloriosum Victori erit, si Victi Funus magnifice duxerit; nam qui defuncto Hosti Justa persolverit, superstitis sibi Favorem adsciscit, vivumq; Beneficiis vincit, quisquis extincto Studium Humanitatis impendet. Which may be thus English’d: By reason the Event of what we are going about is doubtfull, let us mutually engage to shew Humanity to each other, nor so far indulge our Passions as to neglect the last Duties. We have Malice in our Hearts, let there be likewise such a Piety as may opportunely succeed our Rigour; for tho’ a difference in our Minds happens to divide us, the Law of Nature will reunite us. Tho’ we are never so far seperated by Envy, this will bring us together again. Let it therefore be the Condition of our Piety, that the Conqueror follow the Herse of the Conquer’d. Herein the last Offices of Humanity consist, which no good Man ever yet refus’d. Let both Armies then suspend their Hatred to perform this Duty. After Death let Envy be remov’d and secret Prejudice disarm’d. May every kind of Cruelty forsake us, tho’ living we hated each other, let us lovingly accompany one anothers Ashes. ’Twill be a Glorious Thing in the Victor Magnificently to Interr the Vanquish’d; for he that performs Funeral Rites to a slain Enemy, will be sure to have a surviving Friend, and 45whoever employs his Study in Humanity towards the Dead, cannot thereby fail of obliging the Living.