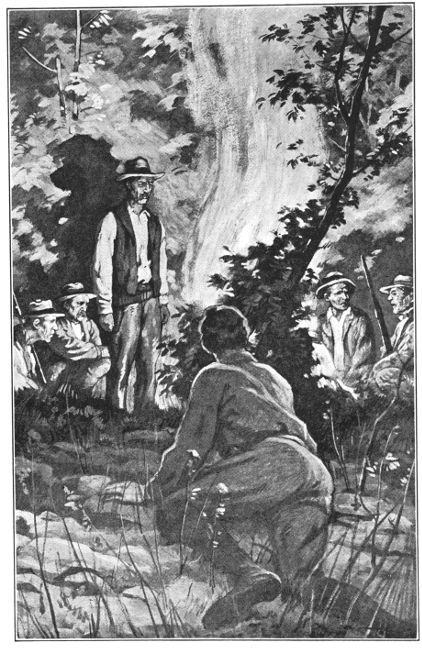

“WE’VE GOT TO GET ’EM, I TELL YOU.”

Project Gutenberg's Scott Burton and the Timber Thieves, by Edward G. Cheyney This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Scott Burton and the Timber Thieves Author: Edward G. Cheyney Release Date: May 12, 2018 [EBook #57147] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TIMBER THIEVES *** Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

“WE’VE GOT TO GET ’EM, I TELL YOU.”

Scott Burton sat on the porch of the little cabin on the edge of the forest and looked absently out across the wide beach at the restless waters of the Gulf of Mexico. No one ever would have guessed from his expression now how crazy he had been to see that gulf only the day before. He apparently did not see the water at all. The big waves boomed on the beach unheard and even the little oyster schooner, which glided across the picture on its way to port, failed to catch his attention. He had sat motionless for so long that a great big fox-squirrel, afraid but drawn on irresistibly by his curiosity, had crept nervously up within a few feet of him.

Suddenly Scott shook his head to rid himself of a bothersome fly and the frightened chatter of the squirrel as it whisked behind the nearest tree broke the spell. He gave the intruder a quick glance and turned his attention once more to the open letter which he held in his hand. He had read that letter dozens of times, in fact he knew every word on the typewritten page by heart, but he read it again now in the hope of finding some additional meaning between the lines.

“Your remarkable work in cleaning up the trouble with the sheepmen on the Cormorant Forest last summer has led us to select you for some special work of a rather delicate character on the Okalatchee. There have been some timber thieves at work on that forest for some time, and so far our officers have been unable to catch them or effectually put a stop to their work. It will be your particular duty to see that these thefts are stopped and the trespassers brought to justice.

“In order that you may have ample authority, you have been appointed deputy supervisor under Mr. Graham and will be given every possible assistance.

“You will report directly to this office.

No, he could not see any more in it, and yet it seemed mighty little to tell a man who had been looking forward to that letter for a week and had traveled two thousand miles to get it. He turned the paper over thoughtfully as though he hoped to find some further instructions on the back of it, and then proceeded to review once more the whole situation.

He had been fortunate enough to earn considerable distinction in Arizona, where he had been working as a patrolman, by clearing out a gang of grafters who had been running sheep on the Forest without a permit. This achievement had won for him the chance of an appointment as a ranger, but he had asked for the opportunity to obtain a little more experience as a patrolman before taking up a more responsible position. His request had been granted and he had spent the summer very profitably on the district he had cleaned up so creditably in the spring.

Suddenly, without the slightest warning, he had received a telegram from the Washington office.

“Report Okalatchee, Fla., at once. You will find instructions there.”

He had become attached to the Southwest and had looked forward contentedly to a permanent location there, but he was possessed of even more than the usual young man’s love of travel, and Florida had always been a country of his dreams, a country of fairy tales that he had hardly even dared hope to see. The sudden realization that he was actually going there had driven everything else from his mind, and an hour after he had received the message he was in the saddle on his way to town.

It was only when he was on the train speeding across the vast expanse of Texas, with plenty of opportunity to think, that he had begun to burn with a consuming curiosity to know what his instructions would be. The longer he had traveled the higher his air castles had grown and the more anxious he had become to see those instructions. By the time he had reached New Orleans he was in such a hurry that he could hardly enjoy his ten-hour wait there, though it was the first southern city he had ever been in and a place which he had always longed to see.

The sight of the tall palmetto palms and the moss-covered live oaks drove his imagination to even more fantastic efforts, and finally arrived in Okalatchee he had almost run directly from the train to the postoffice to get those precious instructions. And this letter was all that he had found. He had found that the supervisor’s headquarters were five miles away through the pine woods and the telephone gave him no answer. He had hired an old negro to drive him over. There was no one there, but the door was not locked and he had decided to stay there till some one came. He was not much better off than before he had obtained the letter.

“Well,” Scott thought, “there is nothing to do but wait till the supervisor turns up,” and he proceeded to investigate his new surroundings.

The little three-room cabin, built of rough lumber with battens over the cracks, was exactly like numbers of other ranger cabins he had seen, but its location had been selected with more than the usual attention to beauty and comfort. It nestled just within the edge of a very dense stand of tall, longleaf pines and the little front yard ran out to meet the broad sand beach. Flowerbeds of hibiscus and groups of oleanders lined the walk of crushed oyster shells, and plants with which Scott was entirely unfamiliar were scattered around in great profusion on either side of the cabin. It seemed to Scott as though a woman must have planned it all, for he could not imagine a man taking so much pains with the decoration of his home. He found himself thinking that it was no wonder this fellow had not caught the timber thieves.

Just to the west of the cabin a little creek bordered with titi and sweet jasmine wandered slowly out to meet the blue waters of the Gulf. It could not always have flowed as slowly as it did now, for some time in the past it had built quite a little delta which extended out in the form of a miniature cape, and was covered with a grove of tall, stately palmettos. Far out from the shore a long line of low-lying sand islands broke the horizon. It was certainly an ideal spot.

The interior of the cabin was quite as tastily equipped as the exterior, and the cupboard seemed to be stocked for a long siege. There was nothing lacking even to the luxuries. Scott smiled as he thought of his own bare little shack high up in the southern Rockies with the round bullet hole in the windowpane.

“I don’t care if that sissy supervisor does not show up for a week,” Scott grunted contentedly as he settled down in a comfortable steamer chair on the porch. No one could have asked for a better place to wait. But Scott was not much given to idle comfort, especially when his curiosity was aroused, and it usually was aroused about something. Just now he was almost wild to know something more of this new problem which he had been given to solve. He watched a little flock of sandpipers run along the smooth beach a way, following the very edge of a wave, but long before they had turned the point of the little palmetto cape he jumped restlessly from the chair and went into the cabin to study a map which he had noticed hanging on the wall.

It was a detailed map, showing the irregular boundary of Okalatchee forest and the different types of timber. It was a great sprawling tract of a million acres extending along the gulf to the river on the west, to the farm lands on the east, and north to the big swamp. It was covered with unfamiliar terms he had seen in books, but which had never seemed real to him before. He had always read them before as he would read the names in a fairy tale, and here he was in the very midst of them: pine ridge and cypress swamp, hardwood bottom and gum slough, low hammock and baygall, high hammock and cane break, turpentine orchards and stills.

He marveled at the great number of ridges shown in that flat country, and the many long, stringlike swamps which paralleled the river and the coast. And he wondered where in all that maze of unknown country the timber thieves whom he was supposed to catch were working. He noted several ranger stations shown on the map and wondered whether any of them were connected with the mystery as had been the case in the sheep business in the West, or whether there were really any thieves at all. He remembered reading a story in which men had been convicted on circumstantial evidence of stealing a raft of logs, and it was not till they had served a month in jail that the raft had been found in the bottom of the pond where it had been tied.

If only the supervisor, or any one else who could tell him anything about it, would come. He had not liked the “gum-shoe” game as he had called it when he had been obliged to try his hand at it in the West, but he found himself eager to get at it here because other men had tried it and failed. It seemed to him like a challenge and he was eager to accept it.

He pored over the map, studying the lay of the land and letting his imagination run wild. He had caught those thieves in forty different ways in at least a dozen different parts of the map when the failing light warned him that it was time to get supper and prepare for the night.

He had no instructions or invitation to make use of that cabin or the supplies in it, but there is a certain freemasonry among the men of the woods which was invitation enough for him. He had no hesitation in spreading his blankets on one of the beds and ransacking the cupboard for his supper. There was plenty to choose from and the wood was laid in the stove ready for the match. In half an hour he was sitting down to his lonely meal.

But it was not destined to be a lonely meal. Scott had hardly finished what he probably would have called his “first course,” when he heard a light step on the shell walk, a thud or two on the porch, and a man loomed big in the doorway.

Scott’s first impression was that this was the biggest man he had ever seen. He almost filled the doorway and the crown of his Stetson brushed the frame. His keen eye took in the interior of the cabin in one swift glance as he entered and then focused steadily on Scott, who had risen smiling to greet him.

“Mr. Burton, I presume?” he said, smiling pleasantly and extending a cordial hand. “My name is Graham. Glad to see you.”

“I am afraid that I am trespassing on your property, your provisions and your good nature,” Scott explained, “but I did not know what else to do.”

“Wasn’t anything else to do,” Mr. Graham said as he hung his hat carefully on a nail. “If you have just cooked supper enough for three I shall not say a word.”

Scott involuntarily glanced toward the door.

Mr. Graham noticed the look. “Oh, there isn’t anybody with me,” he laughed, “that’s just the way I feel. Had lunch with a cracker to-day. Maybe you don’t know what that means yet, but you soon will.”

“Well, I wasn’t expecting two men to supper,” Scott laughed, “but I think there is plenty for all three of us.”

Scott started to get another cup and plate, but Mr. Graham had already gotten them for himself and took the seat opposite. He had never seen a man who looked more like his ideal of a woodsman, or one whom he had liked better at first sight. They had not been together five minutes and yet Scott felt as though he had known this big man for months.

“I had word from Washington that you would be down here,” Mr. Graham explained, “but I did not know just when you would come. I had a trip to make and thought I would get it in before you arrived. Found out at the postoffice that you had beaten me to it. What do you think of my hang-out here?”

“It’s a wonder!” Scott exclaimed enthusiastically. “I was just thinking before you came that I would not mind waiting here for you for a week or two.”

Mr. Graham was evidently pleased with his enthusiasm. “Don’t blame you, I feel pretty much that way myself. I ran on to it by chance one time and it took my fancy so that I decided to fix it up for my summer headquarters. I like it so well now that I stay here nearly all the time.”

“You fixed it up?” Scott exclaimed incredulously.

“Sure,” the big fellow grinned, immediately divining his thoughts. “Thought some woman did it, did you?”

Scott admitted it rather sheepishly.

“Yes,” Mr. Graham confessed, “I am somewhat of a lady myself when it comes to a love of flowers and beauty. I dawdle around out there in the yard a good share of my spare time. Not many ‘movies’ around here to distract a fellow’s attention.”

And so they talked till the meal was finished, the dishes washed, and the dishrag hung on its proper nail; for Mr. Graham was as orderly in the house as he was in the yard. Then they settled down in the steamer chairs on the porch and gazed in silence for a few minutes at the line of islands shimmering in the moonlit bay. It was like a scene from a fairy tale.

Mr. Graham broke the spell with a sigh. “I could look at a thing like that all night, but I suppose you are burning up to know something of this peculiar job to which they have assigned you.”

Scott admitted that he was rather curious.

“Well, I’ll try to tell you the whole story. The trouble started about two years ago. The Quiller Lumber Company had bought a big bunch of pine and cypress timber up near the edge of the big swamp. They are a small concern and do not have a very large crew. Of course, that means slow work and easy checking for us. Their slowness came to be a standing joke with the ranger up there who looks after the scaling. He used to say in his diary every now and then, ‘Quiller got down another tree to-day.’

“They had been at it about six months when the foreman came down to see me. ‘Have you noticed anything peculiar about our scale?’ he asked. ‘Noticed there has not been much to scale,’ I told him. ‘That’s just it,’ he said, ‘checked up on the stumps any?’ I explained to him that we seldom did that till a considerable quantity had been cut.

“‘Well, I have,’ he said, ‘and more than half of the stuff we have cut ain’t there.’

“He went on to tell me that he had had a night watchman on the boom for two weeks and tried in every way to check the thing up, but the logs kept disappearing just the same. A lot of his niggers got superstitious about it and quit the job.”

“How do they handle their logs?” Scott asked.

“Skid them down to the edge of the big swamp on high wheels and shove them into a bag boom. Then they raft them and float them out into the river.”

“Do they keep them in the boom long?” Scott was thinking again of the story of the sunken logs.

“Oh, they are not in the bottom of the swamp if that is what you are driving at. Murphy has prodded the bottom of that pond with a pike pole a dozen times.”

“Is there a channel through to the river or can they take them out anywhere?”

“I’ve hunted all over there myself and I cannot find a place where they could take them out except through that one channel.”

“I suppose you have had that channel watched?”

“Watched, I had Murphy hidden up there on a point of land for a month and the logs disappeared out of the boom right along just the same.”

“Are you sure that Murphy is all right?”

“Murphy, why, he thinks more of the Service than the Secretary of Agriculture does. No, sir, it is not graft, I am sure of that; but I would give a good deal to know what it is.”

“Do they disappear before or after you scale them?”

“Did go both before and after. We scale them all in the woods now before they put them in the boom, but they are going out of the boom just the same.”

There was a long pause while both men frowned unseeing across the beautiful lagoon. Scott was thinking of the ranger who had been the leader of the sheep gang in the West and wondering how he could best get a check on Murphy. Mr. Graham had long ago gotten past the point where he could think about it logically at all.

“Has the thing been going on ever since?” Scott asked.

“For two solid years,” Mr. Graham answered peevishly. “I have put about half my time on the pesky thing and Murphy hangs around there like a baited bulldog. The foreman is almost crazy about it. He has all but accused the ‘’gators’ of eating the logs.”

“I suppose they take some rafts out occasionally?”

“Sure. They have been taking them out right along. Have speeded up considerably during the past year.”

“Ever check up the delivery of those logs?”

“Many a time, and so has the company. Check to the dot with the scale in the rafts.”

“If you are scaling in the woods you are getting paid for all they cut, aren’t you?”

“Yes, the company is paying all right. They howl and checkscale a lot, but they pay.”

“Then why is the Service interested in it? They are not losing anything by it.”

“No, they are not losing anything on this scale, but it is hurting our other sales and giving the forest a bad name. We do not like to have a thing like that going on under our very noses. Besides, it gets on a fellow’s nerves. I tried my best on it. Hated to give it up, but had to confess myself licked at last. Then I asked the office for help and you are the result.”

“Some result,” Scott grunted. “I am not a professional detective. I just stumbled on to that sheep graft out there by chance, and now look what it’s gotten me into. I had never been to Florida and was glad enough to come down, but there is a fat chance of my solving this mess. It looks about as clear as mud.”

“That’s about the way it looks to me,” Mr. Graham nodded, “about as clear as mud. But all of us here are hypnotized now. We have been mooning over the thing so long that we cannot see straight any more. We may be walking all over some clue which will be perfectly clear to a stranger with an unfogged mind. Don’t give up before you start, man.”

“I’m not giving up,” Scott exclaimed, “far from it. Now that I have come all the way down here I simply have to put the job through, but I’m going to steer clear of these detective jobs in the future. They are too uncertain. Too much depends on luck.”

“Well, here’s wishing you luck,” said Mr. Graham, rising; “we’ll give you all the help we can, and grunt for you. Let’s go to bed, and to-morrow we’ll ride out and have a look at the arena.” He paused for a moment at the porch railing. “Isn’t that fine? You can just imagine old Ponce de Léon threading his way along that beach looking for the Fountain of Youth four hundred years ago, and I’ll bet he stopped and sampled that very creek.”

This historical touch gave the country a new interest to Scott.

Scott and Mr. Graham had an early breakfast together.

“I suppose there is no use in asking a man from the West if he rides?” Mr. Graham laughed.

“Not much,” Scott replied. “If a man lives in that country he has to ride. It almost broke my heart to leave my saddle horse behind, but the ‘super’ there seemed to think that I would be transferred West again and would not be here long enough to make it worth while to ship him East.”

“Humph,” Mr. Graham growled, “judging from my own experience you will be grayheaded before you catch those thieves. Well, I have two ponies here and you can use one of them. He’s not the best in the world, but I guess he’ll do.”

Scott was glad to find the western stock saddle in use here instead of the English saddle he had been used to in his home in Massachusetts. The man who has once become familiar with a stock saddle wants no other. The pony, too, though far from the equal of the big black stallion he had bought from Jed Clark, was a very good one. It was easy to see that Mr. Graham was a connoisseur in more things than cabin sites and flowerbeds. Everything he owned was of the best.

“We’ll take a run up around the cuttings first,” Mr. Graham explained, “have lunch at the turpentine camp, and come back by the river. That will give you a pretty good idea of the whole forest and show you just how the land lies. Then you can study the thing in detail at your leisure and tackle it any way you please. I’ll help you all I can but I have failed at it too often to have any advice to offer.”

“I’ll probably need all the advice I can get whether it is any good or not. I certainly have no ideas about it now, but there cannot be much wrong with seeing the country first.”

Their road—it was little more than some winding wheel tracks—lead through a rather thin stand of tall, yellow pines which were straight and smooth as telegraph poles with only a few flat branches near the top. In places there was scarcely any underbrush on the ground, only a few stray spears of wire grass and a thin layer of dead needles which scarcely covered the white sand. Here and there were large patches of scrub palmetto, just leaves three or four feet high growing up from the snakelike roots which seemed to lie almost on the surface of the ground. With the exception of these palmettoes it did not look very different from the pine forests of the Southwest with which Scott was so familiar.

“Where are all those ridges which are marked on the map hereabouts?” Scott asked, as he looked curiously at the level country. So far he had seen no sign of a hill.

“There is one of them,” Mr. Graham laughed. “Doesn’t look much like the ‘Great Divide,’ does it?”

“I don’t get you,” Scott said, still scanning the country.

“Well, you see this country is all made up of strips of swamp and strips of dry land. The dry land is often not more than two or three feet higher than the swamp, but it is called a ridge just the same. Must seem a little strange to a man from the mountains.”

Just ahead of them appeared a solid bank of dense underbrush, all woven together with climbing vines which arched the road like a gateway. The road dipped slightly under the arch where the ground was black and damp, but rose quickly and was almost immediately out in the open pine woods again.

“That,” Mr. Graham explained, “is a baygall, and this is another ridge. Always be careful how you try to ride through those baygalls where there is no road, they are sometimes very soft and even if they are not you are more than apt to hang yourself in those vines. They have yanked me out of the saddle more than once.”

For two hours they rode through this fascinating country of alternating swamp and pine flats without seeing any one or any sign of human habitation. It seemed to Scott even more deserted than his own wild, rocky mountains. They ducked through a little baygall and suddenly came out on to an open ridge from which all the timber had been cut. A more desolate-looking place Scott had seldom seen. Every stick of timber was gone and under the Forest Service regulations the slashings had been burned so clean that the ground was perfectly bare. The low stumps stood out like tombstones in a cemetery.

“You are approaching the haunted grounds now!” exclaimed Mr. Graham. “This is where Qualley is cutting and over yonder in that swamp lies the enchanted pool where all those logs have so mysteriously disappeared.”

They could hear the sound of axes now and the darkies laughing and shouting at the mules. Soon they overtook the strangest-looking rig that Scott had ever seen. It looked at first like two great wheels rolling along the road alone, but as they drew closer he could make out a pair of mules ahead of them and three long logs hung on chains underneath. He had read of these “high wheels” (they were actually eight feet high), but these were the first he had ever seen. A darky was sitting on the long tongue singing light-heartedly and punctuating his song with entirely unnecessary shouts at the patient mules. When he saw the riders his shiny black face broke into a broad grin.

“Whatever crooked work is going on around here,” Mr. Graham remarked soberly, “these darkies are not in on it. They are always as jovial in their welcome as that fellow there and they are scared to death of this pond.”

“Or they are good actors,” Scott said. He was unwilling to except any one from his suspicion.

Mr. Graham shook his head. “Of course, you are right to suspect everybody. I was just expressing my own convictions. A white man can act scared pretty well but when a nigger turns gray he is scared.”

A little farther on the logging road ended abruptly at a rough log dock on the edge of a pond. It was unlike any other log pond which Scott had ever seen. It was in reality an arm of the big cypress swamp. Great churn-butted cypress trees rose queerly out of the water around it’s edges. They were bare of leaves, but their limbs were draped with great festoons of Spanish moss. A number of long pine logs, some loose and some bound together into rafts, floated quietly on the black waters. Around the head of the pond directly opposite them and back a way from the water were the crude board shacks of the logging crew.

It was a dull, gray day and the whole scene presented a gloomy enough picture.

“So this is the haunted pond?” Scott asked eagerly, as he took in every detail of the surroundings. “It sure looks it to-day.”

“Yes, this is the place, but it has had me baffled for so long now that I am not sure whether it is haunted or enchanted. Seems sometimes as though it must be enchanted.”

They sat their horses and gazed at the pond in silence for several minutes. Mr. Graham had stopped even thinking about the possible solution. Scott was studying all the details of the layout. This was the place where his problem must be solved and he wanted to be familiar with every foot of it.

“What’s that?” he asked suddenly, pointing at a bunch of brush near the opposite side of the pond.

Mr. Graham studied the clump carefully and made out the outline of a man half screened by the foliage. Even as they looked the form melted away.

“Come on!” Scott called as he spurred forward. “Let’s ride around there and see who that is.”

They dashed wildly around the end of the pond on the trail which the logging teams had made. It could not have been much more than a minute till they had reached the point opposite the clump. There was thirty feet of water between it and the shore, and it was screened quite as thoroughly on this side as on the other. They examined it minutely but found no sign of life.

“You stay here and watch it while I go get a boat,” Mr. Graham suggested. He rode back toward the shanties and Scott kept his eyes glued on the spot where he had seen that mysterious figure.

Before Mr. Graham had ridden fifty yards a shrill whistle arrested him. Scott turned quickly at the sound and saw a man walking leisurely toward him along the edge of the swamp. Mr. Graham rode back again to join them.

“Thought you had him that time, didn’t you?” grinned the newcomer.

“Sure did,” replied Mr. Graham good-naturedly. “Was that you out there on that stump?”

The man grinned again and nodded. Scott thought that he looked a little ashamed of his discovery and studied him suspiciously.

“What made you beat it when you saw that we had spotted you?”

“Well, I did not want to wave because I did not want those other fellows to know that I was there. I knew you’d come whooping around here to have a close look, so I slipped out and came along the shore to meet you.”

“Pardon me,” exclaimed Mr. Graham, noting the curious glances the two men were casting at each other. “I had forgotten my manners. Murphy, this is Mr. Burton who has been sent down here by the office to solve this log-stealing mystery. Murphy is the ranger in this district,” he explained to Scott, “and can probably tell you more about this thing than anybody else.”

The two men shook hands and Scott found himself looking into a pair of clear, blue, unfaltering eyes.

“I ought to be able to tell you something about it,” the ranger admitted doggedly, “but I can’t tell you a blamed thing. I’ve sat on that stump out there till I’ve worn it smooth, but I have not found out a thing. Not a single thing.”

“Ever watched at night?” Scott asked.

“Day and night,” he replied. “Watched out there all one night without seeing so much as a bubble on the water, and in the morning Qualley reported another bunch of logs missing. Gone right from under my nose.”

Scott looked mystified but said nothing.

“I’m showing Mr. Burton the layout to-day and letting him get the general run of things. Going over to the turpentine camp for lunch and have to keep moving. You will help him all you can if he wants you.”

“You bet I will!” Murphy exclaimed enthusiastically. “I’ve had my try at it. Now I’d like to see how somebody else goes about it. Call on me any old time,” he called to them as they rode away.

“Funny place for him to be,” Scott commented after a long silence.

“The thing is getting on Murphy’s nerves,” Mr. Graham laughed. “It would not surprise me much to find him in the bottom of that pond in a diving suit. He wakes up in the middle of the night and sneaks over there.”

Scott did not say any more about it, but he decided to keep his eye on Murphy. There might be more than one explanation of his interest. At least he would bear watching. They rode in silence for some time, each absorbed in his own thoughts. All traces of the big swamp were far behind them and they were once more on the open pine ridges.

At first Scott did not notice any difference between this forest and the one they had traversed earlier in the day; he was too busy thinking of that enchanted pond, but he soon realized that there was a difference. There was a little earthen flowerpot hanging near the ground on the side of each tree. On some of the larger ones there were three or four of them. For three or four inches above each cup the tree was scratched as though some great bear had been sharpening his claws there. These scratches were very regular and there was exactly the same number above each cup. At the bottom of the scratches and draining into the flowerpots were two little tin gutters stuck into slits in the tree.

Scott knew that they must be in the turpentine orchard. It was the first one he had ever seen. He was very curious to know all about it, but he did not want to appear too ignorant. “Is this a very large orchard?” he asked.

“About twenty crops,” Mr. Graham answered absently.

That meant over two hundred thousand cups and it seemed to Scott like an enormous number. It did not seem possible to take care of so many. It was not long till they saw a darky in overalls and undershirt shambling about from tree to tree.

“Ever seen them chip?” Mr. Graham asked, suddenly realizing that it must all be entirely new to Scott. Scott admitted that he had not.

“They are pretty clever at it,” Mr. Graham continued, riding over to the darky, who greeted them with a pleased grin. “Show us a good one now, Josh. This gentleman has never seen it done.”

There is nothing that a darky likes better than showing off an accomplishment to a stranger. He was carrying a heavy iron, weighted with a ball at the lower end and bent into a loop of sharpened steel at the top. He gave this instrument a fantastic flourish, leaned down over a cup, and with a few deft strokes cut a new scratch in the outer wood of the tree, perfectly straight and overlapping just a little the streak below it. He repeated the operation on the other side of the cup and straightened up with another grin.

“Pretty good!” Mr. Graham exclaimed approvingly.

“Couldn’t beat dat one, boss,” replied the darky with a chuckle.

“Been over to the pond lately, Josh?”

“Who, me? No, suh, you don’t ketch dis heah niggah hangin’ roun’ deah. Dat eah place hanted, boss, sho nuf hanted. Dey tell me you kin put a log in de watah deah and see it ’solve smack befo’ yo’ eyes.” And his own eyes rolled strangely and showed a broad expanse of white.

“Sounds bad,” said Mr. Graham, laughing as he turned to ride away. “No danger of his stealing any logs out of there,” he remarked to Scott when they were out of hearing. “Looked easy enough to see him cut that streak, didn’t it? Try it yourself once. It would take you ten minutes and then it would look like beaver work. That man has to make the rounds of his crop every week; over three thousand streaks a day.”

Just twenty men were putting two streaks a week over each one of those two hundred thousand cups. It seemed marvelous to Scott. In another place he saw a man with a large wooden bucket and a paddle going from tree to tree, emptying the cups. He emptied his bucket into barrels beside the road and a wagon collected the barrels. Scott could not help thinking what a glorious fire there would be if it ever got started in all that resin.

Before long they came in sight of a group of rough board buildings strung along the road like the main street of a small town.

“That,” Mr. Graham explained, “is the still. The darkies and their families live in those little board shacks pretty much as they used to in slavery days. The company keeps a store here for them, the superintendent lives in that house next to the store and the still is down at the other end of the street. It’s quite a town. They will use this camp for their turpentine operations for thirteen years and then log for three years more.”

Slovenly negro women, many of the older ones smoking pipes, gazed at them from the doorways, and shiny black pickaninnies rolled the whites of their eyes in awed attention as they passed. Near the store they met Mr. Roberts, the superintendent, coming home to dinner. He acknowledged Scott’s introduction very effusively and promptly invited them both in to dinner. His wife was of the cracker type and looked old at thirty-five.

In spite of the man’s cordiality Scott did not like his looks. He had a sallow, malarial complexion, shifty eyes and loose-knit, gangling build. There was a hard, cunning look about his mouth, and he wore a large revolver very conspicuously on his belt. Scott had the feeling that he was being very narrowly watched, but whenever he looked at Mr. Roberts he found him deeply absorbed in something else. They finished their salt pork, hominy and grease-soaked beet greens in comparative silence.

“Reckon maybe you’d like to see the still if you are new to these parts,” Mr. Roberts remarked to Scott.

“Yes,” Mr. Graham answered for him, “we both want to see it. I never get tired of hearing that old still growl.”

They walked down the street a little way to the still. It was not a very imposing-looking building. A roof set on posts over a copper still which was built into a brick firebox. There was a platform at the side on which the crude resin was unloaded from the wagons and dumped into the retort and a shed on the other side where the turpentine was stored. Sitting on the ground and a little apart from the shed was a small army of rough barrels full to the top with solid resin.

Mr. Graham explained the process to Scott. “You see they dump the resin just as they bring it in from the woods into that retort and heat it. The turpentine is boiled out and goes out of that little pipe at the top in the form of gas. Then they run the pipe down through some cold water and the gas condenses into liquid turpentine which they put into those tight barrels. When it makes just the right noise they pour some water into the retort to help the process along. Is she pretty near ready to growl, George?” he called to an old darky who was tending the retort.

“Ought to be pretty nigh, boss,” the old man grinned. It was evidently a familiar question for which he was listening and it tickled him.

“When all the turpentine has gone off they pour the resin into those rough barrels,” Mr. Graham continued. “It hardens so quickly that the barrels do not have to be very tight. They put them together right here.”

“Is that all they have to do to get the kind of turpentine that is used in paint?” Scott asked.

“Oh, some of it is redistilled and refined a little for certain uses but much of it is used just so.”

They walked around the place a little and Scott learned many interesting facts about the turpentine industry. There was a lot more he wanted to know but the old darky called them excitedly. “She’s startin’ to howl, boss.”

They hurried over to the still and could hear a peculiar growling sound coming from the retort. “That’s the stuff,” Mr. Graham chuckled. “Now listen to her when the water goes in.”

The water was poured in and the roar was up to expectations. “That makes her talk,” Mr. Graham laughed. “Now we might as well be going. She won’t growl again for a long time.”

“Dat’s right,” the old darky chuckled. “Won’t be nuffin’ mo’ fo’ yo’ to heah for some time.” He fully appreciated Mr. Graham’s joke of hearing the old still growl.

Mr. Roberts walked back to the house with them to get their horses. “See anything suspicious at the pond this morning, Mr. Burton?” he asked casually.

“Oh, no, nothing except Murphy,” he added with a laugh. He said it as carelessly as he could, but he watched Roberts keenly. He felt somehow that this sallow cracker was surely connected with the pond mystery and he wanted to see if the mention of Murphy’s name as a suspicious character would affect him. If it did, he did not show it. He seemed to have asked the question simply to make conversation and only grinned at Scott’s answer.

As they were mounting Mr. Roberts pulled his revolver and carelessly shot a toad which was hopping across the road some fifteen yards away. “Getting near pay day,” he said in explanation, “and I have to get in practice.”

Possibly it was nothing more than the natural temptation for a man with a gun to shoot any live thing he sees, but Scott, with his intuitive dislike of the man, felt sure that it was meant for a warning display of his skill with a gun and he thought about it in silence on the ride home through the whispering pines.

The next morning Scott started out early. He went alone, explaining to Mr. Graham that he wanted to scout the big swamp and see if he could find any clues. He did not know what they would be but he felt that it would be impossible to hide anything out in the open pine country, and that the key to the mystery must be somewhere in that gloomy swamp. He had studied the map thoroughly the evening before and had made an outline tracing of the swamp to carry with him. Armed with this map and a consuming curiosity he set out on foot for a point on the river where Mr. Graham assured him he would find a small bateau.

It was a bright, sunshiny morning when he started, but even before he reached the river the wind changed to the south and a dense fog rolled in off the gulf. In fifteen minutes the water was dripping from the trees as though from a heavy rain. The effect was almost weird. The trunks of the trees immediately around him were plain enough; at fifty feet they looked like ghosts. He walked in that little circle of forest and felt like a man in a cage. New trees loomed out of the fog ahead, stood boldly out as he passed them, and were quickly swallowed in the shroud behind. The trunks seemed to run up into the very sky and the tops were lost to view. It was Scott’s first experience with a real fog and he realized how easy it would be to get lost.

By keeping a careful watch he finally succeeded in locating the trail to the river and had no difficulty in finding the bateau just where Mr. Graham had told him it would be. It was a peculiar-looking craft twelve feet long and two and a half feet wide in the middle. It was even narrower at the ends which were square like a barge. It was flat-bottomed and fully deserved the description of “tippy” which Mr. Graham had given it. There was a rough, home-made paddle beside it. Scott was used to handling a canoe, but he found this new boat far crankier than anything he had ever seen before. It seemed to lurch sideways without the slightest provocation. In the first mile up the river he came within an ace of upsetting a dozen times. Gradually he learned the balance of it and got along pretty well. It did not seem to draw any water at all. Mr. Graham had said that it would float free on a light dew.

Toward the middle of the morning the fog burned off and the skies were clear once more. The shores were low and fringed with heavy brush, back of which was a strip of mixed hardwood forest made up mostly of hickories, oaks, and gums. It reminded Scott of the tropical stage settings he had seen at the theater. Now and then a little green heron or a big hooper crane would flop silently off an overhanging limb and disappear lazily around a bend in the river. Once he thought he saw the eyes of an alligator sticking out of the sluggish water, but they sank silently before he could make sure. Gray squirrels were scampering all through these hardwood trees, but they, too, seemed to be utterly silent. Scott felt like one of those old Spanish explorers who had made their way through that same country almost five hundred years before. It did not seem as though things could have changed much since then.

Three miles up the river the east bank melted away and the big swamp began. This was the place which Scott had come to explore. He turned the bateau and paddled out of the river into the swamp. The break in the bank was only a narrow one and beyond the passage the strip of hardwoods continued as before, but it was a very narrow strip and back of it as far as the eye could see the swamp ran parallel to the river. The timber was almost as heavy here as it was on the dry land, but they were the great gaunt cypress trees instead of the hardwoods. The cypress is the largest tree east of the Pacific coast forests, and there in the gloom of the swamp decked out in the great festoons of Spanish moss, they seemed giants indeed. Around each one were a number of cypress knees, peculiar, stake-like growths which come up to the surface of the water to get air for the roots. Some stuck up high out of the water, others did not quite reach the surface. These last had a disconcerting way of poking into the bottom of the boat or interfering with the paddle. Several times they almost capsized the cranky little bateau. “Ought to have a pilot for these reefs,” Scott growled, as he threaded his way slowly through them.

He decided to skirt the east shore first and see how large the thing really was. It might take days, even weeks to see it all, but he felt sure that the solution of the mystery was here in this swamp and he did not know any other way to get at it. The swamp seemed even more silent than the river. Scott found it even more fascinating. Occasionally enormous turtles poked heads almost as large as saucers, and about as flat, above the surface and eyed him curiously. He saw several black, hairy spiders with a three-inch spread of legs crawling on the tree trunks, and twice he saw fat, cotton-mouthed moccasins uncoil themselves sluggishly from the trunks of fallen trees and glide silently into the water.

Mile after mile he wound his way slowly among the trees and the cypress knees, always keeping in touch with the ragged shore line, and watching keenly for any sign of a trail or landing place. He found many of them but they all turned out to be animal trails which showed no trace of a human footstep. They were, nevertheless, intensely interesting to Scott. He had always prided himself on his woodcraft, and these medleys of coon, fox, wildcat and deer tracks were offering him new fields to conquer. He became so interested in them that he traveled on and on from one trail to another, wholly forgetful of time. He found dozens of smaller tracks in the black, plastic mud, tracks which he did not know, and it piqued both his pride and his curiosity. He almost forgot his object in coming there.

He had pottered along this way for several miles, following the crooked shore line of the swamp and stopping to examine every trail when a sudden pang of hunger caused him to glance at his watch. It was three o’clock. He laid his paddle across the bateau in front of him and sat there idly watching the shore while he ate his lunch. He had not thought to bring any water and the black waters of the swamp looked uninviting. However, he was well accustomed to eating dry lunches in the Southwest and made out very well. He decided that he would continue his search till four o’clock and then start for home; but he became so interested that he overstayed his time a little. It was half-past four before he realized it.

Scott knew that he could never reach the landing, probably not even find the passage out of the swamp, before dark, if he retraced his course around the jagged shore line. It would be much shorter and quicker to go directly across the swamp to the hardwood bottom and then follow that down to the opening. Unfortunately, the sun disappeared behind a bunch of leaden clouds before he had gone very far and left him without a guide. The sameness of the swamp and the utter lack of landmarks made it hard to hold the course, but he felt pretty sure of his directions and paddled on confidently as fast as the cypress knees and partially submerged roots would let him. Fallen trees and clumps of brush forced him to make many short detours which were very confusing. He had come much farther that morning than he had realized.

He had not seen any trace of the hardwoods along the river when darkness came with the swiftness so characteristic of the southern nightfall. Darkness seemed literally to fall on him. There was not a star in the sky and it was impossible to penetrate the black veil for even a few feet. He almost bumped into the trees before he could make them out, and the cypress knees which he could not see at all seemed to be everywhere. And yet he groped his way along in the hope of reaching the river.

About nine o’clock the skies cleared. The light helped him to make a little faster progress, but he could not see any stars that he knew, and could not make sure of his direction. He had almost come to the conclusion that there was no limit to this swamp, when a bank of black shadow loomed ahead of him. It was a shore line of some kind. Through the screen of brush he caught the shape of a pine tree outlined against the sky. It was not the hardwood strip along the river.

There was no use in going any farther now. He was about as completely lost as he could very well be. The moon would be up about eleven and he might as well wait for it right there. He sat motionless in the boat and listened to the small noises of the night, an occasional splashing along the edge of the swamp, the cry of a night heron, or the rustling of restless, small birds in the branches overhead. A gentle breeze was blowing from the direction of the forest.

Once a faint crackling in the brush, the faintest snapping of a tiny twig sounded loud there on the water, told him something was coming toward him. His eyes had become pretty well accustomed to the uncertain light, and as he watched he recognized the form of a large raccoon making his way out on to a log which extended quite a way into the water. It was not over twenty feet from the boat. Wholly unconscious of the silent observer the coon deliberately began to prepare his evening meal which he had evidently brought with him. He tore it into pieces, just what it was Scott could not see, and carefully dipped a piece in the water. Then he solemnly proceeded to wash it. He rubbed it between his front paws and scrubbed it as thoroughly as any laundress, and in much the same way. When he was finally satisfied of its cleanliness he repeated the process with another piece. His meal ended, he washed his hands and waddled ashore. Scott had often heard that the coon would eat nothing without first dipping it in water, but he had never imagined any such thorough scouring as this. He no longer regretted getting lost. Such a chance as that repaid him several times over.

He was almost sure once that he heard the creaking of a chain, but it was very faint and was not repeated. Shortly the moon came up almost directly in front of him. He was headed straight away from the river. With the shadows to guide him he turned to the west once more. A couple of hours’ paddling brought him to the hardwood bottom land and he soon found a passage through to the river. It was not the same passage where he had come in, but one considerably farther up the river.

From there on he had no trouble in finding his way. The tide was running out and the bateau traveled freely. He had marked the landing well and soon had the boat hidden in the accustomed place. When he sneaked quietly into the cabin it was half-past three, but he stopped to have a look at the pantry before he turned in.

Mr. Graham raised his head and had a squint at him, but he did not ask any questions, he did not have to—he knew what had happened to a man in a strange swamp on a cloudy day.

The next morning Scott went back up the river to continue the exploration of the swamp. He had some provisions along this time and was determined to stay out until he had finished the job. He would lose too much time going back to the cabin every night. He also had a compass. He decided to paddle on past the first channel into the swamp to the one where he had come out the night before, or rather early that same morning. It had appeared to him the night before to be about a half a mile farther up the stream. He had certainly covered much more than that distance now, but had not discovered any sign of it. Perhaps it had seemed shorter traveling downstream. He would go on a little farther. For another half mile he poked along the shore examining every break in the brush which might indicate a passage, but none of them proved to be any more than a little bay in the shore.

He knew now that he must have passed it. He considered paddling on up to the channel which the loggers used and starting his search from there, but he thought it might be better to keep his search a secret till he had completed it, and turned back to hunt once more for the hidden channel.

“Seems funny,” Scott muttered to himself, “that I could stumble through that passage in the night and can’t find it now in broad daylight.”

He paddled briskly back to the place where he had started his careful search. From there on he examined every foot of the shore. He had not gone very far when he stumbled on to a clump of tall brush which overhung the water. Ordinarily he would have passed it without a thought, but he was looking for something now, and he pushed the bushes aside with his paddle to make sure. There, sure enough, he looked into a perfectly clear and open channel through the bank into the swamp. It was broad on the inside like the top of a funnel and it was quite easy to see why it had not impressed him as a hidden channel on his outward trip. He wondered whether its existence was known to the loggers. He examined the shores and the approach, but could not find any trace. Of course that was no proof that boats had not used it, but it was hardly possible that any great number of logs had ever been worked through it without leaving some evidence.

He struck out boldly across the swamp, traveling due east, and soon came to the forest shore. A brief examination told him that he had passed there the day before and he paddled rapidly northward till he recognized the beginning of new territory. From there on he took up a minute examination of the shore line. After his experience with the passage into the river he was even more careful than he had been the day before. All day long he poked slowly in and out of the little bays, scrutinizing every trail and not forgetting an occasional glance out into the swamp. Not a single sign did he see to indicate that any one had ever been in the place before.

Night fell on him unexpectedly as on the night before and he determined to land and camp in the pine forest. He landed on a big log which extended out into the water and made the bateau fast. The night was so clear and warm that he decided not to put up a tent. His sleeping bag would give him all the protection that he needed. As he was still bent on keeping his whereabouts secret and did not know how near to the camp he might be, he determined to go without a fire and content himself with a cold supper. Ordinarily he would have picked a location next to a log or tree, but when he thought of the enormous spiders he had seen and the venomous scorpions of which he had heard, he selected an open spot in a little clearing. He could not put the rattlesnakes and cottonmouths entirely out of his mind, but he tried hard to forget them.

His simple supper was soon eaten and he sat in the starlight once more, listening to the small noises of the night. To the uninitiated these small noises often pass unnoticed and seem only to intensify the stillness. With many of them Scott was already familiar, but in this strange country there were others with which he was wholly unfamiliar. While he was trying to identify some of these he heard once more the creaking of a chain. It had been so faint the night before, and turtles and frogs are capable of such strange, creaking noises, that he had not been sure of it, but it was nearer to-night and he caught a distinct metallic ring in it.

Scott was all excitement now. He listened so intently that it almost hurt, but the sound did not come again. Once he thought that he heard the drip of a paddle but he could not be sure of that. It was possible that he was in sound of the camp. Sound travels far over the water on a still night. He had no idea where the camp was. But if he were close enough to the camp to hear the creaking of a chain he would certainly hear other noises unless the camp was very different from any other he had ever seen. It was a great temptation to scout around the edge of the swamp on foot in an attempt to locate the camp, but that would be foolish and possibly dangerous when he was so unfamiliar with the country. The pine had not been cut here as yet. That was a pretty good indication that he was not anywhere near the camp.

He sat long into the night, long after the moon had risen, listening, but in all that time not another suspicious sound came out of the weird tangle of the swamp. It was past midnight when he relaxed his straining nerves and crawled into his sleeping bag with a shiver, for he had not noticed the damp night chill which had crept into his very bones while he was sitting there motionless. Several times he caught himself listening again, wild-eyed, and even after he finally went to sleep he continued to dream of that creaking chain so vividly that in the morning he could not tell whether he had really heard it again or not.

So eager was he to investigate that curious sound that he could hardly wait to eat breakfast. All his stuff was soon loaded in the old bateau and he set off excitedly on his search. The question was, should he continue to follow the shore line as he had been doing or should he take the direction from which the sound had seemed to come? He decided to follow the shore line. It would be better to complete the shore line and then examine the open swamp. Scott always liked to know what was behind him. He soon found that he had not slept very close to the camp. The shore line was bare of trails here and he traveled at a lively pace. Yet, at the end of an hour, he had not seen anything of the pond or the logging camp.

“This blamed old swamp must connect with the Lake of the Woods,” Scott growled as he paddled on. “It does not seem as though we could have ridden this far the other day.”

When he rounded a point a half mile farther on, where an arm of the swamp ran off to the eastward, he suddenly saw the camp and the log pond before him. He sat motionless in the bateau and looked the place over in detail. It was much as it had been when he saw it before except that there were more logs in the pond. Only one man was in sight. He was working up at the other end of the pond building a section of a raft.

Scott watched this man thoughtfully for some time. He bored a hole through the end of a four-inch pole with a large augur and also bored another hole near the end of one of the logs. Then he drove a wooden peg through the hole in the pole and into the hole in the log. He repeated this operation at the other end of the pole with another log. Then he fastened the other ends of these two logs together in the same way. That made the framework for his raft. With a long pike pole he herded some other logs over to this frame. By pressing down on the pole he made the logs one by one duck under the crosspole and take their places between the two outer logs. When the space was filled this section of the raft was completed. He then proceeded to build another just like it. A number of these sections would be chained together end to end and the long, snakelike raft would be ready for its trip down the river.

“Where in thunder did you spend the night?”

The voice was so close to him and so unexpected that Scott almost upset the cranky little bateau. Then he recognized a face staring at him out of a clump of bushes close beside the boat and realized that he was near the stump where he had seen Murphy perched on their former trip.

“Hello,” Scott answered somewhat uncertainly when he had sufficiently recovered from his surprise. He was chagrined to think that he had not seen Murphy before. “Been there ever since we left?”

The man at the other end of the pond was too far off to hear their voices, but Murphy was afraid their conversation might reveal his hiding place. “Back up out of sight,” he said, “and I’ll join you.”

Scott retreated out of sight of the pond and Murphy soon joined him in a tiny bateau.

“No,” Murphy said in answer to Scott’s question, “I have not been there ever since you left, but I spent the night there. Where were you last night?” he repeated. He seemed to be excited.

“How do you know that I was not at home?” Scott asked suspiciously.

“You’d be some paddler if you got up here this time of morning,” Murphy laughed.

Scott had not thought of that. “I camped down there in the woods a couple of miles, near the edge of the swamp.”

“Did you hear the creaking of a chain about nine o’clock?” Murphy asked with suppressed excitement.

“I thought I did,” Scott replied cautiously.

“So did I,” Murphy exclaimed emphatically. “It was rather faint but it could not have been anything else. There was something doing out there in that swamp somewhere. I took a sneak out that way, but could not find anything.”

There was no doubting Murphy’s sincerity. He was fairly quivering with excitement. His knowledge of the country and his familiarity with the ways of the loggers would be of great help and Scott threw his suspicions to the winds. Moreover, he wanted somebody with whom he could talk. “I heard it the night before, too,” he confided.

“Did you?” Murphy exclaimed eagerly. “I was not here that night. What are you going to do now?”

Scott explained what he had already done and suggested that Murphy join him in completing the examination of the rest of the shore line. Murphy was more than willing.

“They seem to be getting a raft ready to send out now,” Scott said. “Do you know when they will start with it?”

“Usually start about the time the tide turns out. That will mean about five o’clock this afternoon.”

“Have you any grub?” Scott asked.

“No, but I can get some pretty quick. Ought to go to the cabin before I go off anywhere anyway.”

“All right. I’ll go up with you. Then we’ll make the rounds of the river bank and wait down there to see that raft go by.”

They landed well out of sight of the logging camp and struck off through the woods for Murphy’s ranger cabin.

Murphy had a very attractive little cabin back there in the woods and a little wife who looked perfectly capable of running things while he was away, and while he was home, too, if necessary. She did not seem in the least alarmed at the prospect of being alone for possibly two or three days. Murphy tossed the necessary supplies into his pack sack and they were soon on their way back to the bateau. They loaded all the duffle into Scott’s boat and Murphy took the bow paddle.

It seemed that the log pond was a natural, bottle-shaped arm of the big swamp. From the mouth of it to the river a quarter of a mile away a channel had been cleared of all brush and cypress knees which might interfere with the passage of the log rafts, but there were no booms or anything else to separate it from the rest of the swamp.

“They pole the rafts out that channel to the river,” Murphy explained, “and let them drift with the tide and the current the rest of the way.”

“I should think they would be hung up on the banks all the time,” Scott objected.

“Oh, they don’t turn them loose. There are always two men on them. There is a long sweep on each end of the raft, and by means of those they can usually keep in the channel and make the bends all right. Of course they have to tie up when the tide comes in and wait till she turns again. It is an ideal lazy man’s job, and these niggers love it.”

The north shore of the swamp swung considerably farther to the north and they were at least two miles above the channel when they came out on the river. In all that distance they had seen nothing but animal trails similar to the ones which Scott had found lower down. Murphy was able to explain many of the tracks which had puzzled him.

The hardwood strip was wider here and they landed to explore it. It was a quarter of a mile across to the river, but a coon trail was the only sign of life which they discovered.

“Well,” Scott said, “it may not help us any but we have the satisfaction of knowing that nothing goes into or comes out of that swamp except at the logging camp or by way of the river.” He had not been looking for anything in particular and did not know exactly whether he felt disappointed or relieved at not finding it. They knew now where they did not have to look for the thieves and that would help.

They returned to the boat and continued to examine the shore down to the log channel. The strip of dry land was only about four rods wide at this point. The channel was not a natural opening like the two which Scott had found below. It had been dug out and showed very clearly the signs of much use. The banks had been gouged out by the passing rafts, and tramped by many feet. They searched the ground for some distance on either side but could not find anything to show that the men who had made the tracks had ever done more than step ashore to help shove the rafts through the channel.

It was getting rather late in the afternoon but they thought they would have time to paddle downstream to see how many openings there were into the river and get back in time to see the raft come out. As the tide was coming in they stayed in the swamp. It is very often some little thing like this which changes the whole course of events. If they had only gone down the river. But they did not.

They did not examine the shore here with the same care. It did not occur to them that there could be anything there of particular interest. About a mile brought them to the first one. It was much broader and deeper than the one Scott had found in the morning, but was so overhung with trees and brush that it would not be readily noticed from the river. A rather hurried examination did not reveal any traces of use. They did not know how much farther down they would have to go and were anxious to get back before the raft went out. Another mile brought them to another opening.

“That settles that part of it!” Scott exclaimed. “This is where I went in this morning. There is only one more opening below this, and that is down at the lower end of the swamp. I have been all the way around her now. There are just these four channels into the river.”

“And two of them,” Murphy said, “are new ones on me. I have been down that river dozens of times. Funny I never noticed them.”

“They are pretty well screened from the river,” Scott replied. “Don’t look as though either of them had ever been used.”

Without further search they paddled back for the log channel so that they would not be in the way of the raftsmen, and had just time enough to pick a good hiding place before it was dark. The sky was clear and from where they sat they could see the river and the mouth of the log canal plainly. A fire was out of the question and they ate their cold supper in silence.

Scott was getting used to this night gloom in the big swamp now. It did not seem as weird as it had before, possibly because he was not alone, but there was a certain fascination about it which kept his interest on edge. The monotonous splashing of the drooping branches dipping in the current seemed to take on a certain musical rhythm. The booming of the bull bats as they dropped down into the opening over the river and the honking of the lonely night heron fitted in like the solo parts in an orchestra. Suddenly there was a shriek which made Scott’s blood run cold. It certainly could not have been written in the music.

“What in thunder was that?” he whispered excitedly, and then joined in the silent laugh with Murphy. Even before he had finished speaking he had recognized the hunting cry of the great barred owl. There is no more blood-curdling sound, and coming as it did on tensely listening nerves it had raised the hair on both their heads.

“That is enough to make every mouse and small bird in the woods die of heart failure,” Scott whispered.

“Probably what he does it for,” Murphy whispered back. “A little more and he’d got me, too.”

It was not till about eleven o’clock that they heard the sound of voices floating faintly toward them from the direction of the pond. After a long silence they heard them again much nearer, and soon the splash of the poles trailing through the water was distinctly audible. The blow of a hammer and the clank of a chain caused Scott to look at Murphy inquiringly.

“They have to break up the raft to get it out into the current,” Murphy whispered.

After considerable delay and splashing three sections of the raft shot out of the canal and swung downstream as they were caught by the current. They were tied to a tree by a rope and swung back against the near shore. After another delay and more splashing another three sections appeared and settled neatly in behind the others. Two men came quickly out of the shadow on to the raft and chained the two parts securely together. They disappeared to untie the mooring ropes, appeared again quickly to man the sweeps and slowly worked the raft out into midstream as it glided down the silent current. It seemed like a ghost raft on the river Styx.

The two men in the brush watched intently as the raft glided by. No sooner were they out of hearing than Murphy turned excitedly. “Those were white men on that raft,” he whispered. “The light was too uncertain to make them out, but they were white men and one of them looked like Qualley.”

“The fellow in the bow looked to me something like that superintendent at the turpentine camp,” Scott said doubtfully, “but I may have been mistaken. I have never seen him but once.”

“Yes, sir, that’s exactly who it was. Now what do you suppose he is doing over here?”

Before Scott could answer they both heard quite distinctly that clanking of a chain which had come to them the night before from somewhere out there in the swamp. It was much plainer than it had been before and seemed nearer. They listened intently for a few minutes but heard nothing more.

“Let’s take a sneak out that way,” Murphy suggested eagerly.

Scott nodded and they scrambled silently across the neck of land to the boat in the swamp. “Don’t make any noise,” Scott cautioned. “We do not want them to know that we are on the lookout any sooner than we can help.”

The moon had not yet come up and it was so dark back there in the swamp that they made slow progress. Every few minutes they stopped to listen. Once or twice they thought they heard a faint splashing, but sounds are very hard to locate in such a place. After more than an hour of fruitless search they gave it up.

“Now, what?” Murphy whispered as they sat disconsolate in the middle of the swamp.

“How far is it down to the place where they sell those logs?” Scott asked thoughtfully.

“About fifteen miles.”

“Will they make it with that raft to-night?”

“No, they tie up during the flood tide, you know, and they had already lost a couple of hours of the ebb when they started. They will not get more than half way.”

“Let’s follow them,” Scott suggested. “I don’t suppose we shall see anything, but I would like to talk to those people at the mill.”

Murphy agreed and they were soon threading their way through the cypress knees back to the log canal. They reached there just too late to see another bateau disappear up the channel toward the camp. They glided out into the river and paddled silently with the current. As they did not know where they might run on to the raft they approached all the bends cautiously.

“The tide will be turning pretty quick now,” Murphy whispered. “When it does they will tie up, and when they tie up they will go to sleep. That will give us a chance to get around them.”

Some distance farther down they were sneaking cautiously around a bend when Murphy held up his hand in warning and Scott brought the bateau to a stop. Not fifty yards away they could see the shadowy outline of the raft lying close in under the shadow of the trees. There was a small fire burning at the far end of it and they could see two forms flitting about in the flickering light. They had evidently just arrived and were busy making the raft fast to the shore.

The amateur detectives pushed their bateau well in under the shadow of the brush-covered bank and settled down to watch. They did not have long to wait. The men soon completed their preparations and settled down beside the fire. The low sound of voices soon gave place to silence which was in time broken by a long whistling snore.

“That is accommodating of that fellow,” Scott whispered. “If it were not for his music we might have sat here for an hour trying to find out whether he was asleep. Shall we make a sneak for it?”

“Better wait a few minutes,” Murphy suggested, “till we can make sure of the other fellow.”

The other man was either awake or he did not snore. They listened in vain for ten minutes and decided to take a chance on it.

“Think we better try to steal by under the shadow of the opposite shore?” Scott asked.

“Not for mine,” Murphy answered, “the fellow might be awake and mistake us for a deer. I’d rather take a chance on floating right down the middle of the stream.”

Scott thought the suggestion a good one. He had seen one of those men shoot and he did not feel like playing deer for him. The moon was just coming up and would make them uncomfortably conspicuous, but there was nothing else to do unless they wanted to wait there all night. A single shove sent the bateau out from the shore and it floated very slowly down the stream. The tide was just on the turn and it seemed that they would never get by that raft. At last they were out of sight around a bend in the river. They paddled silently for a few minutes. Then Scott’s excitement broke all bounds.

“Did you notice anything peculiar about that raft?” he whispered eagerly.

Murphy shook his head.

“There were eight sections in it.”

“No,” Murphy exclaimed incredulously.

“Yes, sir, I thought it was a mile long from the length of time it took us to get by and I counted the sections. There were eight.”

“Where in thunder did they pick up the other two?”

Neither of them had any answer for that and they paddled on, thoughtfully silent. It was possible that the raft had broken the night before and they were picking up the pieces. There was not much chance now of finding out where they got it. The next best thing would be to see how they got rid of it.

“What’s the matter with our getting some sleep?” Murphy asked. “We can go ashore till the tide turns. They can’t start before that and we can easily beat it out ahead of them.”

There did not seem to be any good reason why they should not and they turned in to the first high land they saw. They built a fire and made the coffee they could not have at supper. The night had turned cold enough for them to get pretty well chilled while they were watching the raftsmen go to sleep. The fire and the coffee soon warmed them up. They hauled their blankets out of the boat and were soon asleep beside the little fire.

Murphy had figured that the tide would turn again at about six o’clock in the morning. By five he was up getting breakfast. Scott soon joined him. There was a cold fog hanging over the river and they crowded close around the fire. The temperature was not conducive to conversation. It was not till the heat of the fire had thawed them out a little that Murphy broke the silence.

“Are you dead sure that there were eight sections in that raft?” he asked. It was the second time that Scott’s observation had proved better than his own and it piqued him a little. The power of observation is one of the woodman’s most valuable faculties.

“I sure am,” Scott replied, “I counted them twice.”

“Do you suppose those fellows are selling those logs to the mill on a separate account?”

“That is what I want to find out if I can. I thought it would be interesting to see how they handle the thing when they come in with the raft.”

Murphy chuckled. “It will be good sport to stand there and see them sell those logs which they have been to so much trouble to steal for the credit of the company.”

They were in high spirits and sent the bateau skimming down the river at a tremendous rate. It was not yet nine o’clock when they landed at the mill dock. They knew that the raft could not get in before ten or eleven. It was the first southern mill Scott had ever seen, with its great open pile of ever-burning sawdust and slabs blazing away as though to invite the destruction of the mill by fire. The upper part of the mill was built like a summer house, with open sides. Instead of the little short logs he had seen in the north the big band saw was ripping up logs forty and even sixty feet long.

The manager saw them and came over for a chat. He knew Murphy and greeted Scott cordially. “Still looking for the timber thieves?” he asked pleasantly.

“Still at it,” Murphy admitted.

“I suppose you get a great many logs in here from all up and down the river?” Scott asked.

“No,” the manager answered, “not now. We used to buy in small lots from many owners, but that was before Qualley started up there. We had quite a supply on hand when he started and he is getting the stuff down to us now just about fast enough to keep us going. We only cut about forty thousand feet a day. I am not sure, but I do not believe that we have bought a log from any one else for almost a year.”

“Are there any other mills on the river?” Scott asked.

“No, this is the only one down this way. There may be some more up the river, but if there are they are a long way up.”

Just then a big doubledeck river steamer with her tall smokestacks and queer-looking stern paddle wheel went by spanking her way up against the current.

“Don’t suppose one of those things would tow a raft up the river?” Scott suggested.

“Too slow for them. They are slow enough any way and a raft tow would cost her more than the logs are worth.”

“I don’t see what good it would do any one to steal logs here, then,” Scott said. “What could they do with them when they get them?”

“That’s what Murphy has been trying to find out for a couple of years,” the manager laughed. “He thought for a while that I was buying stolen property here, but he has never been able to prove it on me. Like to look over the mill, Mr. Burton?”

Scott was glad of the opportunity to keep in touch with the manager till the rafts came in, and eagerly accepted the invitation. They followed the manager through the strange mill which looked so much like a summer house to Scott with its open sides and elevated tramways leading out to the lumber yard. He watched the long logs come dripping up the jack chain on to the log deck, saw the powerful steam nigger toss the great trunks on to the long saw carriage as though they had been so many toothpicks and listened to the shriek of the big band saw as it tore through the screaming log. The explosive exhaust of the shotgun feed as the newly sawed plank fell away from the cant had always sounded to Scott like a shout of triumph. In five minutes that shining ribbon of steel had slashed up the growth of three or four centuries. Perhaps La Salle had marched beneath the branches of that very tree.

It was fascinating to watch the perfect working of those powerful machines, and Scott never tired of it, but he was watching to-day with only one eye, the other was on the bend of the river above the mill. They followed the lumber clear through the sorting shed and even out to the piles in the lumber yard; they examined the dry kiln and watched the noisy flooring machines in the planing mill, and even then the raft had not arrived. Scott glanced questioningly at Murphy. What could be delaying them so long?

It was almost noon before the nose of the tardy raft poked around the distant bend in the river. They were sitting in the office talking as usual of the mystery of the stolen logs. Scott was so glad to see the rafts that he felt like shouting, but he wanted to see what the manager would do. Possibly it would be a little embarrassing for him to have visitors from the National Forest at his elbow when the raft came in. But if Scott expected any such thing he was disappointed.