The Project Gutenberg EBook of Hogarth's Works: Volume 3 (of 3), by

John Ireland and John Nichols

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Hogarth's Works: Volume 3 (of 3)

With life and anecdotal descriptions of his pictures

Author: John Ireland

John Nichols

Release Date: May 29, 2016 [EBook #52181]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HOGARTH'S WORKS: VOLUME 3 (OF 3) ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

Footnotes have been moved to the end of the book text. Some Footnotes are very long.

One occurrence of the 3-star asterism symbol is denoted by ⁂. On some handheld devices it may display as a space.

The first two volumes of this work can be found in Project Gutenberg at

www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/51821 and

www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/51978

There are several linked references to specific sections of those books from this volume.

The cover was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

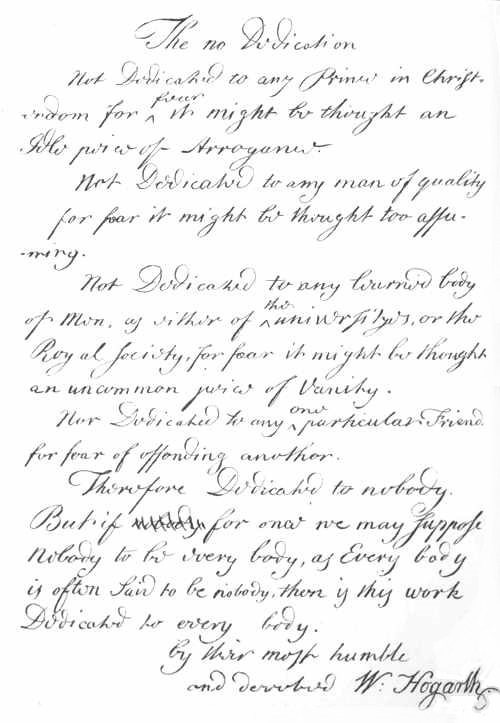

The no Dedication

Not Dedicated to any Prince in Christendom

for fear it might be thought an

Idle piece of Arrogance.

Not Dedicated to any man of quality

for fear it might be thought too assuming.

Not Dedicated to any learned body

of Man, as either of the universityes, or the

Royal Society, for fear it might be thought

an uncommon piece of Vanity.

Nor Dedicated to any one particular Friend

for fear of offending another.

Therefore Dedicated to nobody.

But if for once we may suppose

Nobody to be every body, as Every body

is often said to be nobody, then is this work

Dedicated to every body.

by their most humble

and devoted W: Hogarth.

HOGARTH'S WORKS:

WITH

LIFE AND ANECDOTAL DESCRIPTIONS OF HIS PICTURES.

BY

JOHN IRELAND and JOHN NICHOLS, F.S.A.

THE WHOLE OF THE PLATES REDUCED IN EXACT

FAC-SIMILE OF THE ORIGINALS.

Third Series.

London:

CHATTO AND WINDUS, PUBLISHERS.

(SUCCESSORS TO JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN.)

DESCRIBED IN THE THIRD SERIES.

| PAGE | |

| Fac-simile Autograph—"The No Dedication," | Frontispiece to |

| face Title. | |

| Dolphin Candlestick, | Title Page. |

| Do.(described), | 123 |

| Kent's Altar-Piece, | 24 |

| The Rape of the Lock, | 26 |

| Arms of the Duchess of Kendal, | 28 |

| Frontispiece to Artists' Catalogue, | 78 |

| Tail-Piece to Do., | 78 |

| The Vase, | 114 |

| Do.(described), | 112 |

| Hints for a New Capital, | 114 |

| Round and Square Heads, | 114 |

| Do.(described), | 116 |

| Hercules, Henry viii., and a French Dancing-Master, | 114 |

| Do.(described), | 119 |

| Charles i., Henrietta Maria, Italian Jupiter, etc., | 124 |

| [vi] The Dance, | 124 |

| Frontispiece to the Perspective of Architecture, | 132 |

| Taste in High Life, | 180 |

| Farinelli, Cuzzoni, and Senesino, | 184 |

| A Woman swearing her Child to a grave Citizen, | 188 |

| The Foundlings, | 192 |

| Captain Thomas Coram, | 192 |

| Frontispiece to Terræ Filius, | 194 |

| The Sepulchre, | 194 |

| The Politician, | 198 |

| The Matchmaker, | 200 |

| The Man of Taste, | 202 |

| Henry Fielding, | 206 |

| Simon Lord Lovat, | 210 |

| Nine Plates for Don Quixote: | |

| Plate I. The First Sally in Quest of Adventure, | 220 |

| Plate II. The Innkeeper, | 220 |

| Plate III. The Funeral of Chrysostom, | 222 |

| Plate IV. The Innkeeper's Wife and Daughter administering Chirurgical Assistance to the poor Knight of La Mancha, | 222 |

| Plate V. Don Quixote seizes the Barber's Basin for Mambrino's Helmet, | 224 |

| Plate VI. Don Quixote releases the Galley Slaves, | 224 |

| Plate VII. First Interview of Don Quixote with the Knight of the Rock, | 226 |

| Plate VIII. The Curate and Barber disguising themselves to convey Don Quixote home, | 226 |

| Plate IX. Sancho's Feast, | 228 |

| [vii] Heidegger in a Rage, | 230 |

| Large Masquerade Ticket, | 230 |

| The South Sea Bubble, | 238 |

| The Lottery, | 238 |

| Masquerades and Operas—Burlington Gate, | 238 |

| Beggars' Opera Burlesqued, | 242 |

| Twelve Plates of Butler's Hudibras, | 242 |

| Just View of the British Stage, | 246 |

| Examination of Bambridge, | 246 |

| Henry viii. and Anna Bulleyn, | 248 |

| Crowns, Mitres, Maces, etc., | 246 |

| Do.(described), | 249 |

| The Royal Masquerade, | 252 |

| Rich's Triumphant Entry, | 254 |

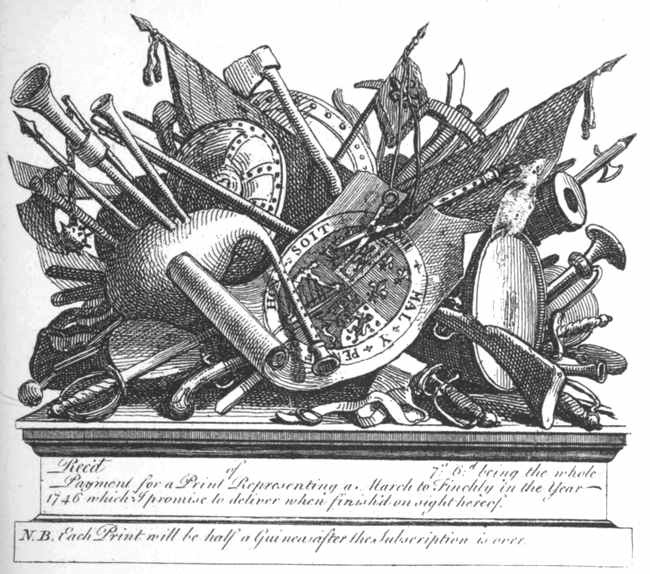

| Mr. Ranby's House at Chiswick, | 254 |

| Do.(described), | 262 |

| Hymen and Cupid, | 254 |

| Do.(described), | 263 |

| The Pool of Bethesda, | 256 |

| The Good Samaritan, | 256 |

| Martin Folkes, Esq., | 260 |

| Bishop Hoadley, | 262 |

| False Perspective, | 264 |

| Inhabitants of the Moon, | 264 |

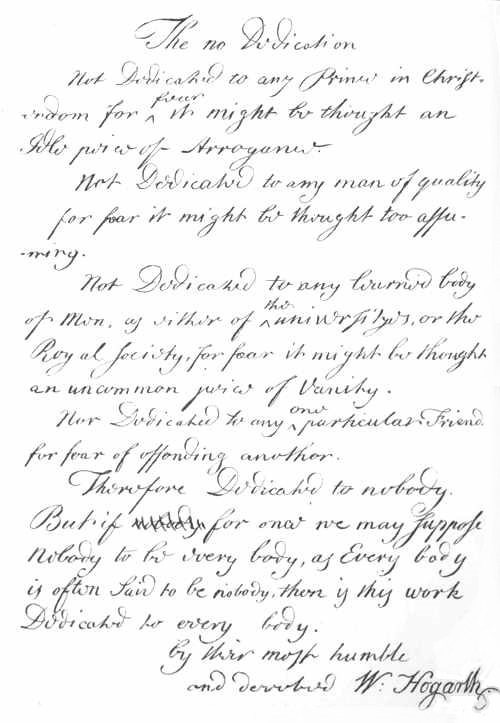

| Receipt for Print of March to Finchley, | 264 |

| The Farmer's Return, | 266 |

| [viii] Gravity, | 266 |

| Frontispieces to Tristram Shandy, | 266 |

| Four Heads from the Cartoons, | 268 |

| The Shrimp-Girl, | 268 |

| Lord Holland, | 268 |

| Earl of Charlemont, | 268 |

| The House of Commons, | 270 |

| Debates on Palmistry, | 270 |

| The Staymaker, | 270 |

| Charity in the Cellar, | 270 |

| Six Tickets, | 272 |

The manuscripts from which the principal parts of this volume are compiled were written by the late Mr. Hogarth; had he lived a little longer, he would have methodized and published them.[1] On his decease, they devolved to his widow, who kept them sacred and entire[2] until her death, when they became the property of her relation and executrix, Mrs. Lewis, of Chiswick, by whose kindness and friendship they are now in my possession.

This is the fair and honest pedigree of the Papers, which may be thus divided:—

I. Hogarth's life, comprehending his course of study, correspondence, political quarrels, etc.

II. A manuscript volume, containing the autographs of the subscribers to his "Elections," and intended print of "Sigismunda;" and letters to and from Lord Grosvenor relative to that picture.

III. The manuscript of the Analysis of Beauty, corrected by the author, with the original sketches, and many remarks omitted in the printed copy.

IV. A supplement to the Analysis, never published; comprising a succinct history of the arts in his own time, his account of the institution of the Royal Academy, etc.

V. Sundry memoranda relative to the subject of his satire in several of his prints.

These manuscripts being written in a careless hand, generally on loose pieces of paper, and not paged, my first endeavour was to find the connection, separate the subjects, and place each in its proper class. This, in such a mass of papers, I found no very easy task; especially as the author, when dissatisfied with his first expression, has frequently varied the form of the same sentence two or three times: in such instances I have selected that which I thought best constructed. Every paper has been attentively examined, and is to the best of my judgment arranged as the author intended. I have incorporated Hogarth's account of the Arts, Academy, etc., with his narrative of his own life; and to keep distinct the various subjects on which he treats,[xi] divided the whole into chapters. Where from negligence or haste he has omitted a word, I have supplied it with that which the context leads me to believe he would have used. Where the sentences have been very long, I have occasionally broken them into shorter paragraphs, and sometimes tried to render the style more perspicuous, by the retrenchment of redundant expressions; but in every case the sense of the author is faithfully adhered to.

As he has usually given the progress of his life, opinions, etc. in the first person, I have adopted the same rule; and to distinguish my own remarks from Hogarth's narrative, the beginning of each sentence written by him is marked with inverted commas. His correspondence is regulated by the dates of the letters; and the copies from sketches in the MS. Analysis are placed in the chapter which contains Hogarth's account of that publication.

In the papers which relate to the subject of his satire in some of his prints, he appears to have projected more than his life allowed him to perform; the few remarks which he made are inserted in the Appendix.

Prints are in general designed to illustrate books, but the Editor's part of this volume is written to illustrate Prints. He is apprehensive that the whole will stand in need of much indulgence, but certain that the errors, whatever they may be, do not[xii] originate in a want of diligence. To his thanks for the flattering reception of the first Edition, and rapid sale of the first and second Editions of the two preceding volumes, he has only to add his reasons for bringing forward this third. When they were published, he had neither seen the MSS., nor ever heard that Hogarth had written anything for the press, except the Analysis of Beauty. When he some time after obtained the papers, he considered them as a very valuable acquisition, and was vain enough to think that by arranging them he could compile a volume which would gratify the admirers of Hogarth; and in the hope that the life, opinions, criticisms, and correspondence of this great and original genius will excite and gratify curiosity, he respectfully submits the following pages to the candour and indulgence of the public.

J. I.

Mr. Walpole (in p. 160 of his Anecdotes) gravely declares that Hogarth had but slender merit as a painter, and in colouring proved no greater a master. By the six pictures of "Marriage à la Mode," both these declarations are answered and refuted.

Mr. Nichols (in p. 449 of his Anecdotes), at the same time that he kindly acknowledges "Hogarth's hand was faithful to character," roundly asserts that as an engraver his merits are inconsiderable; that he wants clearness; that his strokes sometimes look as if fortuitously disposed, and sometimes thwart each other in almost every possible direction. He adds, "that what the artist wanted in skill, he strove to make up in labour; but the result of it was a universal haze and indistinctness, that, by excluding force and transparency, rendered several of his larger plates less captivating than they would have been had he entrusted the sole execution of them to either[2] Ravenet or Sullivan." This is very severe; but is it true? If the "Harlot's" and "Rake's Progress," the "Enraged Musician," "Strolling Actresses," "Medley," and many other prints produced by his own graver, are attentively examined, I think the strokes will not be found to be fortuitously disposed: every touch tells, and gives that expression which the artist intended. As to his striving to make up for his want of skill by labour, I believe him to have been a prodigy of industry, but do not discover the result that is suggested by Mr. Nichols. We may possibly annex different ideas to the words. Johnson describes a universal haze as a fog, a mist; and indistinctness he defines to be confusion, uncertainty, obscurity,—faults which were never attributed to William Hogarth. Neither have I before heard it said that his prints want force: energy is in general their leading characteristic. As to transparency, if Mr. Nichols means that they have not that gauzy, glittering tone which marks many of our modern productions, I humbly conceive the artist did not desire such distinction; neither did he wish his works to be classed with such pretty performances: he was superior to the tricks of art, rejected all unnecessary flourish, and aimed at convincing the mind rather than dazzling the eye.

The two most difficult things in painting are character and drawing; and they are least under[3]stood by the crowd, who are invariably attracted by colour and glare. But for my own part, so far am I from thinking his style unsuitable to his subject, that I cannot conceive any manner in which his prints could be engraved that would be equal to his own. I prefer it to the most laboured copies of those miniature masters who, by fine finishing, fritter away all force.

Thus much may suffice for Mr. Nichols, from whom I am sorry to differ, as I owe him thanks for much useful information; but with the next critic upon the list it is dangerous to disagree.

For the talents of Mr. James Barry, Professor of Painting to the Royal Academy, I have the highest respect; his pictures in the Adelphi are an honour to the artist, and to the nation. In the sixth, representing the state of final retribution, he gives Hogarth a seat in Elysium; but in p. 162 of his description of the picture, etc. (published for Cadell), he has drawn this great artist in so motley a garb as leaves the reader in some doubt whether censure or praise predominates, and confers on poor Hogarth a sort of degrading immortality.

The Professor begins by admitting that "Hogarth's merit entitles him to an honourable place amongst the artists in Elysium, and that his little compositions 'tell' their own story with more facility than is often found in the elevated and more noble inven[4]tions of Raphael;" yet adds, "it must be honestly confessed that in what is called knowledge of the figure, foreigners have justly observed Hogarth is often so raw and unformed as hardly to deserve the name of an artist." Though he is often thus raw and unformed, yet Mr. Barry acknowledges that "this capital defect is not often perceivable, as examples of the naked and of elevated nature but rarely occur in his subjects, which are for the most part filled with characters that in their nature tend to deformity." Sometimes, I admit; but surely not for the most part. "Besides, his figures are small, and the junctures and other difficulties of drawing that might occur in their limbs are artfully concealed with their clothes, rags, etc." Mr. Barry surely does not mean that Hogarth needed any artifice to conceal an ignorance of anatomy, because Mr. Barry knows that many of his works prove a perfect knowledge of the figure. The Professor thus continues:—

"What would atone for all his defects, even if they were twice told, is his admirable fund of invention, ever inexhaustible in its resources; and his satire, which is always sharp and pertinent, and often highly moral, was (except in a few instances, where he weakly and meanly suffered his integrity to give way to his envy) seldom or never employed in a dishonest or unmanly way." A few instances! I do not believe it possible to point out one. Seldom or[5] never! Why is the Professor so parsimonious in his praise? He might safely have said never. It has been the fashion to call Hogarth an envious man; I cannot conjecture why. The critic surely does not mean to insinuate that there was any violation of integrity in Hogarth's retaliating the pictured shapes upon Wilkes and Churchill, or that he envied the character of the late worthy Chamberlain of the city of London!

Mr. Barry goes on: "Few have attempted to rival him in his moral walk. The line of art pursued by my very ingenious predecessor and brother Academician, Mr. Penny, is quite distinct from that of Hogarth, and is of a much more delicate and superior relish; he attempts the heart, and reaches it, whilst Hogarth's general aim is only to shake the sides." Whoever will turn over a portfolio of Hogarth's prints, will find that his satire had sometimes a higher aim. "In other respects no comparison can be thought of,"—in good truth, it cannot,—"as Mr. Penny has all that knowledge of the figure and academical skill which the other wanted." Can Mr. Barry conceive it possible that posterity will think Mr. Penny's line of art of a superior relish to that of Hogarth! Mr. Penny's academical skill I do not contest; but to say that Hogarth wanted all that knowledge of the figure, etc., is rather too much. I know that imperfections may be pointed out in some[6] of his works, but they had their origin in carelessness rather than ignorance.

Mr. Barry concludes by remarking, that "perhaps it may be reasonably doubted whether the being much conversant with Hogarth's method of exposing meanness, deformity, and vice, in many of his works, is not rather a dangerous, or at least a worthless pursuit; which, if it does not find a false relish, and a love of, and search after, satire and buffoonery in the spectator, is at least not unlikely to give him one."

That the Professor of Painting, after acknowledging Hogarth's satire was highly moral, should be apprehensive that contemplating such of his works as expose meanness, deformity, and vice, is dangerous, I cannot comprehend!

Considering their genius, general good tendency, and boundless variety, it would have been more candid to have viewed them through the medium of his beauties, than thus have distorted his faults, and reluctantly admitted his merits; but to such criticism his own works supply a short answer.

An instance of this occurred in 1762, when the author of the North Briton, among some other malign remarks, inserted the following paragraph:—"I have for some time observed Hogarth's setting sun: he has long been very dim, and almost shorn of his beams." A few weeks after the appearance of this candid critique, Hogarth published his "Medley," which,[7] considered in the first and second state, has more mind, and is marked with deeper satire, than all his other works!

By fastidious connoisseurs it has been said that his scenes are sometimes low and vulgar; but he carried into every subject the energy of genius, and marked every countenance with the emotions of the soul. He had powers more than equal to ascending into a higher region, though, as he might have lost in utility what he gained in dignity, this adherence to terrestrial objects is not much to be regretted. Had he wandered in heathen mythology, and chosen to people his canvas with demigods instead of the "Harlot's Progress," we might have had the "Loves of Venus and Adonis;" and in the place of the "Stages of Cruelty," the "Labours of Hercules."

To enumerate the little critics that stepped forth with the kind intention of unpluming this "eagle tow'ring in his pride of place," would be waste of ink; had they succeeded to their wish, not a feather would have been left in his wing. As an artist, he might have soared superior to their efforts; but when he commenced author, they found him within their reach, and renewed their attack with redoubled acrimony.

Mr. Wilkes, in the North Briton above quoted, calls him the supposed author of the Analysis. By some he was said to have borrowed a part of the work, and by others to have stolen the whole; nay, I have more[8] than once been seriously assured that every line was written by his friends. To this I can now reply in a style similar to that of the peripatetic, who, being told by a philosopher that there was no such thing as motion, gravely rose from his seat and walked across the room. I can produce the original manuscript, with the red chalk corrections by his own hand.[3] This supplement to that work, Hogarth wrote to vindicate himself from these and similar aspersions. In explaining his motives, he is led into stating his professional opinions; and in that part which relates to the Royal Academy, predicts that, on the plan they set out, the institution could never be of material use to the Arts. For one who is neither artist, associate, nor academician, to assert that Hogarth's prophecy is fulfilled, might be deemed too assuming. But, with little more claim to connoisseurship than I derive from a long and unreserved intimacy with some of the first painters of this country, I am led to fear that the wish their late President expressed in his first discourse is not likely to be speedily realized. He hopes that "the present age may vie in Arts with that of Leo the Tenth; and that 'the dignity of the dying Art' (to make use of an expression of Pliny) may be revived under the reign of George the Third."

This discourse was read in 1769; yet (let it not be told in Gath, nor whispered in the streets of Askelon), when in 1797 the students of the Royal Academy produced their drawings for the silver medal, not one of them was found worthy of the prize; and what (considering the recent discovery of the Venetian secret) was still more strange, all the pictures sent by the candidates for the prize of painting were rejected, and voted out of the room! This circumstance the Professor of Painting has recorded in his letter to the Dilettanti Society, and candidly admits that the fault does not lie with the students, but is in the Institution!

If it should be thought that Hogarth, in the course of his narration, seems too tremblingly alive, and sometimes offended where offence was not meant, let it be recollected that he must have felt superior to men whom the public preferred. To rank him with Kent, Jervas, Highmore, Hudson, Hayman, or any of that school of mannerists who figured in the different periods of his life, is classing a giant among pigmies. His works will bear the relative test of times when the Arts may be higher than they were then or are now; and I am fully conscious that this Memoir must derive its principal interest from the celebrity of the artist, who, like Louis de Camoëns, was a distinguished actor in the scenes he describes.

ANECDOTES OF AN ARTIST,

WHO HELD, AS 'TWERE, THE MIRROR UP TO NATURE.

CONTAINING MANY CIRCUMSTANCES RELATIVE TO HIS LIFE, AND OPINIONS OF THE ARTS, ARTISTS, ETC. OF THE TIMES IN WHICH HE LIVED; AND SUNDRY MEMORANDA RELATIVE TO HIS PRINTS.

Compiled from his Original Manuscripts, in the possession of

JOHN IRELAND.

HOGARTH'S OWN ACCOUNT OF HIS BIRTH AND EARLY EDUCATION. REASONS FOR HIS BEING APPRENTICED TO A SILVER-PLATE ENGRAVER; WITH WHICH EMPLOYMENT BECOMING DISGUSTED, HE COMMENCES AN ENGRAVER ON COPPER. METHOD OF STUDY. THE FATE OF THE FIRST PRINT HE PUBLISHED, ETC.

"As many sets of my works have been lately sent to foreign countries, and others sold to persons who, from their ignorance of the particular circumstances at which I aimed, have mistaken their meaning and tendency, I have been told that a short account of such parts as are obscure, or have been most liable to misconstruction, in those prints that are not noticed in Mr. Rouquet's book,[4] would be highly acceptable.

"I am further told, that the public have sometimes expressed a curiosity to know what were the motives by which the author was induced to make choice of subjects so different from those of other painters, and what were his modes of study in a walk which had not been trode by any other man. These reasons[14] will, I hope, be deemed a sufficient apology for my attempting the following brief history; in which must necessarily be introduced my opinion of the present state of the arts, and conduct of contemporary artists, and a vindication of myself and my productions from the aspersions which they have so liberally bestowed upon each.

"With respect to my life,—to begin sufficiently early,—I was born in the city of London, on the 10th day of November 1697, and baptized the 28th of the same month. My father's pen, like that of many other authors, did not enable him to do more than put me in a way of shifting for myself. As I had naturally a good eye and a fondness for drawing, shows of all sorts gave me uncommon pleasure when an infant; and mimicry, common to all children, was remarkable in me. An early access to a neighbouring painter drew my attention from play, and I was at every possible opportunity employed in making drawings. I picked up an acquaintance of the same turn, and soon learnt to draw the alphabet with great correctness. My exercises when at school were more remarkable for the ornaments which adorned them, than for the exercise itself.[5] In the former I soon found that blockheads with better[15] memories could much surpass me, but for the latter I was particularly distinguished.

"Besides the natural turn I had for drawing rather than learning languages, I had before my eyes the precarious situation of men of classical education. I saw the difficulties under which my father laboured, and the many inconveniences he endured from his dependence being chiefly on his pen, and the cruel treatment he met with from booksellers and printers, particularly in the affair of a Latin Dictionary,[6] the compiling of which had been a work of some years. It was deposited in confidence in the hands of a certain printer; and during the time it was left, letters of approbation were received from the greatest scholars in England, Scotland, and Ireland. But these flattering testimonies from his acquaintance[16] (who, as appears from their letters which I have still by me, were of the first class) produced no profit to the author.[7] It was therefore very conformable to my own wishes that I was taken from school and served a long apprenticeship to a silver-plate engraver.

"I soon found this business in every respect too limited. The paintings of St. Paul's Cathedral and Greenwich Hospital,[8] which were at that time going on, ran in my head, and I determined that silver-plate engraving should be followed no longer than necessity obliged me to it. Engraving on copper was, at twenty years of age, my utmost ambition. To attain this it was necessary that I should learn to draw objects something like nature instead of the monsters of heraldry; and the common methods of study were much too tedious for one who loved his pleasure and came so late to it, for the time necessary to learn in the usual mode would leave me none to spare for the ordinary enjoyments of life. This led me to considering whether a shorter road than that usually travelled was not to be found. The early part of my life had been employed in a business rather detrimental than advantageous to those branches of the art which I wished to pursue, and [17]have since professed. I had learned by practice to copy with tolerable exactness in the usual way, but it occurred to me that there were many disadvantages attending this method of study, as having faulty originals, etc.; and even when the pictures or prints to be imitated were by the best masters, it was little more than pouring water out of one vessel into another. Drawing in an academy, though it should be after the life, will not make the student an artist; for as the eye is often taken from the original to draw a bit at a time, it is possible he may know no more of what he has been copying when his work is finished than he did before it was begun.

"There may be, and I believe are, some who, like the engrossers of deeds, copy every line without remembering a word; and if the deed should be in law Latin or old French, probably without understanding a word of their original,—happy is it for them, for to retain would be indeed dreadful.

"A dull transcriber who, in copying Milton's Paradise Lost, hath not omitted a line, has almost as much right to be compared to Milton as an exact copier of a fine picture by Rubens hath to be compared to Rubens. In both cases the hand is employed about minute parts, but the mind scarcely ever embraces the whole. Besides this, there is an essential difference between the man who transcribes[18] the deed and he who copies the figure; for though what is written may be line for line the same with the original, it is not probable that this will often be the case with the copied figure: frequently far from it. Yet the performer will be much more likely to retain a recollection of his own imperfect work than of the original from which he took it.

"More reasons, not necessary to enumerate, struck me as strong objections to this practice, and led me to wish that I could find the shorter path; fix forms and characters in my mind, and, instead of copying the lines, try to read the language, and, if possible, find the grammar of the art, by bringing into one focus the various observations I had made, and then trying by my power on the canvas how far my plan enabled me to combine and apply them to practice.

"For this purpose I considered what various ways, and to what different purposes, the memory might be applied, and fell upon one which I found most suitable to my situation and idle disposition.

"Laying it down first as an axiom, that he who could by any means acquire and retain in his memory perfect ideas of the subjects he meant to draw, would have as clear a knowledge of the figure as a man who can write freely hath of the twenty-four letters of the alphabet and their infinite combinations (each of these being composed of lines), and would consequently be an accurate designer.

"This I thought my only chance for eminence, as I found that the beauty and delicacy of the stroke in engraving was not to be learnt without much practice, and demanded a larger portion of patience than I felt myself disposed to exercise. Added to this, I saw little probability of acquiring the full command of the graver in a sufficient degree to distinguish myself in that walk; nor was I, at twenty years of age, much disposed to enter on so barren and unprofitable a study as that of merely making fine lines. I thought it still more unlikely, that by pursuing the common method and copying old drawings, I could ever attain the power of making new designs, which was my first and greatest ambition. I therefore endeavoured to habituate myself to the exercise of a sort of technical memory; and by repeating in my own mind the parts of which objects were composed, I could by degrees combine and put them down with my pencil. Thus, with all the drawbacks which resulted from the circumstances I have mentioned, I had one material advantage over my competitors, viz. the early habit I thus acquired of retaining in my mind's eye, without coldly copying it on the spot, whatever I intended to imitate.[9][20] Sometimes, but too seldom, I took the life for correcting the parts I had not perfectly enough remembered, and then I transferred them to my compositions.

"My pleasures and my studies thus going hand in hand, the most striking objects that presented themselves, either comic or tragic, made the strongest impression on my mind; but had not I sedulously practised what I had thus acquired, I should very soon have lost the power of performing it.

"Instead of burdening the memory with musty rules, or tiring the eyes with copying dry and damaged pictures, I have ever found studying from nature the shortest and safest way of attaining knowledge in my art.[10] By adopting this method I found a redundancy of matter continually occurring. A choice of composition was the next thing to be considered, and my constitutional idleness[11] naturally led me to the use of such materials as I had previously collected; and to this I was further induced [21]by thinking that, if properly combined, they might be made the most useful to society, in painting, although similar subjects had often failed in writing and preaching.

"To return to my narrative: the instant I became master of my own time, I determined to qualify myself for engraving on copper. In this I readily got employment; and frontispieces to books, such as prints to Hudibras, in twelves, etc., soon brought me into the way. But the tribe of booksellers remained as my father had left them when he died about five years before this time,[12] which was of an illness occasioned partly by the treatment he met with from this set of people, and partly by disappointment from great men's promises; so that I doubly felt this usage, which put me upon publishing on my own account. But here again I had to encounter a monopoly of printsellers equally mean and destructive to the ingenious; for the first plate I published, called the 'Taste of the Town,' in which the reigning follies were lashed, had no sooner begun to take a[22] run, than I found copies of it in the print-shops, vending at half price, while the original prints were returned to me again; and I was thus obliged to sell the plate for whatever these pirates pleased to give me, as there was no place of sale but at their shops.

"Owing to this and other circumstances, by engraving, until I was near thirty, I could do little more than maintain myself; but even then I was a punctual paymaster."

The print here alluded to, I apprehend to be that now entitled the "Small Masquerade Ticket," or "Burlington Gate," published in 1724, in which the follies of the town are very severely satirized by the representation of multitudes, properly habited, crowding to the masquerade,[13] opera, pantomime of Doctor Faustus, etc., while the works of our greatest dramatic writers are trundled through the streets in a wheel-barrow, and cried as waste paper for shops.

As a further illustration of the taste of the times, the artist has given a view of Burlington Gate, with a figure, I believe, intended to represent the then fashionable artist, William Kent, on the summit, brandishing his palette and pencils, and placed in a more elevated situation than either Michael Angelo or Raphael, who, seated beneath, become the two supporters to this favourite of Lord Burlington.

To this popular artist, architect, and improver of gardens, Hogarth seems to have had an early dislike, founded in some degree on his being, as he really was, a most contemptible painter; and probably heightened by his ranking higher, with those who led the fashion of the day, than that very superior artist, Sir James Thornhill.

Hogarth the year following published his

which, combined with the inscription engraved beneath, is a very bitter satire on the painter; though it must be acknowledged that the original, which has been for many years in the vestry-room of St. Clement Danes, amply justifies the ridicule.

This picture produced a small tract, with the following title:—

"A letter from a parishioner of St. Clement Danes, to Edmund (Gibson), Lord Bishop of London, occasioned by his Lordship's causing the picture over the altar to be taken down, with some observations on the use and abuse of church paintings in general, and of that picture in particular."

In this tract, after some compliments to the prelate, the writer works himself into a violent rage at the introduction of this piece of popish foppery, and asks some questions which in a degree elucidate part of the inscription under Hogarth's copy:—

"To what end or purpose was it put there, but to affront our most gracious sovereign, by placing at our very altar the known resemblance of a person who is the wife of his utter enemy, and pensioner to the whore of Babylon?

"When I say the known resemblance, I speak not only according to my own knowledge, but appeal to all mankind who have seen the Princess Sobieski, or any picture or resemblance of her, if the picture of that angel in the white garment and blue mantle, which is there supposed to be beating time to the music, is not directly a great likeness of that princess.

"Whether it was done by chance or on purpose, I shall not determine; but be it which it will, it has given great offence, and your Lordship has acted [25]the part of a wise and good prelate to order its removal."

It was probably during the time of Hogarth's apprenticeship that he engraved the annexed print, entitled

I by no means think, as Mr. Nichols asserts, that this is one of the poorest of Hogarth's performances; for though slight, and not intended to be impressed on paper, the air of the figures is easy, and the faces, especially those of Sir Plume and the heroine of the story, extremely characteristic. It is said to have been engraven on the lid of a snuff-box for some gentleman characterized in Pope's admirable mock-heroic poem, probably Lord Petre, who is here represented as holding the lock of hair in his left hand. Sir Plume,—the round-faced and insignificant Sir Plume,—

"Of amber snuff-box justly vain,

And the nice conduct of a clouded cane;"

for Sir George Brown, who was the only one of the party that took the thing serious. He was angry that the poet should make him talk nothing but nonsense; and, in truth (as Mr. Warburton adds), one could not well blame him.

As this little story was intended to be viewed on[26] gold, the figures in the copy are not reversed, but left as they were originally engraven on the box; from which I believe there are only three impressions extant, one of which was sold by Greenwood at Mr. Gulston's sale, on the 7th of February 1786, for £33.

The following account of the persons for whom Hogarth painted several of his early pictures is copied from his own handwriting, and may sometimes be useful in tracing the pedigree of a portrait.

By this list, it appears that the two pictures of "Before and After" were painted for a Mr. Thomson; but as it is not probable that Hogarth delineated this subject twice, I think that these two pictures were the property of the late Lord Besborough. They were sold on his Lordship's demise, in February 1801, at Christie's rooms.

"Account taken, January 1, 1731, of all the pictures that remain unfinished.—Half payment received.

A family piece, consisting of four figures, for Mr. Rich, 1728.

An assembly of twenty-five figures, for Lord Castlemain, August 28, 1729.

Family of four figures; Mr. Wood, 1728.

A conversation of six figures; Mr. Cock, Nov. 1728.

A family of five figures; Mr. Jones, March 1730.

[27]The Committee of the House of Commons, for Sir Archibald Grant, Nov. 5, 1729.

The Beggar's Opera; ditto.

Single figure; Mr. Kirkham, April 18, 1730.

Family of nine; Mr. Vernon, Feb. 27, 1730.

Another of two; Mr. Cooper.

Another of five; Duke of Montague.

Two little pictures; ditto.

Single figure; Sir Robert Pye, Nov. 18, 1730.

Two little pictures, called "Before and After," for Mr. Thomson, Dec. 7, 1730.

A head, for Mr. Sarmond, Jan. 12, 1730-31.

Pictures bespoke for the present year 1731."

With this his memorandum ends; and I regret that he has not recorded the prices he received for the pictures. Mr. Nichols conjectures that they were originally very low; he is most probably right with respect to those that were painted in the early part of Hogarth's life. But let it be recollected that for the portrait of Garrick in Richard III. he received two hundred pounds, which, as the artist himself remarks, was a more liberal remuneration than had been paid to any contemporary painter. When my late friend Mr. Gainsborough began to paint portraits at Bath (at a period when much higher prices were paid), his general rule was five guineas for a three-quarters portrait.

Below is inserted a copy from one of Hogarth's early engravings, the arms of the Duchess of Kendal, mistress to George I., probably done on a piece of plate at the time he was Gamble's apprentice. The original, of the same size, is in the Editor's possession. It is drawn in a correct and spirited style; and considering the age of the artist, and the purpose for which it was engraven, not demanding much attention or exertion, gave some promise of the excellence which he afterwards attained.

In this point of view, to an admirer of Hogarth it becomes in some degree interesting, which will, I hope, plead my apology for the insertion of this solitary specimen of his boyish heraldry. On no other ground should so insignificant a production as a coat of arms have found a place in this volume.

MARRIES. PAINTS SMALL CONVERSATIONS, WHICH SUBJECTS HE QUITS FOR FAMILIAR PRINTS. ATTEMPTS HISTORY; BUT FINDING IT IS NOT ENCOURAGED IN ENGLAND, RETURNS TO ENGRAVING FROM HIS OWN DESIGNS. OCCASIONALLY TAKES PORTRAITS LARGE AS LIFE, FOR WHICH HE INCURS MUCH ABUSE. TO PROVE HIS POWERS AND VINDICATE HIS FAME, PAINTS THE ADMIRABLE PORTRAIT OF CAPTAIN CORAM, AND PRESENTS IT TO THE FOUNDLING HOSPITAL.

"I then married, and commenced painter of small conversation pieces, from twelve to fifteen inches high. This having novelty, succeeded for a few years. But though it gave somewhat more scope to the fancy, was still but a less kind of drudgery; and as I could not bring myself to act like some of my brethren, and make it a sort of a manufactory to be carried on by the help of background and drapery painters, it was not sufficiently profitable to pay the expenses my family required. I therefore turned my thoughts to a still more novel mode, viz. painting and engraving modern moral subjects, a field not broken up in any country or any age.

"The reasons which induced me to adopt this mode[30] of designing were, that I thought both writers and painters had, in the historical style, totally overlooked that intermediate species of subjects which may be placed between the sublime and grotesque; I therefore wished to compose pictures on canvas, similar to representations on the stage, and further hope that they will be tried by the same test, and criticised by the same criterion. Let it be observed, that I mean to speak only of those scenes where the human species are actors, and these I think have not often been delineated in a way of which they are worthy and capable.

"In these compositions, those subjects that will both entertain and improve the mind bid fair to be of the greatest public utility, and must therefore be entitled to rank in the highest class. If the execution is difficult (though that is but a secondary merit), the author has a claim to a higher degree of praise. If this be admitted, comedy in painting as well as writing ought to be allotted the first place, as most capable of all these perfections, though the sublime, as it is called, has been opposed to it. Ocular demonstration will carry more conviction to the mind of a sensible man, than all he would find in a thousand volumes; and this has been attempted in the prints I have composed. Let the decision be left to every unprejudiced eye; let the figures in either pictures or prints be considered as players dressed either for the sublime,—for[31] genteel comedy,[15] or farce,—for high or low life. I have endeavoured to treat my subjects as a dramatic writer: my picture is my stage, and men and women my players, who by means of certain actions and gestures are to exhibit a dumb show.

"Before I had done anything of much consequence in this walk, I entertained some hopes of succeeding in what the puffers in books call the great style of history painting; so that without having had a stroke of this grand business before, I quitted small portraits and familiar conversations, and with a smile at my own temerity, commenced history painter, and on a great staircase at St. Bartholomew's Hospital painted two Scripture stories (the 'Pool of Bethesda' and the 'Good Samaritan'), with figures seven feet high. These I presented to the charity,[16] and thought they might serve as a specimen to show that were there an inclination in England for encouraging historical pictures, such a first essay might prove the painting them more easily attainable than is generally imagined. But as religion, the great promoter of this [32]style in other countries, rejected it in England, I was unwilling to sink into a portrait manufacturer; and, still ambitious of being singular, dropped all expectations of advantage from that source, and returned to the pursuit of my former dealings with the public at large. This I found was most likely to answer my purpose, provided I could strike the passions, and by small sums from many, by the sale of prints which I could engrave from my own pictures, thus secure my property to myself.

"In pursuing my studies, I made all possible use of the technical memory which I have before described, by observing and endeavouring to retain in my mind lineally such objects as best suited my purpose; so that be where I would, while my eyes were open, I was at my studies, and acquiring something useful to my profession. By this means, whatever I saw, whether a remarkable incident or a trifling subject, became more truly a picture than one that was drawn by a camera-obscura. And thus the most striking objects, whether of beauty or deformity, were by habit the most easily impressed and retained in my imagination. A redundancy of matter being by this means acquired, it is natural to suppose I introduced it into my works on every occasion that I could.

"By this idle way of proceeding I grew so profane as to admire nature beyond the first productions of art, and acknowledged I saw, or fancied, delicacies in[33] the life so far surpassing the utmost efforts of imitation, that when I drew the comparison in my mind, I could not help uttering blasphemous expressions against the divinity even of Raphael Urbino, Correggio, and Michael Angelo. For this, though my brethren have most unmercifully abused me, I hope to be forgiven. I confess to have frequently said, that I thought the style of painting which I had adopted, admitting that my powers were not equal to doing it justice, might one time or other come into better hands, and be made more entertaining and more useful than the eternal blazonry and tedious repetition of hackneyed, beaten subjects, either from the Scriptures or the old ridiculous stories of heathen gods; as neither the religion of one or the other requires promoting among Protestants, as it formerly did in Greece, and at a later period in Rome.[17]

"For these and other heretical opinions, as I have before observed, I was deemed vain, and accused of enviously attempting what I was unable to execute.

"The chief things that have brought much obloquy[34] on me are: First, the attempting portrait-painting; Secondly, writing the Analysis of Beauty; Thirdly, painting the picture of 'Sigismunda;' and, Fourthly, publishing the first print of 'The Times.'

"In the ensuing pages it shall be my endeavour to vindicate myself from these aspersions, and each of the subjects taken in the order they occurred shall be occasionally interspersed with some thoughts by the way on the state of the arts, institution of a Royal Academy, Society of Arts, etc., as being remotely, if not immediately, connected with my own pursuits.

"Though small whole lengths and prints of familiar conversations were my principal pursuit, yet by those who were partial to me I was sometimes employed to paint portraits as large as life, and for this I was most barbarously abused. My opponents acknowledged, that in the particular branches to which I had devoted my attention I had some little merit; but as neither history nor portrait were my province, nothing but what they were pleased to term extreme vanity could induce me to attempt either one or the other; for it[35] would be interfering in that branch of which I had no knowledge, and in which I had therefore no concern.

"At this I was rather piqued, and, as well as I could, defended my conduct and explained my motives. Some part of this defence it will be necessary to repeat; and it will also be proper to recollect, that after having had my plates pirated in almost all sizes, I, in 1735, applied to Parliament for redress, and obtained it in so liberal a manner as hath not only answered my own purpose, but made prints a considerable article in the commerce of this country; there being now more business of this kind done here than in Paris, or anywhere else, and as well.

"The dealers in pictures and prints found their craft in danger by what they called a new-fangled innovation. Their trade of living and getting fortunes by the ingenuity of the industrious has, I know, suffered much by my interference; and if the detection of this band of public cheats and oppressors of the rising artists be a crime, I confess myself most guilty.

"To put this matter in a fair point of view, it will be necessary to state the situation of the arts and artists at this period. In doing which, I shall probably differ from every other author, as I think the books hitherto written on the subject have had a tendency to confirm prejudice and error, rather than[36] diffuse information and truth. My notions of painting differ not only from those who have formed their opinions from books, but from those who have taken them upon trust.

"I am therefore under the necessity of submitting to the public what may possibly be deemed peculiar opinions, but without the least hope of bringing over either men whose interests are concerned, or who implicitly rely upon the authority of a tribe of picture dealers and puny judges that delight in the marvellous, and determine to admire what they do not understand; but I have hope of succeeding a little with such as dare to think for themselves, and can believe their own eyes.

"As introductory to the subject, let us begin with considering that branch of the art which is termed still life—a species of painting which ought to be held in the lowest estimation.

"Whatever is or can be perfectly fixed, from the plainest to the most complicated object, from a bottle and glass to a statue of the human figure, may be denominated still life. Ship and landscape painting ought unquestionably to come into the same class; for if copied exactly as they chance to appear, the painters have no occasion of judgment; yet with those who do not consider the few talents necessary, even this tribe sometimes pass for very capital artists.

"'Well painted, and finely pencilled!' are phrases perpetually repeated by coach and sign painters. Merely well painted or pencilled is chiefly the effect of much practice; and we frequently see that those who are in these particulars very excellent cannot advance a step further.

"As to portrait-painting, the chief branch of the art by which a painter can procure himself a tolerable livelihood, and the only one by which a lover of money can get a fortune; a man of very moderate talents may have great success in it, as the artifice and address of a mercer is infinitely more useful than the abilities of a painter. By the manner in which the present race of professors in England conduct it, that also becomes still life as much as any of the preceding. Admitting that the artist has no further view than merely copying the figure, this must be admitted to its full extent; for the sitter ought to be still as a statue, and no one will dispute a statue being as much still life as fruit, flowers, a gallipot, or a broken earthen pan. It must, indeed, be acknowledged they do not seem ashamed of the title, for their figures are frequently so executed as to be as still as a post. Posture and drapery, as it is called, is usually supplied by a journeyman, who puts a coat, etc. on a wooden figure like a jointed doll, which they call a layman, and copies it in every fold as it chances to come; and all this is done at[38] so easy a rate, as enables the principal to get more money in a week than a man of the first professional talents can in three months. If they have a sufficient quantity of silks, satins, and velvets to dress their layman, they may thus carry on a very profitable manufactory without a ray of genius. There is a living instance well known to the connoisseurs in this town, of one of the best copiers of pictures, particularly those by Rubens, who is almost an idiot.[18] Mere correctness, therefore, if in still life, from an apple or a rose, to the face,—nay, even the whole figure, if you take it merely as it presents itself,—requires only an exact eye and an adroit hand. Their pattern is before them, and much practice with little study is usually sufficient to bring them into high vogue. By perpetual attention to this branch only, one should imagine they would attain a certain stroke—quite the reverse; for though the whole business lies in an oval of four inches long, which they have before them, they are obliged to repeat and alter the eyes, mouth, and nose, three or four times before they can make it what they think[39] right. The little praise due to their productions ought, in most cases, to be given to the drapery-man, whose pay is only one part in ten, while the other nine, as well as all the reputation, is engrossed by the master phiz-monger for a proportion which he may complete in five or six hours; and even this, little as it is, gives him so much importance in his own eyes, that he assumes a consequential air, sets his arms akimbo, and, strutting among the historical artists, cries, 'How we apples swim!'

"For men who drudge in this mechanical part merely for gain, to commence dealers in pictures is natural. In this, also, great advantage may accrue from the labour and ingenuity of others. They stand in the catalogue of painters; and having little to study in their own way, become great connoisseurs, not in the points where real perfection lies, for there they must be deficient, as their ideas have been confined to the oval; but their great inquiry is, how the old masters stand in the public estimation, that they may regulate their prices accordingly, both in buying and selling. You may know these painter-dealers by their constant attendance at auctions. They collect under pretence of a love for the arts, but sell, knowing the reputation they have stamped on the commodity they have once purchased, in the opinion of the ignorant admirer of pictures, drawings, and prints, which, thus warranted, almost in[40]variably produce them treble their original purchase money, and treble their real worth. Unsanctioned by their authority,[19] and unascertained by tradition, the best preserved and highest finished picture (though it should have been painted by Raphael) will not, at a public auction, produce five shillings; while a despicable, damaged, and repaired old canvas, sanctioned by their praise, shall be purchased at any price, and find a place in the noblest collections. All this is very well understood by the dealers, who, on every occasion where their own interest is concerned, are wondrously loquacious in adoring the mysterious beauties! spirited touches! brilliant colours! and the Lord knows what, of these ancient worn-out wonders! But whoever should dare to hint that (admitting them to be originally painted by Raphael) there is little left to admire in them, would be instantly stigmatized as vilifying the great masters, and, to invalidate his judgment, accused of envy and self-conceit. By these misrepresentations, if he has an independent fortune, he only suffers the odium; but if a young man, without any other property than his talents, presumes boldly to give an opinion, he may be undone by his temerity; for[41] the whole herd will unite and try to hunt him down.

"Such is the situation of the arts and artists at this time. Credulity,—an implicit confidence in the opinions of others,—and not daring to think for themselves, leads the whole town into error, and thus they become the prey of ignorant and designing knaves.

"With respect to portrait-painting, whatever talents a professor may have, if he is not in fashion, and cannot afford to hire a drapery-man, he will not do; but if he is in vogue, and can employ a journeyman and place a layman in the garret of his manufactory, his fortune is made, and, as his two coadjutors are kept in the background, his own fame is established.

"If a painter comes from abroad, his being an exotic will be much in his favour; and if he has address enough to persuade the public that he had brought a new discovered mode of colouring, and paints his faces all red, all blue, or all purple, he has nothing to do but to hire one of these painted tailors as an assistant, for without him the manufactory cannot go on, and my life for his success.

"Vanloo,[20] a French portrait-painter, being told that the English were to be cajoled by any one who[42] had a sufficient portion of assurance, came to this country, set his trumpeters to work, and by the assistance of puffing monopolized all the people of fashion in the kingdom. Down went at once *,—*,—*,—*,—*,— etc. etc. etc.,[21] painters who before his arrival were highly fashionable and eminent, but by this foreign interloper were driven into the greatest distress and poverty.

"By this inundation of folly and fuss, I must confess I was much disgusted, and determined to try if by any means I could stem the torrent, and 'by opposing end it.' I laughed at the pretensions of these quacks in colouring, ridiculed their productions as feeble and contemptible, and asserted that it required neither taste nor talents to excel their most[43] popular performances. This interference excited much enmity, because, as my opponents told me, my studies were in another way. You talk, added they, with ineffable contempt of portrait-painting; if it is so easy a task, why do not you convince the world by painting a portrait yourself? Provoked at this language, I one day at the Academy in St. Martin's Lane put the following question: Supposing any man at this time were to paint a portrait as well as Vandyke, would it be seen or acknowledged, and could the artist enjoy the benefit or acquire the reputation due to his performance?

"They asked me in reply if I could paint one as well? and I frankly answered, 'I believed I could.'[22] My query as to the credit I should obtain if I did, was replied to by Mr. Ramsay, and confirmed by the president and about twenty members present: 'Our opinions must be consulted, and we will never allow it.' Piqued at this cavalier treatment, I resolved to try my own powers; and if I did what I attempted, determined to affirm that I had done it. In this decided manner I had a habit of speaking; and if I only did myself justice, to have adopted half words would have been affectation. Vanity, as I understand it, consists in affirming you have done that[44] which you have not done, not in frankly asserting what you are convinced is truth.

"A watchmaker may say, 'The watch which I have made for you is as good as Quare, or Tompion, or any other man could have made.' If it really is so, he is neither called vain nor branded with infamy, but deemed an honest and fair man for being as good as his word. Why should not the same privilege be allowed to a painter? The modern artist, though he will not warrant his works as the watchmaker, has the impudence to demand twice as much money for painting them as was charged by those whom he acknowledges his superiors in the art.

"Of the mighty talents said to be requisite for portrait-painting I had not the most exalted opinion, and thought that, if I chose to practise in this branch, I could at least equal my contemporaries, for whose glittering productions I really had not much reverence. In answer to this there are who will say with Peachum in the play, 'All professions be-rogue one another;' but let it be taken into the account that men with the same pursuits are naturally rivals, and when put in competition with each other must necessarily be so,—what racer ever wished that his opponent might outrun him? what boxer ever chose to be beat in pure complaisance to his antagonist? The artist who pretends to be pleased and gratified when he sees himself excelled by his competitor[45] must have lost all reverence for truth, or be totally dead to that spirit which I believe to be one great source of excellence in all human attempts; and if he is so polite and civil as to confess superiority in one he knows to be his inferior, he must be either a fool or an hypocrite, perhaps both. If he has temper enough to be silent, it is surely sufficient; but this I have seldom seen, even amongst the most complaisant and liberal of the faculty.

"Those who will honestly speak their feelings must confess that all this is natural to man. One of the highest gratifications of superiority arises from the pleasure which attends instructing men who do not know so much as ourselves; but when they verge on being rivals, the pleasure in a degree ceases. Hence the story of Rubens advising Vandyke to paint horses and faces, to prevent, as it is said, his being put in competition with himself in history-painting. Had either of these great artists lived in England at this time, they would have found men of very moderate parts—mere face painters—who, if they chanced to be in vogue, might with ease get a thousand a year, when they with all their talents would scarcely have found employment.

"To return to my dispute with Mr. Ramsay on the abilities necessary for portrait-painting: as I found the performances of professors in this branch of the art were held in such estimation, I determined to[46] have a brush at it. I had occasionally painted portraits; but as they required constant practice to take a likeness with facility, and the life must not be rigidly followed, my portraitures met with a fate somewhat similar to those of Rembrandt. By some they were said to be nature itself, by others declared most execrable; so that time only can decide whether I was the best or the worst face painter of my day, for a medium was never so much as suggested.

"The portrait which I painted with most pleasure, and in which I particularly wished to excel, was that of Captain Coram, for the Foundling Hospital; and if I am so wretched an artist as my enemies assert, it is somewhat strange that this, which was one of the first I painted the size of life, should stand the test of twenty years' competition, and be generally thought the best portrait in the place, notwithstanding the first painters in the kingdom exerted all their talents to vie with it.[23] To this I refer Mr. Rams-eye[24] and his quick-sighted and impartial coadjutors."

was born in the year 1668, bred to the sea, and passed the first part of his life as master of a vessel trading to the colonies. While he resided in the vicinity of Rotherhithe, his avocations obliging him to go early into the city and return late, he frequently saw deserted infants exposed to the inclemencies of the seasons, and through the indigence or cruelty of their parents left to casual relief or untimely death. This naturally excited his compassion, and led him to project the establishment of an hospital for the reception of exposed and deserted young children; in which humane design he laboured more than seventeen years, and at last, by his unwearied application, obtained the Royal Charter, bearing date the 17th of October 1739, for its incorporation.

He was highly instrumental in promoting another good design, viz. the procuring a bounty upon naval stores imported from the colonies to Georgia and Nova Scotia. But the charitable plan which he lived to make some progress in, though not to complete, was a scheme for uniting the Indians in North America more closely with the British Government,[48] by an establishment for the education of Indian girls. Indeed, he spent a great part of his life in serving the public, and with so total a disregard to his private interest, that in his old age he was himself supported by a pension of somewhat more than an hundred pounds a year,[25] raised for him at the solicitation of Sir Sampson Gideon and Dr. Brocklesby, by the voluntary subscriptions of public-spirited persons, at the head of whom was the late Frederick Prince of Wales. On application being made to this venerable and good old man to know whether a subscription being opened for his benefit would not offend him, he gave this noble answer: "I have not wasted the little wealth of which I was formerly possessed in self-indulgence or vain expenses, and am not ashamed to confess that in this my old age I am poor."

This singularly humane, persevering, and memorable man died at his lodgings near Leicester Square, March 29, 1751, and was interred, pursuant to his own desire, in the vault under the chapel of the Foundling Hospital, where an historic epitaph records his virtues, as Hogarth's portrait has preserved his honest countenance.

Hogarth thus resumes his narrative:—

"For the portrait of Mr. Garrick in Richard III. I was paid two hundred pounds[26] (which was more than any English artist ever received for a single portrait), and that, too, by the sanction of several painters who had been previously consulted about the price, which was not given without mature consideration.

"Notwithstanding all this, the current remark was, that portraits were not my province, and I was tempted to abandon the only lucrative branch of my art, for the practice brought the whole nest of phiz-mongers on my back, where they buzzed like so many hornets. All these people have their friends, whom they incessantly teach to call my women harlots, my 'Essay on Beauty' borrowed,[27] and my composition and engraving contemptible.

"This so much disgusted me, that I sometimes declared I would never paint another portrait, and frequently refused when applied to; for I found by mortifying experience, that whoever would succeed [50]in this branch must adopt the mode recommended in one of Gay's fables, and make divinities of all who sit to him.[28] Whether or not this childish affectation will ever be done away, is a doubtful question: none of those who have attempted to reform it have yet succeeded; nor, unless portrait-painters in general become more honest, and their customers less vain, is there much reason to expect they ever will."

Though thus in a state of warfare with his brother artists, he was occasionally gratified by the praise of men whose judgment was universally acknowledged, and whose sanction became an higher honour, from its being neither lightly nor indiscriminately given.[51] The following letter from the facetious Mr. George Faulkner notices the estimation in which the author of The Battle of the Books held the painter of "The Battle of the Pictures:"—

To Mr. William Hogarth, at his house in Leicester Fields, London.

"Sir,—I was favoured with a letter from Mr. Delany, who tells me that you are going to publish three prints.[29] Your reputation here is sufficiently known to recommend anything of yours, and I shall be glad to serve you. The duty on prints is ten per cent. in Ireland. You may send me fifty sets, provided you will take back what I cannot sell. I desire no other profit than what you allow in London to those who sell them again. I have often the favour of drinking your health with Doctor Swift, who is a great admirer of yours, and hath made mention of you in his poems with great honour,[30] and desired me [52]to thank you for your kind present, and to accept of his service.—I am, Sir, your most obedient and most humble servant,

"George Faulkner.

"Dublin, Nov. 15, 1740."

Hogarth about this time painted the portrait of Dr. Benjamin Hoadley, Bishop of Winchester, which, though rather French, is in a grand style. Concerning it, Dr. John Hoadley wrote the following whimsical epistle to the artist:—

To Mr. Wm. Hogarth.

"Dear Billy.—You were so kind as to say you would touch up the Doctor if I would send it to town. Lo! it is here. I am at Alresford for a day or two, to shear my flock and to feed 'em (money, you know, is the sinews of war); and having this morning taken down all my pictures, in order to have my room painted, I thought I might as well pack up Dr. Benjamin, and send him packing to London. My love to him, and desire him, when his wife says he looks charmingly, to drive immediately to Leicester[53] Fields (Square I mean, I beg your pardon), and sit an hour or two, or three, in your painting-room. Do not set it by and forget it now,—don't you. My humble service waits upon Mrs. Hogarth, and all good wishes upon your honour; and I am, dear Sir, your obliged and affectionate

"J. Hoadley."

OF ACADEMIES. HOGARTH'S OPINION OF THAT NOW DENOMINATED ROYAL; AND OF THE SOCIETY FOR THE ENCOURAGEMENT OF ARTS, MANUFACTURES, AND COMMERCE, GIVING PREMIUMS FOR PICTURES AND DRAWINGS.

Among Hogarth's loose papers I found the rough draft of a letter (addressed but not directed) to a nobleman, declaring his disapprobation of a scheme by which certain projectors were endeavouring to establish a Royal Academy, and stating that he had a plan which would be much more useful. I do not know that he ever sent the epistle, or admitting he did, that it was honoured with an answer. But as I think it probable he had given the subject some consideration, with the hope of bringing his project to bear, and that in the following pages relative to the Royal Academy he has stated what he meant to have said to the Peer, I have inserted it:—

"My Lord,—Mr. Martin has informed me that when some of my thoughts relative to the establish[55]ment of a public academy are put into writing, you will peruse them. I have made a rough sketch, but to fit it for inspection will require much time, which it will be needless to take till I have your Lordship's opinion on two or three leading points on which the whole will turn, and which I cannot with propriety commit to paper. A verbal statement of them will not take up more than half an hour; and if, when known, they are not concurred in, I will not take up your Lordship's time by arguing on their propriety. But I am vain enough to think, that though I must say strong, and perhaps startling things, with regard to myself and others, I can prove every position which I shall advance.

"I have reason to believe that another project is in hand: this the author will naturally defend in opposition to mine, but it shall not create controversy; for being now upwards of sixty years of age, and in a very poor state of health, I would rather lose a favourite point than break a night's rest.

"Mr. Ramsey, if I judge right, is no stranger to the plan I allude to, and I know his opinion differs from mine, and am firmly persuaded his interest will induce him to support it.—I am, my Lord, etc.,

"W. H."

"Much has been said about the immense benefit likely to result from the establishment of an academy[56] in this country; but as I do not see it in the same light with many of my contemporaries, I shall take the freedom of making my objections to the plan on which they propose forming it; and as a sort of preliminary to the subject, state some slight particulars concerning the fate of former attempts at similar establishments.

"The first place of this sort was in Queen Street, about sixty years ago; it was begun by some gentlemen-painters of the first rank, who in their general forms imitated the plan of that in France, but conducted their business with far less fuss and solemnity; yet the little that there was, in a very short time became the object of ridicule. Jealousies arose, parties were formed, and the president and all his adherents found themselves comically represented as marching in ridiculous procession round the walls of the room. The first proprietors soon put a padlock on the door; the rest, by their right as subscribers, did the same, and thus ended this academy.

"Sir James Thornhill, at the head of one of these parties, then set up another in a room he built at the back of his own house,—now next the playhouse,—and furnished tickets gratis to all that required admission; but so few would lay themselves under such an obligation, that this also soon sunk into insignificance. Mr. Vanderbank headed the rebellious party, and converted an old Presbyterian meeting-house[57] into an academy, with the addition of a woman figure, to make it the more inviting to subscribers. This lasted a few years; but the treasurer sinking the subscription money, the lamp, stove, etc. were seized for rent, and that also dropped.

"Sir James dying, I became possessed of his neglected apparatus; and thinking that an academy conducted on proper and moderate principles had some use, proposed that a number of artists should enter into a subscription for the hire of a place large enough to admit thirty or forty people to draw after a naked figure. This was soon agreed to, and a room taken in St. Martin's Lane. To serve the society, I lent them the furniture which had belonged to Sir James Thornhill's academy; and as I attributed the failure of that and Mr. Vanderbank's to the leading members assuming a superiority which their fellow-students could not brook, I proposed that every member should contribute an equal sum to the establishment, and have an equal right to vote in every question relative to the society. As to electing presidents, directors, professors, etc., I considered it as a ridiculous imitation of the foolish parade of the French Academy, by the establishment of which Louis XIV. got a large portion of fame and flattery on very easy terms. But I could never learn that the arts were benefited, or that members acquired any other advantages than what arose to a few leaders[58] from their paltry salaries, not more I am told than £50 a year; which, as must always be the case, were engrossed by those who had most influence, without any regard to their relative merit.[31] As a proof of the little benefit the arts derived from this Royal Academy, Voltaire asserts that, after its establishment, no one work of genius appeared in the country: the whole band, adds the same lively and sensible writer, became mannerists and imitators.[32] It may be said in answer to this, that all painting is but imitation. Granted; but if we go no further than copying what has been done before, without entering into the spirit, causes, and effects, what are we doing? If we vary from our original, we fall off from it, and it ceases to be a copy; and if we strictly adhere to it, we can have no hopes of getting beyond it; for 'if two men ride on a horse, one of them must be behind.'

[59]"To return to our own academy. By the regulations I have mentioned of a general equality, etc., it has now subsisted near thirty years, and is, to every useful purpose, equal to that in France, or any other; but this does not satisfy. The members, finding his present Majesty's partiality to the arts, met at the Turk's Head in Gerard Street, Soho, laid out the public money in advertisements to call all sorts of artists together, and have resolved to draw up and present a ridiculous address to King, Lords, and Commons to do for them what they have (as well as it can be) done for themselves. Thus to pester the three great estates of the empire, about twenty or thirty students, drawing after a man or a horse, appears, as it must be acknowledged, foolish enough; but the real motive is, that a few bustling characters, who have access to people of rank, think they can thus get a superiority over their brethren, be appointed to places, and have salaries as in France, for telling a lad when an arm or a leg is too long or too short.

"Not approving of this plan, I opposed it; and having refused to assign to the society the property which I had before lent them, I am accused of acrimony, ill-nature, and spleen, and held forth as an enemy to the arts and artists. How far their mighty project will succeed, I neither know nor care; certain I am it deserves to be laughed at, and laughed at it[60] has been.[33] The business rests in the breast of Majesty, and the simple question now is, whether he will do what Sir James Thornhill did before him, i.e. establish an academy with the little addition of a royal name, and salaries for those professors who can make most interest and obtain the greatest patronage. As his Majesty's beneficence to the arts will unquestionably induce him to do that which he thinks most likely to promote them, would it not be more useful if he were to furnish his own gallery with one picture by each of the most eminent painters among his own subjects? This might possibly set an example to a few of the opulent nobility; but even then it is to be feared that there never can be a market in this country, for the great number of works which, by encouraging parents to place their children in this line, it would probably cause to be painted. The world is already glutted with these commodities, which do not perish fast enough to want such a supply.

"In answer to this and other objections which I have sometimes made to those who display so much zeal for increasing learners, and crowding the profession,[61] I am asked if I consider what the arts were in Greece, what immense benefits accrued to the city of Rome from the possession of their works, and what advantages the people of France derive from the encouragement given by their Royal Academy? It is added, why cannot we have one on the same principles? That we may not be led away by sounds without meaning, let us take a cursory view of these things separately, and in the same order that they occurred.

"The height to which the arts were carried in Greece was owing to a variety of causes, concerning some of which we can now only form conjectures. They made a part of their system of government, and were connected with their modes of worship. Their temples were crowded with deities of their own manufacture, and in places of public resort were depicted such actions of their fellow-citizens as deserved commemoration; which, being displayed in a language legible to all, incited the spectator to emulate the virtues they represented. The artists who could perform such wonders were held in an estimation of which we can hardly form an idea; and could we ascertain the rewards they received, I think it would be found that they were most liberally paid for their works, and might therefore devote much more time than we can afford to rendering them perfect.