The Project Gutenberg EBook of The White House (Novels of Paul de Kock Volume XII), by Charles Paul de Kock This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The White House (Novels of Paul de Kock Volume XII) Author: Charles Paul de Kock Release Date: September 8, 2012 [EBook #40712] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WHITE HOUSE *** Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

Copyright 1904 by G. Barrie & Sons

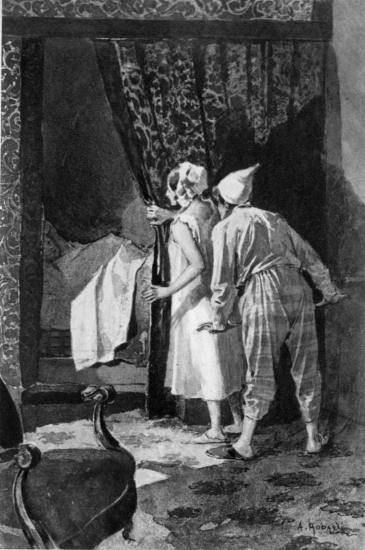

AN UNLOOKED-FOR INTRUDER

As Cornélie was about to draw the curtains aside, she stopped, fell back a step or two, turned pale and said: ... "It seems to me that I hear someone breathing."

THE JEFFERSON PRESS

BOSTON NEW YORK

Copyrighted, 1903-1904, by G. B. & Sons.

I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII, XIX, XX, XXI, XXII, XXIII, XXIV, XXV, XXVI, XXVII, XXVIII, XXIX, XXX, XXXI, XXXII, XXXIII

It was mid-July in the year eighteen hundred and twenty-five. The clock on the Treasury building had just struck four, and the clerks, hastily closing the drawers of their desks, replacing documents in their respective boxes and pens on their racks, lost no time in taking their hats and laying aside the work of the State, to give all their attention to private business or pleasure.

Amid the multitude of persons of all ages who thronged the long corridors, a gentleman of some twenty-seven or twenty-eight years, after arranging his knives, his pencils and his eraser much more methodically than young men are accustomed to do, and after carefully brushing his hat and coat, placed under his arm a large green portfolio, which at a little distance might have been mistaken for that of the head of a department, and assuming an affable, smiling expression, he joined the crowd that was hurrying toward the door, saluting to right and left those of his colleagues who, as they passed him, said:

"Bonjour, Robineau!"

Monsieur Robineau—we know his name now—when he was a hundred yards or more from the department, suddenly adopted an altogether different demeanor; he seemed to swell up in his coat, raised his head and ostentatiously quickened his pace; the amiable smile was replaced by a busy, preoccupied air; he held the great portfolio more closely to his side and glanced with a patronizing expression at the persons who passed him. His manner was no longer that of a simple clerk at fifteen hundred francs; it was that of a chief of bureau at least.

However, despite his haughty bearing, Robineau bent his steps toward a modest restaurant, where a dinner was served for thirty-two sous, which he considered delicious, because his means did not allow him to procure a better one. Herein, at all events, Robineau displayed great prudence; to be able to content oneself with what one has, is the best way to be happy; and since we hear the rich complain every day, the poor must needs appear to be satisfied.

But as he crossed the Palais-Royal garden on the way to his restaurant, Robineau was halted by two very fashionably dressed young men who laughingly barred his path. One, who seemed to be about twenty-four years of age, was tall and thin and stooped slightly, as tall men who are not in the military service are likely to do. Despite this trifling defect in his figure he bore himself gracefully; there was in his manners and in his slightest movements an abandon instinct with frankness, and a fascinating vivacity. His attractive face, his large blue eyes, and his golden hair, which fell gracefully about his high, aristocratic forehead, combined to make of this young man a most comely cavalier; but his pallor, the strongly marked lines under his eyes, and the customary expression of his features, denoted a young man who had taken a great deal out of life and who was already old in the matter of sensations and pleasures.

His companion was shorter and his features were less regular, but he would have been called perhaps a comelier youth. His hair was black, his eyes, albeit very dark brown, had an attractively sweet expression, and his voice and his smile finished what his eyes had begun. There was less joviality, less vivacity in his manners than in his friend’s; but he did not appear, like him, to be already sated with all the enjoyments that life offers.

At sight of the two young men, the clerk’s face became amiable once more; he eagerly grasped the hand that the taller, fair-haired one offered him, and cried:

"Ah! it is Alfred de Marcey! Delighted to meet you.—And Monsieur Edouard! You are both well, I see.—You are going to dine, doubtless; and so am I."

That one of the two young men whose hand Robineau continued to shake, and whose noble and intelligent face denoted none the less a slight tendency to raillery, looked at our clerk with a smile; and there was in that smile a lurking expression of mischief at which a very sensitive person might have taken offence, had it not been that he instantly exclaimed in a cordial, merry tone:

"Dear Robineau!—Where on earth have you been of late?—My friend, such high-crowned hats are not worn now. Fie! that is last year’s style; but I suppose you wear it to add to your height, eh? And those coat-tails!—Ha! ha! You look like a noble father. Who in the devil makes your clothes? Do you know that you are half a century behind the times?"

Robineau took all these jesting remarks in very good part; and, releasing the young man’s hand at last, he rejoined good-humoredly:

"It’s a very easy matter for you gentlemen, rich as you are, with your fifty, or a hundred thousand francs a year, to follow all the fashions, to be on the watch for the slightest change in the cut of a coat or the shape of a hat; but a simple government clerk, who has only his salary of a hundred louis!—However, I must be promoted soon.—You can see that one must be orderly and economical, if one doesn’t want to run into debt. And then, I never paid much attention to my dress! I am not coquettish myself. Mon Dieu! so long as a man is dressed decently, what does it matter, after all, that a coat is a little longer or shorter?"

"Ah! you play the philosopher, Robineau! But what about those most symmetrical curls which you arrange so carefully on each side of your face?"

"Oh! those are natural! I never touch them."

"Nonsense! I’ll wager that you never go to bed without rolling your hair in curl-papers!"

"Well! upon my word!"

"Oh! I know you—with your assumption of indifference! It’s just as it used to be at school: it made little difference to you what you had for dinner; but the next day you would play sick in order to get soup."

As he spoke, the tall young man turned toward his friend, who could not help smiling; while Robineau, to change the subject, hastily addressed the latter.

"Well, Monsieur Edouard, how goes the literary career, the drama? Successful as always, of course? You are used to that."

Edouard made a faint grimace, and Alfred roared with laughter, crying:

"Ah! you were well-advised to talk to him of success! You have no idea what chord you have touched!—What, Robineau! have you not divined from that long face, that frowning brow, a poet who has met with an accident? who has been victimized by a cabal? That, in a word, you are looking upon a fallen author?"

"The deuce! is it so?—What! Monsieur Edouard, have you had a fall?"

"Yes, monsieur," Edouard replied, with a faint sigh.

"Ah! that is amusing!"

"You consider it amusing, do you?"

"I meant to say, extraordinary—for you have sometimes succeeded.—Was it very bad then?—that is to say, didn’t it take?"

"It seems not, as it was hissed."

"Faith! I don’t know what sort of a play yours was, but I am sure that it couldn’t be any worse than the one I saw the day before yesterday at Feydeau. Fancy! a perfect rigmarole! all entrances and exits; in fact, it was so stupid, that I, who almost never hiss, could not help doing as the others did. I hissed like a rattlesnake."

Alfred, who for several minutes had been restraining a fresh inclination to laugh, dropped his friend’s arm and gave full vent to his hilarity, while Edouard said to Robineau, with an expression which he strove to render resigned:

"I thank you, monsieur, for having helped to bury my work."

"What? can it be that it was yours?" said Robineau, opening his little black eyes as wide as possible.

"Yes, indeed!" said Alfred, "it was his play that you hissed like a rattlesnake."

"Oh! mon Dieu! how sorry I am! If I could have guessed! But it’s your own fault too; if you had sent me a ticket, it would not have happened. I remember now that there were some very clever mots—some pretty scenes. I am really distressed, Monsieur Edouard."

"And I assure you that I am not in the least offended. What do a few hisses more or less matter?—And in my opinion, a good hard fall is better than to drag along through two or three performances."

"Then you bear me no grudge?"

"Why, no," said Alfred, "you have proved your friendship! he who loves well, chastises soundly! Moreover, the best general sometimes loses a battle. Isn’t that so, Edouard?—Look you, I’ll wager that that has been said to you at least fifty times since the night before last."

Edouard smiled—but this time with a good heart; and he once more took his friend’s arm, who looked at Robineau again, while a mocking smile played about his lips.

"You are still very busy, Robineau?"

"Oh, yes! always! We have an infernal amount of work to do. My chief relies on me; he knows that in moments of stress I am always on hand."

"What have you in that big portfolio that you hold so tight under your arm? Are you to play the part of a notary to-night?"

"Oh! it has nothing to do with acting; it’s work I am taking home."

"The devil!"

"Very important work. I sometimes spend a good part of the night on it. But I am certain of promotion."

Alfred made no reply to this; he bit his lips and glanced at Edouard, and a moment later he continued:

"And the love-affairs, Robineau—how do they come on? How many mistresses have you at this moment?"

"Oh! I am virtuous, very virtuous.—In the first place, my means do not permit me to keep women; in the second place, even if I had the means, I wouldn’t do it—my tastes don’t run that way. I insist upon being loved for myself!"

"You certainly deserve to be adored, monsieur."

"I don’t say that I wish to be adored precisely; but I desire to find that sympathy—that sweet unreserve—that—Oh! you are laughing! You don’t believe in true love!"

"I? on the contrary, I believe in whatever you choose; and the proof of it is that I really believe myself to be in love with all the pretty women I meet—eh, Edouard?—Oh! but we mustn’t mention women to him now."

"What’s that? has he had a fall with them too?" said Robineau, chuckling as if well pleased with his jest.

"No; but his latest passion has just executed a fugue with an Englishman; so that Edouard swears that he will never become attached to another sempstress."

"Aha! so she was a sempstress?—And I’ll be bound that you denied her nothing; for you are very open-handed. And then she planted you for some wretched Englishman who promised her a carriage. That is the reward of wasting one’s substance on a woman!"

"On whom would you have us waste it, pray, Robineau? So far as I am concerned, women have often deceived me; but I bear them no ill-will. For, after all, a woman, when she throws us over, leaves us at liberty to take another; whereas we often don’t know how to rid ourselves of one who is faithful."

"That is the reasoning of a jilt!" said Edouard. "Ah! my dear Alfred, you will always be lucky in love, for you will never love!"

"That is so," said Robineau; "he cares nothing for sentiment, he is all for pleasure; and when one is in his position, rich, of noble birth and an only son, with a father who lets him do whatever he pleases, there is no lack of pleasure. For my part, messieurs, I know how to restrict myself; and then, as I told you, I have simple tastes—I care neither for luxury, nor for honors.—What do I need, to be happy?—What I have: a good place—a little fatiguing, to be sure, but I am fond of work—and pending the time when I shall marry, a pretty, emotional, loving mistress, who doesn’t cost me a sou, and on whose fidelity I can rely; for I am horribly jealous."

"And where do you find such a treasure, Robineau?"

"They are easily found; to be sure, I do not apply to grisettes or working-girls.—But I beg pardon, messieurs; while chatting with you, I forget that I am expected to dine at a house to which I was invited a week ago. They will not sit down without me, and I do not wish to keep them waiting too long."

As he spoke, Robineau stepped toward Alfred to shake hands. The latter seized the opportunity to take possession of the portfolio which the clerk held under his arm.

"My portfolio! my portfolio!" cried Robineau; "the devil! no practical jokes!"

"I’ll bet you that it contains nothing but blank paper," said Alfred, still retaining possession of the portfolio. "Come, Robineau; will you bet a dinner at Véry’s?"

"I won’t bet any dinner. I am in a hurry; give it back to me. I don’t want you to look inside; they are secret papers."

But Alfred paid no heed; he untied the strings of the portfolio, and exhibited to Edouard four packages of letter paper, three sticks of sealing wax, a pencil and two papers of pins.

"So this is what you work at all night?" observed Alfred; while Edouard laughed heartily at the expense of the man who had hissed his play.

Robineau feigned surprise, crying:

"Mon Dieu! I must have made a mistake! I took one package for another! I have so many files before me!—This vexes me terribly, I assure you; and if I were not expected at dinner, I would go back to my desk."

"Monseigneur, I restore your secret documents," said Alfred, handing the large portfolio, with an air of profound respect, to Robineau, who replaced it under his arm and was about to take his leave, to escape the witticisms of the two young men. But the taller one detained him.

"You are not angry, I trust, Robineau?"

"I! angry!—Why so, pray? You like to laugh and joke, and so do I, when I have time."

"Yes, I know that you are a good fellow at bottom. Look you—to prove to me that you bear me no grudge because I insisted upon casting a profane eye into the administrative portfolio, you must come to my house this evening; my father gives a large reception—I don’t quite know on what occasion; but this much I do know—that there will be cards and dancing and some very pretty women. Despite your little every-day passion, you are a connoisseur of the sex, and you must come. Edouard will be with us—he has promised me; we will win his money at écarté, and that will help him to forget his last failure. And then, who knows? perhaps he will find among the company a beauty who will wipe from his heart the memory of his faithless fair.—Well! will you come?"

Robineau’s face fairly beamed while Alfred proffered his invitation; he grasped his hand again and shook it hard, as he replied:

"My dear friend—certainly—I am deeply touched. This courteous invitation——"

"Enough fine phrases! Is there any need of ceremony between us? I intended to write to you; but you know how thoughtless I am, and I forgot all about it.—Then you will come?"

"I most certainly shall have that honor, and I am——"

"All right, it’s understood; until this evening, then; and we will try to enjoy ourselves, which is not always easy at grand functions."

With that the young man and his companion, after nodding to the Treasury clerk, walked rapidly away, leaving Robineau in the garden of the Palais-Royal, so engrossed by the invitation he had just received and by the prospect of passing the evening at the Baron de Marcey’s, that, if his feet had not been arrested by the raised rim of the basin, he would have walked straight into the water on the way to his favorite restaurant.

Robineau arrived at last at his modest restaurant, the public rooms of which were, as usual, full of people; for small purses are more common than large fortunes; which does not mean that only the wealthy frequent the best restaurants. But one thing is certain, namely, that at thirty-two sou places, the patrons eat with heartier appetites than one sometimes has in the gilded salons of the others. As bread is supplied in unlimited quantities, the consumers do not stint themselves with respect to it; and the cry of: "Some bread, waiter!" is heard constantly from every part of the room.

Robineau, who, under ordinary circumstances, was not of the number of small eaters, had less appetite than usual on this day; he swallowed his soup without complaining that it was too clear or too salt, to the waiter’s great surprise; and when the latter inquired what he wished to eat after the soup, Robineau replied:

"Whatever you please, but make haste. I am in a great hurry. I am going to the Baron de Marcey’s this evening, and I must dress with great care."

"In that case, monsieur, a beefsteak and potatoes," said the waiter, who cared very little whether his customer was going to a baron’s that evening, while Robineau looked about with an air of importance to see whether anyone had noticed what he had just said, and whether people were looking at him with more respect. But to no purpose did he cast his eyes over the neighboring tables; the persons who surrounded him were too busily occupied in putting out of sight what was on their plates, to amuse themselves staring at their neighbors; a thirty-two sou restaurant is not the place in which to put on airs.

Robineau, seeing that no one paid any attention to him, although he mentioned the baron’s name once more, hastened to eat the three courses which followed the soup. When the waiter came with the dessert, which consisted of nuts and raisins, Robineau’s customary order, the clerk sprang to his feet, and, placing his portfolio under his arm, left the table, saying to the waiter:

"That’s for you; it’s your pourboire."

Then he walked hurriedly through the dining-room, elbowing such customers as stood in his path, who grumbled at his lack of ceremony; while the waiter looked with a wry face at the nuts and raisins which were bestowed upon him as pourboire.

Robineau hastened to Rue Saint-Honoré, where his lodgings were situated. As he drew near the house, the ground floor of which was occupied by a milliner’s shop, he slackened his pace and his eyes seemed to try to pierce the yellow silk curtains which concealed the shop girls from the eyes of passers-by.

"The devil!" muttered Robineau; "it’s only six o’clock, and Fifine isn’t ready to leave the shop. But I am in extreme need of her assistance. If that thoughtless Alfred had written me a few days beforehand, I might have prepared for his grand reception, and I should have everything that I need. These rich people never remember that other people aren’t rich!—I don’t know whether I have a white waistcoat to wear, and silk stockings.—Have I any silk stockings?—Mon Dieu! I lent them to Fifine the last night we went to the theatre, and she hasn’t returned them yet. That woman will end by stripping me of everything! I am too generous. But if she has worn holes in them I’ll make a terrible scene!—With fifteen hundred francs a year, when one has to feed and lodge oneself, and when one wishes to cut some figure in society, one cannot swim in silk stockings—it’s impossible!—and with all the rest, I have had no luck at écarté for some time past. Mon Dieu! when shall I be rich?—I certainly will not put on airs then; I will be neither haughty nor insolent. But at all events, when I receive an invitation to go into the best society, I shall not be driven to expedients to procure silk stockings."

While indulging in these reflections, Robineau had arrived in front of the shop; but the door was closed. To be sure, the curtains afforded a glimpse of the lower part of a face, an arm, or a profile; but there were six young women who worked in the shop; and when the mistress was present they kept their eyes on their work and did not attempt to look out of the windows. Robineau passed the door and decided to enter the passageway leading to his rooms, at the end of which was a door opening into the back shop. He walked to and fro for some time, coughing loudly when he was near the door at the end, and glancing impatiently at his silver watch, which he carried in his fob, at the end of a dainty blue ribbon of watered silk passed about his neck.

All six of the young women who worked in the milliner’s shop slept in the house; two in a room adjoining the mistress’s apartment, and the other four in a room on the fifth floor, above Robineau’s. Mademoiselle Fifine was one of the four. Robineau was well aware that, in order to go to her room, Fifine must pass through the passageway; but she did not ordinarily go up until nine o’clock, and he could not wait until that hour to speak to the girl. Much the simplest way would have been to go into the shop and ask Mademoiselle Fifine to step outside for a moment; but that would have meant an irrevocable quarrel with his fair one; for, like all milliner’s apprentices, Fifine had her own code of morals; if she had lovers, it was only because all her companions had their pleasant little acquaintances, and because they would have made fun of her if she too had not had someone to take her out to walk on Sunday. But during the week, madame—that was the title that they bestowed on the mistress of the establishment—was very strict with her young ladies, and she was responsible for their virtue from eight in the morning till nine at night.

After coughing vainly in the passage, Robineau decided to go up to his room, in order to put away his portfolio and make preparations for his toilet. He climbed the four flights of a dark and dusty staircase, of a type not uncommon on Rue Saint-Honoré; he entered his apartment, which consisted of two small rooms, one of which served as waiting-room, wardrobe and kitchen, the other as bedroom, dressing-room and salon. The first was scantily furnished, but the second was decorated with more or less taste, and it was orderly and clean; in fact, everything was in its place—a rare thing in a bachelor’s quarters.

Robineau opened one of the drawers of his commode, took out his black dress coat and his dancing trousers, and to his delight, found a spotlessly white piqué waistcoat. He spread them all on the bed, then looked at himself complacently in the mirror over the mantel; and his mirror showed him, as usual, a coarse, bloated face, small black eyes, a large round nose, a small mouth, a low forehead, very thick light hair, and thin, compressed lips. Robineau considered it a charming face; he smiled at himself, assumed affected poses, bowed to himself, and exclaimed:

"I am very good-looking, and in full-dress I ought to produce a great effect."

After looking at himself in the mirror for several minutes, he returned to his commode, fumbled in the drawers, turned everything upside down, and cried:

"Evidently I have no silk stockings. If worse comes to worst, I might buy a pair—I still have twenty-three francs left from my month’s pay; but that would straiten me; if I want to risk a little at écarté, I can’t do it. I know well enough that if I should ask Alfred to lend me money, he wouldn’t refuse; but I don’t want to appear to be short, and, in truth, as I have some very fine silk stockings, I don’t see why I should buy others. Mademoiselle Fifine simply must return them; if not, it’s all over, we are out, and I give her no more guitar lessons. She will think twice; a girl doesn’t find every day a lover who plays the guitar and who is obliging enough to teach his sweetheart how to play."

Robineau took down a guitar that hung in a corner of the room, went to the open window looking on the courtyard, and hummed a ballad, accompanying himself on the instrument. When Fifine was in her room on the fifth floor, the guitar was ordinarily the signal which notified her that Robineau awaited her; but it was hardly possible to hear the music in the shop.

After he had sung for some time, Robineau looked again at his watch; he stamped the floor impatiently and was about to go down to the passage, when someone rang at his door.

"It is she! She must have heard me!" he cried as he ran to open the door. But instead of his charmer, he found a young solicitor’s clerk, whom he knew as the friend of one of Fifine’s shopmates.

"Have they come up?" inquired the young man, not entering the room, but simply thrusting his head forward to look.

"What do you mean? have who come up?"

"The young ladies. I simply must speak to Thénaïs; I went up to their room at all risks and knocked; no one answered, but, as I came down, I heard your guitar; and knowing that you gave lessons to Mademoiselle Fifine, I thought that they were in your room."

"Alas, no! they are still in the shop; they won’t come up for a good hour at least; it is most annoying to me, for I have something very important to ask Fifine."

"Well! isn’t there any way to let them know that we are here?"

"Oh! if we should go to the shop, they would be angry; it’s expressly forbidden; and then I don’t care to do it myself; when one is in one of the departments of the government, one has to maintain a certain decorum; especially just now, we have to be moral; the rules are very strict on that point."

"We can get the young ladies to come out without going to the shop."

"Faith! it’s an hour since I came in, and began trying to think of a way to do it."

"Wait! I am never at a loss.—There’s no concierge in this house, is there?"

"No."

"So much the better—we can do what we please.—Have you two or three plates?"

"Plates? hardly; I very rarely eat in my room."

"No matter—a salad-bowl, a vase, anything you please."

Robineau looked in his buffet and returned with a porcelain preserve dish and one plate, saying:

"These are all I can find."

"Excellent," said the solicitor’s clerk, taking the two objects.

"What do you propose to do with them?"

"You will see; follow me, and shout as I do, with all your lungs, when we are near the shop."

The young man went slowly down stairs, holding the plate in one hand and the preserve dish in the other. Robineau followed, curious to see what he was going to do. When they reached the first floor, the clerk began to shout: "Stop thief!" and Robineau followed suit. Then the young man hurled the plate into the passage; whereupon Robineau ran after him to stop him.

"The devil!" he exclaimed, "that will do; don’t throw my preserve dish!"

But it was too late; the dish had already followed the plate; it broke into a thousand pieces, and at the crash all the young women rushed from the shop to inquire what was going on.

At sight of them, the solicitor’s clerk roared with laughter.

"I knew that I’d make you leave your work," he cried.

"Oh! it was a sell!" cried the shop-girls, with a laugh, while Robineau gazed sadly at the ruins of his preserve dish and murmured:

"Yes, it’s a very pretty scheme! But I won’t entrust any more of my dishes to this fellow."

The girls laughed uproariously; the young clerk was already talking with Mademoiselle Thénaïs, and Robineau was about to approach Fifine, when there was a cry of "Here’s madame!" whereupon the young milliners vanished like a flock of swallows, and the young men were once more alone in the passage.

"Well! now they have gone back again!" said Robineau.

"I told Thénaïs what I wanted to tell her," replied the other; and he left the house, enchanted with his ruse, while Robineau, who was minus a plate and preserve dish, and had not even spoken to Fifine, went upstairs to his room, consigning clerks and milliners to the devil. He arranged once more all the component parts of his costume, and had almost determined to go out to buy some silk stockings, when he heard two little taps at his door, and Mademoiselle Fifine appeared at last.

Fifine was a buxom, jovial wench of twenty-four, whose coloring was a little high, whose fair hair was of rather a doubtful shade, whose eyes were a little too prominent, and whose figure was a little too short; but there was a touch of decision in her manner which indicated a young woman of character, whom one might have taken for a roisterer, had she worn trousers.

"Well! what’s in the wind, my friend? What’s all this business of smashing dishes in order to see us? Dieu! what extravagance indeed! The girls called that very gallant!"

As she spoke, Fifine threw herself on a couch opposite the bed, and continued to eat cherries, which she carried in a handkerchief.

"If you think that it was an invention of mine, you are much mistaken!" rejoined Robineau sourly; "it was that little clerk, who, without a word to me—Don’t throw your stones all over my room, I beg you."

"I’ll sweep your room! Mon Dieu! Monsieur Neatness! Pray take care! he would rather have me swallow the stones, no matter what the result might be—eh, my dear friend?—What on earth is the matter with you to-night, Raoul? your nose is longer than usual; have you some secret trouble?"

"Oh! it’s nothing to laugh at."

"Well, I’m not inclined to cry. If you want me to cry, play me an act of melodrama; play me Monsieur Truguelin in Cœlina. When you come to the suicide, I’ll throw a cherry-stone at you."

"Come, Fifine, let us talk sense, I beg you."

"Come then and sit down beside me, so that I can pinch you. You see, I feel tremendously like pinching something to-night."

"I have no time to fool."

"Dieu! how agreeable this lover of mine is!"

"I am going to a reception this evening at my intimate friend Alfred de Marcey’s, son of the Baron de Marcey, who has nearly a hundred thousand francs a year."

"Ah! so that’s the reason one can’t look you in the face, and the reason you threw your dishes downstairs. Exactly! when one visits a baron, one shouldn’t eat next day. You’ve grown two inches already."

"Fifine, listen to me, I entreat you!"

"Are you going to cry?"

"To go to the Baron de Marcey’s, I must wear full evening dress."

"Ah! I see what you’re coming at—you want me to put on your curl-papers."

"Curl-papers—I shall be glad if you will, it is true; for you do it to perfection."

"Ah! the lion is quieting down!"

"But there is something else of which I am in urgent need, and that is my black silk stockings, which I lent you the last Sunday that it rained."

"Your silk stockings?"

"Yes, mademoiselle."

"The deuce! but they’re a long way off, if they’re still going!"

"What do you mean by that?"

"I mean that I lent them to Fœdora, to play in private theatricals, and she admitted that she let her best friend wear them the next day, to a wedding; but as his calves are exceptionally big, he ripped a few stitches when he took them off."

"Mon Dieu! this is what comes of lending your things!"

"Is a person to presume that her lover will ask her to return what he lends her?"

"Mademoiselle, I am not a capitalist, a dealer in novelties. I have never pretended to play the grand seigneur with you."

"Oh! anyone can see that!—Catch it, Raoul."

"Don’t throw cherry-stones at me, please.—What am I to do? It’s eight o’clock already; to be sure, I know that people go very late to large receptions."

"Sometimes they don’t go till the next day; it’s more comme il faut."

"But I counted on those stockings."

"You must buy some more; there’s a place across the street where they sell them."

"Buy some? Oh, yes! that’s very easy to say.—You shouldn’t have made me spend twelve francs at the restaurant last Sunday."

"We will spend fifteen next Sunday, my dear friend."

"You always want to eat the things that cost most."

"Nothing’s too good for me."

"Well, if I buy stockings, it’s adieu to our country excursion for Sunday, I warn you."

"That begins to move me.—Come, be calm, loulou; you’re very lucky to have a sweetheart with some imagination. Stay here and begin to dress at the top; I’ll go to look after the lower part!"[1]

"Oh! my dear Fifine, how good you will be to do that!"

"Give me five or six sheets of note paper—vellum."

"Here they are; as it happens, I have just brought some home from my office. Do you want some sealing-wax—three sticks?"

"Yes, yes, give it to me; I secure madame’s good graces with these things; otherwise she wouldn’t have let me come away so early; but I said that I had a sick-headache, and as I’m her favorite, she said: ‘Go upstairs to bed.’"

Fifine took the paper and sealing-wax, and skipped out of Robineau’s room; whereupon he began to undress, saying to himself:

"She is really an excellent girl, and as bright as a button, this Fifine! She’s a little hasty, and a bit of a glutton; but still she is mad over me and would jump into the fire for me. She has refused marquises, beet-sugar manufacturers and brokers for me; and yet I simply take her out on Sundays—that’s all. She isn’t like Monsieur Edouard’s sempstress, who left him for an Englishman.—Ha! ha! I am not so very sorry, for he seems rather inclined to put on airs. He has about three thousand francs a year, I believe; that’s not so much! But he writes plays, opéra-comiques, vaudevilles—that is to say, fragments of vaudevilles.—Mon Dieu! if I had the time, I would write plays, too; and I flatter myself they’d be done rather better than his. But when a man has to be at his desk from nine o’clock till four, and always working, how is he to cultivate the Muses? When I am chief of a bureau, or even deputy chief, then it will be different—I shall have some time to myself. That Alfred’s the lucky fellow! An only son, his father a baron, and about a hundred thousand francs a year!—And just see how it all came about: Alfred lost his mother when he was very young; his father married again some years later, and might have had other children; but he didn’t; instead of that, his wife, whom he adored, died three years after their marriage, and the baron, overwhelmed with grief by the loss of his second wife, swore that he would never marry again; and he has kept his oath, although he is still a young man.—How well it has all turned out for Alfred! Dieu! nothing like that will ever happen to me! And yet I have an uncle somewhere or other, careering round the world, according to what my mother told me before she died; an uncle who was determined to make his fortune, and who started for the Indies, or Peru—in fact, no one knows where. But psha! he has probably tried to leap Niagara! It’s only on the stage that uncles arrive just in time for the dénouement, in order to save innocence from going to prison. After all, I am not ambitious—I’m a philosopher, I am satisfied with what I have. If I had some silk stockings, though, I should be even better satisfied. But just let a fortune fall into my hands, and people will see how coolly, how phlegmatically I will receive it.—Well! here I am all undressed, and Mademoiselle Fifine doesn’t return.—I can’t put on my cravat before my feet are shod and my hair curled. Luckily it’s July, and I shan’t take cold."

To kill time, Robineau, being weary of walking about his room dressed like a person who is about to make bread, concluded to take his guitar. He had reached the second stanza of the romanza from Bélisaire, when he was interrupted by a burst of laughter. Fifine, having left the door ajar, had entered the room without making any noise, and was holding her sides as she contemplated Belisarius in his shirt.

"O Dieu! how handsome you are like that, my boy!" she said, still laughing; "I am tempted to call the girls to look at the picture."

"Call no one, I beg; although, without flattery, I believe I have a figure that wouldn’t frighten them."

"You look like a fat Bacchus."

"Let me see the stockings, please."

"Here they are, troubadour; and I think that they’ll make a handsome leg."

And Fifine tossed a pair of black silk stockings on Robineau’s knee. He examined them for some time, then cried:

"They’re a woman’s stockings!"

"To be sure, as it was Adeline who lent them to me."

"Men don’t wear openwork things like these."

"Bah! men wear something else, and it doesn’t prevent their dancing."

"But——"

"But these are all I could find, and it seems to me that you ought to be well satisfied."

Robineau concluded at last to put on the stockings.

"They’ll think that it’s a new style I am trying to introduce," he said.

While he began to dress, Fifine took the guitar and hummed a tune.

"So I shan’t have any lesson to-night, my friend?"

"You must see, my dear, that it’s impossible.—They fit me very well, these stockings—exceedingly well—it’s surprising! I have a leg that adapts itself to anything."

"By the way, do you remember the way we behaved last night?—Well! we had a most extraordinary scene! You know madame won’t let us read in bed, because she’s afraid of fire."

"She is quite right; as to that, I agree with her."

"That’s all right, but we girls don’t care a fig for her orders. Last night, after Fœdora had dictated a note to Thénaïs, and when Adeline had finished telling us how she detected her lover’s treachery—Oh! by the way, I never told you that story; it’s terribly funny!"

"My dear, if you would be good enough to put on my curl-papers now, I should——"

"The iron isn’t hot yet; it’s on the stove upstairs; no matter—give me some tissue paper, I’ll arrange you."

"Put on fifteen."

"Why not thirty-six, like another Ninon?—Look out now, don’t move!—Just imagine that Fidélio—that’s Adeline’s lover’s name—has a business agency office, and always keeps pretty little maid servants, who, they say, he’s in the habit of making love to. It’s so well known in the quarter, that they always tell a girl of it beforehand when she enters his service, so that she may know what to expect——"

"The iron——"

"Nonsense! don’t bother me with your iron!—Adeline didn’t know all that. The rascal had introduced himself to her under a false name. Ah! what villains men are! Instead of putting on curl-papers for you, I ought to tear all your hairs out, one by one!"

"Fifine—I beg you——"

"Don’t move.—But that isn’t all: Monsieur Fidélio, not satisfied with having a pretty blonde of twenty in his service, was making love to a married woman; and this married woman, it seems——"

"You are pulling my hair!"

"Oh! that, you know, is very bad! That a woman who is free should do what she pleases—that’s all right. But one either is bound or one isn’t—that’s all I know; that is to say, unless the husband’s a tyrant or a miser."

"It’s after nine o’clock, Fifine!"

"What’s the odds? you will have time enough to make conquests.—Now then, the servant noticed that the lady came very often to see Fidélio on business, and that Fidélio, instead of being pleasant with his maid, as he usually was, did nothing but scold her. But one can be a servant and still have lively passions; such things have been known. To revenge herself, the girl goes one fine day to the lady’s husband and offers to make him a witness of a meeting between his wife and her man of business. The husband was frantic; he accepted, sent for a cab, and got in with the little blonde, who was to tell the driver to stop at the proper time. But on the way—and this is the funniest part of it!—the husband began to find the little maid much to his liking and proposed to transfer his passion to her.—‘We are both deceived,’ says he; ‘let’s take our revenge together.’—She didn’t take to that scheme; she resisted and the man persisted. Tired of being urged by him,—he had entirely forgotten his wife,—she told the coachman to stop, opened the door, and jumped out of the cab. The gentleman jumped after her and broke his nose on the ground. The girl, to escape his attentions, entered the first house she came to. It happened to be ours; and who do you suppose she found in the passage?—who but Fidélio colloguing with Adeline!—Then there was an explosion, explanation, confusion, and——"

"The iron must be red hot!"

"I’ll go and fetch it; but if it isn’t hot, I won’t come down again."

Robineau looked at himself in the mirror, saying:

"When Fifine is in the mood for chattering, there’s no way to stop her. But she puts on curl-papers like an angel; I shall have the best dressed hair at the ball."

Fifine returned, carrying the curling-iron, smoking hot.

"Come quick; it isn’t too hot."

"It looks all red to me. My dear love, be careful not to burn me, I beseech you."

"Dieu! he’s a perfect little lamb when he’s frightened!—To return to our scene of last night: we had just gone to bed, and I was reading—because, without flattering myself, I am the best reader. Auguste had lent us the Barons von Felsheim, and we were devouring it—that is the word—when, in the middle of a charming chapter, someone knocked at our door, and we heard madame’s voice calling:—‘Mesdemoiselles, why have you a light burning so late?’—At that the most profound silence replaced our bursts of laughter, and to hide the light,—for we didn’t propose to put it out—it occurred to me to put a vessel—you know, a night vessel,—over the candle-stick. That worked very well; she couldn’t see anything. Madame called again, and we didn’t answer. Then madame went away; and when we thought she was back in her room, I took off the protecting vessel.—What do you suppose? The light was really out. We were in despair; we didn’t feel like sleeping, and we didn’t want to be left in the middle of a very interesting chapter, in which there’s something about truffles—and not a match, because we haven’t as yet saved up a sufficient sum to purchase that commodity, for milliner’s apprentices aren’t in the habit of patronizing savings banks. However, we were determined to have a light, and for my own part, I would have gone out and unhooked the street lantern rather than not finish my chapter. Just at that moment we heard your guitar and your voice. Ah! my dear, you have no idea of the effect that produced on us! You were an Orpheus, a demigod!—‘Not in bed yet!’ we shouted all together, and in an instant I was out of bed; I put on the petticoat of modesty, because love of reading shouldn’t carry one so far as to go about naked, and I ran to the door and opened it; but I hadn’t taken two steps on the landing when I felt someone seize my arm, and madame, who was watching at the door, cried:

"‘Aha! so this is the way you sleep, mesdemoiselles! But I propose to find out who it is that dares to leave the room in spite of my orders—to light her candle, I suppose.—I knew too much to make any answer. Madame called to Julie to come up with a light. I got away from her; and while she stood in the doorway to keep me from going back, I ran down to her apartment, put out the candles, and threw the matches out of the window. So madame couldn’t find out who it was that came out, and we passed the time feeling around for each other.—There! your hair’s all done, my friend."

"Thank God!—I remember that you made noise enough.—I must wait till they’re cold before I take them off.—Fifine! you’re a perfect devil! But no matter—I love you sincerely, and if I should ever be rich like Alfred——"

"Ah! then we should see some fine things, shouldn’t we?"

"Yes; you would see—In the first place, wealth wouldn’t make me any different; it’s so absurd to be proud and self-satisfied just because one has a few more yellow boys in one’s pocket! Does it increase one’s merit? I ask you that, Fifine?"

"It is certain that if you were a millionaire, your eyes wouldn’t be any larger."

"Bah! unkind girl! they are large enough to admire you.—Oh! stop that!"

"I have never heard you speak of this Alfred, whose party you are going to."

"He’s a boarding-school friend; he always used to play leap-frog with me. Since then, we have rather lost sight of each other; he is always in his carriage or in the saddle, and I go on foot."

"That’s better for the health."

"Well, with all his fortune Alfred is bored. Anyone can see that he doesn’t know what to do with himself. He is weary of pleasure; and then, he’s a rake, a libertine, a man incapable of true love."

"For a friend of yours, you give him a pretty character!"

"A friend of mine! oh! simply a boarding-school acquaintance, I tell you."

"Is he good-looking?"

"Yes, rather; that is to say, an ordinary face, but already worn and lined."

"Introduce him to me."

Robineau rose with an offended air and went to the mirror to remove his curl-papers.

"If I knew that he would make you happy, mademoiselle," he said, "I certainly would not hesitate! But I doubt if you would find in Alfred the profound and sincere affection which I feel for you."

"Dieu! my friend, how you do adore me to-night!"

"Because I’ve no carriage, you talk jestingly of abandoning me. But just let me get wealthy, and my only revenge will be to give you a magnificent country house."

"You must supply it with rabbits, understand, because I am very fond of rabbit stew. But meantime, while monsieur goes to his dance, I’m going to trim a cap."

"Downstairs?"

"No, upstairs."

"Is the shop closed already?"

"What, at nine o’clock? Don’t you follow the example of those evil tongues across the street, who say that the best part of our business is done when the shop is closed. Pretty shopkeepers they are, to talk about other people! The chief partner is bargaining for a place as box-opener at a theatre."

"There! How does my hair look?"

"Delicious, my friend! You’ll suffocate all rivals."

"Oh! all I care for is to be decent, presentable. You see, I make no pretensions."

"That is why you stand hours in front of your glass, practising smiles."

"For you alone, Fifine.—Ah! now where are my gloves?"

"I say, there’ll be a supper, no doubt, where you’re going? Bring me something."

"You expect me to put ices in my pocket, I suppose?"

"There’ll be other things besides ices; I want you to bring me some sweetmeats, or I’ll never put on curl-papers for you again."

"All right—we will see."

"Is monsieur going very far?"

"Rue du Helder."

"The milords’ quarter!—You mean to take a cab, no doubt?"

"I surely shan’t go on foot in this costume.—Let me see—it’s half past nine; I shall be at the Baron de Marcey’s at quarter to ten. That will do."

"Then it wasn’t worth while to make such a terrible fuss, my friend."

"There’s a cabstand almost in front of the house. I wonder if you would be kind enough to go down with me and call one?"

"That’s it; the only thing left for me to do will be to ride behind. But no matter; this is one of my good-natured days; forward!"

Robineau locked his door; Fifine went downstairs with him and called a cab, into which Robineau jumped after pressing the young milliner’s hand affectionately. She watched him go and called to him once more:

"Don’t forget to bring me something good!"

The cab halted in front of a handsome hôtel. There was a long line of private carriages waiting to enter the courtyard; one would have thought that they were taking their owners to the Bouffes, or to see the English actors. There is not so large an audience at the Français when they are playing Molière or Racine; but our actors have not made a special study of the death agony of a moribund; they do not exhibit to us all the dying convulsions of a man who is being murdered, nor make us hear all the hiccoughs of a princess who is starving to death; those pretty little episodes are very pleasant to witness, they excite the nerves of people who need such tableaux to arouse the slightest emotion. And yet there are some people who claim that it is more difficult to act well a scene from Tartufe or Le Misanthrope, than to imitate a scene from the Place de Grève. But let us allow every one to follow his or her taste, and let us be content to congratulate him who still enjoys a play that does not last forty years, and who is moved by a scene in which no one dies.

When he saw the throng of carriages and the brilliantly lighted salons, Robineau said to himself:

"This will be a very numerous, very fashionable and very well assorted affair!"

He at once alighted from his cab, and hurried toward the entrance, passing his hand over his curls and putting on his second glove. Then he went up to the first floor, reflecting thus:

"After all, I am as good as all these people—better perhaps. Even if they do have carriages—what difference does it make to me?"

Robineau said this to himself in order that he might not seem embarrassed and intimidated when he entered the salons; but it did not prevent his being red of face and stiff and awkward when he found himself in the midst of the guests, where he vainly sought Alfred for some time. At last his friend came to him, and, taking his arm, began by indulging in some jesting remarks concerning divers persons present. This gave Robineau time to recover himself; he resumed his self-assurance, his customary smile, and began to cast his eyes upon the ladies, thinking only of making conquests.

"By the way, your father, Monsieur le Baron de Marcey—I have not yet had the honor of paying my respects to him," said Robineau, as he gazed admiringly at some very pretty young ladies who had just entered the salon.

"My father has seen you before; must I present you to him again? It’s the same ceremony every time!"

"It’s a long time since he saw me, my dear fellow, and——"

"That makes no difference; you have one of those faces that no one ever forgets."

As he spoke, Alfred walked away to speak to some ladies, and Robineau murmured:

"I certainly have a face that—I wonder if he meant that for an epigram? that would be very becoming in him.—Ah! there is Monsieur de Marcey."

A man of some forty-eight years was passing Robineau at that moment; he was of tall stature and his carriage was noble and imposing; his strongly marked features were still very handsome, although they seemed to be already fatigued by too intense emotions rather than by years. He was a little bald in front, although his hair was still dark; lastly, his face was habitually serious and almost stern. But to those persons who could read his countenance more understandingly, the expression of his somewhat sombre glance was rather melancholy than severe. However, his black eyes grew softer, and a faint smile played about his lips whenever he looked at his son. Such was the Baron de Marcey.

"Monsieur de Marcey,—I have the honor—I am much flattered——"

The baron glanced at Robineau for an instant, then exclaimed:

"Ah! this is Monsieur Robineau, I believe?"

"Yes, monsieur, an intimate friend of your son, who invited me to come; and I took advantage of——"

"My son’s friends will always be mine, monsieur, and they confer a favor on me by coming to my house."

As he spoke, Monsieur de Marcey bowed to Robineau, and passed on to speak with other guests, while the government clerk puffed himself up and sauntered through the throng, saying to himself:

"Monsieur de Marcey is always extremely amiable to me; indeed I consider him more amiable than his son, because he hasn’t always that mocking air.—Ah! there’s the music; they are going to dance. I think I will dance, too; but with a pretty woman, for I can never keep in step with an ugly one,—it’s no use for me to try."

The orchestra had given the signal; one of Tolbecque’s lovely strains drew the dancers together from all sides, and charmed the ears of those who did not dance, but who, as they watched beauty and innocence chasser and balancer, listened with delight to airs selected from our best composers’ prettiest operas.

Robineau addressed himself too late to several comely young ladies who were already engaged; he was forced to take a partner who had naught in her favor save her youth and a very stylish costume. He heard somebody call her madame la comtesse, and that made him desirous to distinguish himself as her partner; but she seemed to pay very little heed to his airs and graces, and replied only by monosyllables to the complimentary remarks he addressed to her.

"She’s a prude!" Robineau muttered, after he had escorted the countess to her seat; and he proceeded to invite a very attractive young person to whom also he essayed to play the amiable; but she contented herself with smiling at what he said to her, and seemed wholly intent on the dance.

"She’s a fool!" thought Robineau, as he carried his homage elsewhere. But finding that he created no sensation, despite his energetic movements and the smiles he lavished on his partners, he left the ball-room.

"After all," he muttered, "among all these fine ladies there isn’t one who comes up to Fifine! And if Fifine had a tulle gown, and a wreath in her hair, and some of those great bracelets with antique cameos—ah! what a sensation she’d make!—I’ll take a look at the écarté table. I will carelessly bet a five-franc piece.—Ah! the deuce! there are ices; I’ll begin by seizing one on the wing."

Robineau took an ice, and, in order to eat in comfort, seated himself behind two gentlemen of mature years, who were talking together in a small salon between the ball-room and the card-room.

"How he has changed!" observed one of the two gentlemen, looking at Monsieur de Marcey, who happened to pass through the salon.

"Changed! whom do you mean?"

"De Marcey."

"Oh! do you think so?"

"If you had known De Marcey twenty-five years ago, as I did, my dear Dolmont——"

"Parbleu! that’s just it—twenty-five years ago; and it seems to you that it was only yesterday—and that he ought to appear the same to-day."

"No, no, I don’t say that.—Dear De Marcey! We made the Austerlitz campaign together."

"Oho! were you at Austerlitz?"

"Yes, indeed; I am proud to say that I was; and I have been in almost every battle that has been fought since. Now, I am resting."

Robineau took his eyes from his vanilla ice for an instant, to look at the speaker. He saw a man of fifty, whose frank and intelligent face bore more than one scar; his buttonhole was decorated with several orders, and Robineau said to himself:

"This gentleman has well earned his decorations—that is sure!"

"To be sure," rejoined the old soldier’s companion a moment later, "De Marcey is not old; he entered the service early in life, as you did; but so many things have happened since that it always seems as if centuries had passed over our heads."

"For my part, when I think of my campaigns, it seems as if it had all happened no longer ago than yesterday, for I fancy that I am still in the field!"

"He is like me," thought Robineau, "when I think of my first fancy. And yet it was ten years ago. She was a figurante at the Porte-Saint-Martin, and on the day of our first rendezvous we dined at the Vendanges de Bourgogne, Faubourg du Temple. It wasn’t a fashionable restaurant then as it is to-day, and there was no canal to cross to get there; but they served delicious sheep’s-trotters. It seems to me that I am there still. I was eighteen years old then. Ah me! one grows old without perceiving it!"

And Robineau heaved a sigh—which did not prevent his finishing his ice.

"When I say, Dolmont, that De Marcey seems changed to me, I refer to his temperament rather than to his physical aspect. If you had known him long ago—he was always in high spirits and a jovial companion; he used to laugh and joke with us. He was fond of the ladies—oh! he was a great lady’s man. But he was jealous of his mistresses, very jealous! I recall that on various occasions that tendency led him into quarrels; and indeed it was on account of it, I believe, that they married him at twenty-three to a young lady for whom he cared very little. His parents maintained that, with his jealous disposition, if he married for love he would be unhappy. And in fact his marriage began very auspiciously. I knew De Marcey’s first wife; she was a very attractive woman, and I believe that she would have made her husband very happy; unfortunately she died, a year after giving birth to a son. I learned that De Marcey married again after six years; but I was not in Paris then, and De Marcey had left the army. I never knew his second wife."

"He didn’t marry the second time in Paris, but somewhere in the neighborhood of Bordeaux. It seems that his wife’s family had an estate there, and the marriage took place on that property. Indeed, I think that he did not return to Paris with his wife until long after his second marriage."

"And what sort of person was his second wife?"

"Charming! One of those exquisite faces such as the painters succeed in producing occasionally, but which we see much less frequently in the world."

"The deuce!"

"But she had a sad, melancholy air; when she smiled, the smile seemed to conceal a secret grief. I never saw her dance, although she was very young, eighteen at most; but she seemed to shun the pleasures suited to her age, and to go into society solely to please her husband."

"And De Marcey was very fond of her?"

"Oh! he adored her; he seized every opportunity of giving her pleasure. He was untiring in his devotion to her."

"Did he have any children by her?"

"No; but the lovely Adèle—that was the second wife’s name—loved little Alfred dearly, and manifested all a mother’s affection for him. She died after three years; De Marcey’s grief was so violent that for a long time his life was in danger. At last, the sight of his son, meditation, lapse of time——"

"Yes, time! that is the all-powerful remedy. But for all that, I am no longer surprised that his humor is so changed from what it was! One may overcome the most profound sorrow, but it always leaves its traces. It is like the severe wounds, which heal, but of which one always carries the scars."

With that the old soldier rose, his companion did the same, leaving Robineau alone on his chair, which he at once quitted, saying to himself:

"It is very entertaining to listen to other people’s conversation, and it’s instructive, too; you seem to be paying no attention, but you listen; especially when people talk loud, for that means that they are not saying anything that they wish to conceal. Ah! I must listen to the conversation of some of the ladies; that will be even more amusing, because they always sprinkle their talk with wit; when I say always, I mean of course those who have wit.—Yonder are two ladies who seem to be engaged in a most interesting conversation, for they are talking with great animation. There’s a vacant chair beside them."

Robineau nonchalantly took his seat beside two pretty women, and turning his ear toward them as if without design, caught some fragments of their conversation.

"Yes, my dear love, I judged him rightly. I was wise, as you see, to distrust his protestations of love, his ardent oaths, his profound sighs! And yet you cannot conceive with what an air of sincerity he told me that he proposed to be virtuous and faithful henceforth, and to love no one but me! It is ghastly to lie like that!"

Robineau turned his head so that he could see the speaker’s face; and he saw a lovely brunette, whose vivacious and intelligent features expressed at that moment a sentiment of vexation which she tried to conceal beneath a forced smile.

"My dear Jenny, I believe that you are a little annoyed because you put Alfred’s love to the proof."

"Annoyed! on the contrary, I am delighted. I did not believe in it for an instant; his reputation with respect to women is too well established for——"

At that point she lowered her voice and Robineau could not hear the rest of her sentence; but he thought:

"They are talking about Alfred—this is delightful!—She is a person he has been making love to, no doubt. Gad! how amusing it is!"

The other lady, who also was young and pretty, replied after a moment:

"I am inclined to think that I should have more confidence in his friend, Monsieur Edouard Beaumont; he has a less frivolous, less heedless air than Alfred; and he is very good-looking, is Edouard; he has a very pretty figure."

"Mon Dieu! my dear love, I’ll wager that he is no better than other men. It is safer to distrust those cold, reserved manners, too. Nobody is worse than such men, when it comes to deceiving us poor women. With a scapegrace who makes no pretence of concealing what he is, one knows what to expect at all events."

"And that is why you have a weakness for Alfred, I suppose?"

"Oh! never! never! I laughed at his oaths of love. Perhaps it amused me a little to listen to him.—But, although he is agreeable and bright—as to loving him, oh! I promise you that I never dreamed of such a thing. Pray do not think that!"

"If you defend yourself so eagerly, Jenny, I shall end by believing that you adore him."

"Oh! upon my word, I——"

She lowered her voice again. Robineau tilted his chair a little in order to hear; but for several minutes the two friends spoke in such low tones that he could not catch a word. At last the charming Jenny observed aloud:

"You did well, very well. I am sure that it puzzles him tremendously to see us talking together, for he thought that we were at odds. Did he never talk to you about me?"

"Why, no; he talked about nobody but myself."

"Ah, yes! of course. I assure you, Clara, that I shall remain a widow; I shall never marry again!"

"Can anyone be sure of that, my dear? Remember that you are only twenty-two years old."

"An additional reason for not endangering the happiness of my life. Is not what I have known of marriage likely to make me avoid it? Monsieur de Gerville married me when I was eighteen, having never paid court to me; without any idea whether I liked him or not, he asked my parents for my hand. He was rich, so they gave me to him. However, Monsieur de Gerville was young and good-looking. I might have loved him if he had taken the trouble to try to win my love, if he had simply tried to make me think that he loved me. I was such a little idiot then! I believed whatever anyone chose. But no—I was his wife, and he would have considered that he disgraced himself by making love to me, by paying me any attention. He had two or three mistresses who deceived him; but that was much better than loving his wife, who did not deceive him. However, he is dead, and it is my duty to forget the suffering he caused me; but I confess that that taste of married life left me with a very poor opinion of men in general. I believe them to be, as a rule, selfish, inconstant, unjust to women: they must have everything, and we must do without everything; they are pleased to be unfaithful, but they demand constancy from us; they are good-humored so long as we are fortunate enough to please them, but as soon as they begin to sigh for another woman, they do not give us another thought; instead of trying to conceal their unfaithfulness by redoubling their attentions and consideration for us, they become sulky, capricious, bad-tempered; and if we are so unfortunate as to manifest any regret at the change in their treatment of us, they accuse us of being jealous and exacting!"

"O Jenny! Jenny!"

"You will find out, my dear Clara, that it is all true. In fact, what happy couples can you mention? Only those where the wives close their eyes to their husbands’ infidelities. Oh! when we let them do whatever they choose, go in and out and run after other women, without ever calling them to account for their actions, then we are what they call good wives, and they deign to offer us an arm once a month."

"I see that Alfred’s inconstancy has soured you!"

"What do I care for Monsieur Alfred’s inconstancy? I tell you again, I listened to him only for the fun of it, and I never took his declarations of love seriously. However, I am very glad that I know—that I conceived the idea of——"

Here they lowered their voices once more; and as they had reached a very interesting point, and as Robineau was most desirous to learn what the idea was that had occurred to Madame de Gerville, he tilted his chair a little more in the hope of hearing. But the weight of his body overturned it, and before he could recover himself, he rolled at the feet of the two friends.

As they had paid no attention to their neighbor, they were not a little surprised when that gentleman fell almost on their laps. But Robineau rose hastily, stammered an apology and walked away, muttering:

"They polish their floors a great deal too much! It’s almost too slippery to stand up! I don’t understand why all the dancers don’t fall on top of one another. To be sure, they walk instead of dancing.—Curse that chair! I was just going to learn the idea of that pretty brunette—Madame Jenny de Gerville. I will remember the name, and I’ll drive Alfred crazy. Ah! it’s very amusing!"

Robineau returned to the ball-room and looked about for other groups of people conversing. He heard laughter near at hand, and found that it came from two ladies who were not dancing; there happened to be a vacant chair behind them and Robineau took possession of it.

"These ladies are laughing," he said to himself; "I’ll wager that they are making fun of some other women among the company. I mustn’t miss this! I didn’t have time to look at them, but I will scrutinize them when they turn.—Attention!"

"Oh! what a ridiculous creature that man must be, and how I would have liked to see him dancing with you! You must point him out to me when you see him."

"Oh, yes! never fear; he is easily recognizable. I can’t imagine where Monsieur de Marcey found him!"

"Good!" thought Robineau; "they are making fun of someone—I was sure of it."

And he moved nearer to them, taking care not to tilt his chair.

"Just imagine, my dear love, a short, fat, heavy, awkward man, with a big nose, stupid little eyes, lips that he presses together when he talks, and hair curled so tight that he looks like a negro!"

"Ha! ha! ha!"

"And with it all, such a pretentious manner! He asked me to dance—they were just forming for the first contra-dance; I accepted, and during the dance he tried to play the amiable, but he had nothing to say except the most commonplace things, all so flat and wornout that it made me very sorry for him!—When he found that I made no reply to those entertaining remarks, he took the liberty to squeeze my hand while we were dancing!—Ha! ha! ha!"

At that point, the lady who was speaking turned, and Robineau recognized the countess with whom he had danced the first contra-dance. The blood rushed to his face. Meanwhile, the lady, who instantly recognized the gentleman of whom she was speaking, with difficulty restrained an inclination to laugh, and gently touched her friend’s knee. But before the latter had time to turn, Robineau was already far away. He was beside himself with rage, and glared furiously about, muttering:

"Well, upon my word! that woman must be a great joker! I don’t know whether it was I she was talking about, but in any event, I hope she may find many of my kind!—But she’s too ugly to have any attention.—To say that I squeezed her hand! that is false! These ugly women are forever slandering us men; it’s because they are furious at not finding any lovers."

Having lost his desire to listen to conversations, Robineau bent his steps toward the card-room, making such a horrible grimace that Alfred, meeting him beside one of the tables, stopped him and said:

"Mon Dieu! what a face you are making, my dear Robineau! Have you been having hard luck?"

"I have lost three hundred francs!"

"That’s nothing; you will win them back." And Alfred walked away, while Robineau said to himself:

"He takes things easily! That’s nothing, he says! If I had lost three hundred francs, I should never get over it! But I am very sure not to lose any such sum, as I have only twenty-one francs fifty. I must risk that. I will try to win; but they say that it isn’t very prudent to play écarté at these large parties. However, at Monsieur le Baron de Marcey’s there can’t be any but honest people. No matter; I am going to bet on the one who is winning—that’s the best thing to do.—Who is having the luck?" asked Robineau as he drew near the card-table.

Unluckily for him, the luck changed; in a very short time he lost his twenty-one francs. Thereupon, making every effort to conceal his ill-humor, he turned away from the table.

"Good-bye to the trip into the country and the dinner at the restaurant on Sunday!" he thought. "Fifine will have to dine at her aunt’s, and I will play the guitar. It was well worth while for me to put myself out, dress in my best clothes and hire a cab, to come to a grand party!—It is very amusing, isn’t it? Women who laugh at you; men who stare at you as if they would like to walk on you; gamblers who win your money without giving you time to see where you are! Fifine is right: one has much more fun at Madame Saqui’s or at the Funambules when they play Le Fantôme Armé.—Let us take a look at the buffet. If I can’t put ices in my pocket, I can put some oranges and cakes."

Robineau went to the refreshment room; there were no oranges left, but there was an abundance of cakes. He stuffed his pockets with them while the servants brought refreshments, and he was about to make for the stairway when Edouard appeared in front of him. The young author stopped.

"Good evening, Monsieur Robineau," he said; "I haven’t seen you before—there are so many people here!"

"True; and look you, between ourselves, I don’t consider these enormous crushes very amusing; I confess that I have had enough of it, and I am going away."

"Already? Why, it’s only two o’clock. Oh! you must stay; Alfred wants us to take supper in his apartment after the party, and talk nonsense."

"Oh! I didn’t know. That makes a difference, if we are to have supper. The devil! if I had known, I wouldn’t have eaten so much sweet stuff. But no matter—I will stay."

"Let us walk about and look for pretty partners."

"I will gladly walk about; but as to dancing, I am done."

Robineau slapped his pockets softly, to flatten them, and followed Edouard, saying to himself:

"I am not sorry to be seen talking with an author; I will talk theatre with him, and people will think that he and I are working together on a play.—I will bet that you prefer the play to an evening party, eh, Monsieur Edouard?"

"That depends; there are pleasant parties and very tiresome plays."

"Oh! of course; but I mean to say that it is very pleasant to be an author.—I must tell you of a plot—I say a plot, but I have a dozen in my desk!—Oh! I have some astonishingly good ones!"

"I believe it."

"Plots for grand operas, opéra-comiques, vaudevilles, melodramas. Oh! I do a little of everything; I have an inexhaustible imagination, and if I had time——"

"Yes, time is always what those people lack who produce nothing."

"That is so, isn’t it? But I will show them to you. What I should like more than anything would be to have free admission to the theatres.—Ah! to be able to go behind the scenes, to see the actresses at close quarters, and the ballet-dancers, who make pirouettes, so they say, as they bid you good-evening! What a lot of conquests one might make!"

"Not so many as you think; you get accustomed to the wings, as you do to the auditorium, and you talk with a Turk or a Polish girl without noticing their costumes."

"Of course; habit—I understand; but to produce a play, to superintend the rehearsals and the performance."

"It is delightful when one succeeds; but even so, what vexations have to be undergone before that point is reached! Rehearsals where people are never prompt, where they talk instead of studying their parts, which makes it necessary to rehearse forty times what they should have learned in fifteen; actors who want to make over their parts, managers who want to rewrite your plays, actresses who don’t like their costumes, claqueurs who want all your tickets, and last of all the public, that will have none of your play: such is often the result of six weeks of discomfort, annoyances and hard work!"

"He says all this to take away any inclination on my part to write plays," thought Robineau. "All authors are like that; they try to disgust beginners. I won’t show him my plots; he would steal my ideas, and then say they were his own.—You are rather inclined to look at the dark side of things now, Monsieur Edouard," he said aloud, "because you are still sore from your failure."

"Oh! I assure you that I have forgotten all about it."

"Bah! nonsense! For my part, if I should be hissed, I think that I should be in a horrible humor.—By the way, have you seen your little sempstress again? But I suppose that she is already replaced, is she not?"

"Faith, no! I am beginning to be tired of these bonnes fortunes, in which, as Larochefoucauld says, there is everything except love. I think that I should prefer a little love and less pleasure."

"That is like me, I am for sentiment, for what is called pure sentiment. I have adored all the women I ever knew, even my figurante at the Porte-Saint-Martin; and on their side, they have all treated me with peculiar favor; I am their spoiled child."

"You are very fortunate, Monsieur Robineau!—For my part, I would like to find—I don’t know just how to express it, but it seems to me that there should be a secret sympathy acting at the same time on two hearts that are made for each other."

"Yes, I understand you; that is what happened to me with my first inclination, whom I met at the Bal du Colisée. We fell while waltzing, both at the same time. I instantly discovered a secret sympathy therein."

Edouard allowed a faint smile to escape him, and drew near to a quadrille in which some very pretty women were performing.

"What do you think of that little blonde, Monsieur Robineau?"

"Why, nothing extraordinary; a good complexion, and youth; but she doesn’t turn her feet out enough."

"You are hard to suit! I think her very attractive; her eyes are lovely, her bearing full of grace. She does not seem to have made a careful study of dancing, but anyone can see that she enjoys it.—And what of the tall one, opposite?"

"She is not pretty; her nose is much too long, and there seems to be no end to her arms; her hair is badly arranged——"

"Well, I think that she has a very bright face, and it seems to me that, while she is not pretty, she must be attractive. I will wager that her conversation is very agreeable—And that stout brunette that’s dancing now?"

"She is a perfect bundle, and she tears about like one possessed."

"But see how light she is, despite her stoutness! What vivacity gleams in her eyes!"

"I say, Monsieur Edouard, you claim to be weary of bonnes fortunes, and yet you find all women to your liking; they all attract you!"

"Although I am weary of ephemeral liaisons, I did not say that I proposed to love no more; on the contrary, I am at present in search of an opportunity to fall in love in earnest."

"Well, well! so am I, messieurs," cried Alfred, who had stopped beside his two friends and had overheard Edouard’s last words. "I have a heart to place, and may the devil take me if I have known what to do with it for the last fortnight!—Here are plenty of good-looking women, however!"

"Faith! messieurs," said Robineau, throwing out his chest, "I protest that I contemplate all the ladies with a most indifferent eye. I am a philosopher, you see; besides, I have what I need, and it would be difficult for me to find anything better."

"Aha! Robineau, then you must show her to us. You must ask us to dine with her."

"Upon my word! do you mean to say that you think that she’s a woman for mixed parties? a woman to be taken where there are men?"

"Are you trying to make us think that she’s a duchess?"

"Why—look you—that might be."

"Ha! ha!—What on earth have you got in your pockets, Robineau? Are you wearing false hips to please your Dulcinea?"

Robineau blushed and put his hands over his pockets as he replied:

"It’s some papers that I forgot to take out of my coat."

"If you danced with such pockets as that, you must have produced a tremendous effect!—Ha! ha! it’s worse than Mère Gigogne!—Are these ministerial papers, too?"

Robineau turned away in a pet and threw himself on a sofa, heedless of the fact that he was crushing his cakes; and there he remained until the end of the ball, when Alfred came to him and said:

"We are going up to my rooms, Robineau; we are going to finish the night at the table, with a few faithful friends. Will you join us?"

"Yes, to be sure."

"Then make up your mind to leave your couch, to which you seem to be glued like a pasha."

Robineau followed Alfred. Young De Marcey’s apartment was above his father’s, and contained everything that luxury, refinement and variety could suggest. It was a retreat that any petite-maitresse might have envied.

Four young men, as heedless and reckless as the master of the place, soon appeared in response to their friend’s invitation, and with Edouard and Robineau completed the party.

"Messieurs," said Alfred, presenting Robineau to his young friends, "allow me to introduce an old school-mate, a very good fellow, albeit slightly irascible when you talk to him of his conquests or his employment. Do not pay any attention to the size of his pockets; he maintains that it makes him more graceful. He is a little out of temper now because he lost some money at écarté; but we will make him tipsy and he will be a delightful companion."

All the young men laughed, and Robineau followed their example, crying:

"That devilish Alfred! always joking! But, as for making me tipsy, I defy you to do it, messieurs. I have a hard head, I tell you; I have never been known to get drunk."