THE FIRE-GODS

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: The Fire-Gods

A Tale of the Congo

Author: Charles Gilson

Release Date: March 24, 2012 [EBook #39255]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE FIRE-GODS***

Produced by Al Haines.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I--THE EXPLORERS' CLUB

The Explorers' Club no longer exists. To-day, as a matter of fact, it is a tea-shop in Old Bond Street--a small building, wedged between two greater ones, a fashionable milliner's and a famous Art Establishment. Towards the end of the last century, in what is known as the mid-Victorian era, the Explorers' Club was in the heyday of its glory.

The number of its members was limited to two hundred and fifty-one. In the inner smoking-room, through the green baize doors, where guests were not admitted, both the conversation and the company were at once remarkable and unique. The walls were adorned with the trophies of the chase: heads of elk, markhor, ibex, haartebeest and waterbuck; great lions and snarling tigers; mouflon from Cyprus, and the white leopard of the Himalayas. If you looked into the room through the glass peep-hole in one of the green baize doors, you might have thought at first that you beheld a menagerie, where the fiercest and the rarest beasts in the world were imprisoned in a single cage. But, presently, your attention would have been attracted by the great, sun-burnt men, sprawling in the leather chairs, dressed in tweeds for the most part, and nearly every one with a blackened briar pipe between his lips.

In those days, Africa was the "Dark Continent"; the source of the Nile and the Great Lakes were undiscovered, of the Congo nothing was known. Nor was this geographical ignorance confined to a single continent: in every part of the world, vast tracts of country, great rivers and mountains were as yet unexplored. And the little that was known of these uttermost parts of the earth never passed the green baize doors of the inner smoking-room of the Explorers' Club.

There, in an atmosphere blue with smoke, where a great fire roared in winter to keep the chill of the London fog from the bones of those who, time and again, had been stricken with the fevers of the equatorial parts, a small group of men would sit and talk by the hour. There great projects were suggested, criticised and discussed. A man would rise from his seat, take down a map of some half-discovered country, and placing his finger upon a blank space, announce in tones of decision that that was the exact spot to which he intended to go. And if he went, perhaps, he would not come back.

At the time our story opens, Edward Harden was probably the most popular member of the Explorers' Club. He was still a comparatively young man; and though his reputation rested chiefly upon his fame as a big game shot, he had rendered no mean service to the cause of science, as the honours heaped upon him by the Royal Geographical Society and kindred institutions fully testified.

It was early in June, and the height of the London season, when this six foot six of explorer walked up St. James's Street on the right-hand side. Somehow he felt that he was out of it. He was not one of the fashionable crowd in the midst of which he found himself. For ten years he had been growing more and more unaccustomed to the life of cities. It was a strange thing, he could break his way through the tangled thicknesses of an equatorial forest, or wade knee-deep in a mangrove swamp, but he could never negotiate the passage of Piccadilly.

As he stood on the "island" in the middle of the street, opposite Burlington House, he attracted a considerable amount of attention. He was probably the tallest man at that moment between St. Paul's and the Albert Memorial. His brown moustache was several shades lighter than his skin, which had been burnt to the colour of tan. His long limbs, his sloping shoulders, and the slouch with which he walked, gave him an appearance of looseness and prodigious strength. Also he had a habit of walking with his fists closed, and his arms swinging like pendulums. He was quite unconscious of the fact that people turned and stared after him, or that he was an object of exceeding admiration to small boys, who speculated upon the result of a blow from his fist.

He had not gone far along Bond Street when he cannoned into a young man, who received a ponderous blow in the chest from Harden's swinging fist. The explorer could hardly have been expected to look where he was going, since at that moment he was passing a gunsmith's where the latest improvement of elephant gun was on view in the window.

"I beg your pardon!" he exclaimed in eager apology.

"It's nothing," said the other, and then added, with a note of surprise, "Uncle Ted, by all that's wonderful! I might have known it was you."

Edward Harden seldom expressed surprise. He just took the young gentleman by the arm and walked him along at the rate of about five miles an hour. "Come and have lunch," said he.

Now Max Harden, in addition to being the explorer's only nephew, was a medical student at one of the London hospitals. As a small boy, he had regarded his uncle as one of the greatest men in the universe--which, in a physical sense, he was.

A week before Max had come of age, which meant that he had acquired the modest inheritance of a thousand pounds a year. He had also secured a commission from the Royal Academy of Physicians to make sundry inquiries into the origin of certain obscure tropical diseases in the district of the Lower Congo. This was precisely the part of the world to which Edward Harden was about to depart. Max knew that quite well, and his idea was to travel with his uncle. He had been to the Explorers' Club, and had been told by the hall porter that Mr. Edward Harden was out, but that he would probably return for lunch. It was about two minutes later that he collided with his uncle outside the gunsmith's shop.

To lunch at the Explorers' Club was in itself an achievement. That day several well-known men were there: Du Cane, the lion hunter; Frankfort Williams, back from the Arctic, and George Cartwright, who had not yet accomplished his famous journey into Thibet. Upon the walls of the dining-room were full-length pictures of the great pioneers of exploration: Columbus, Franklin and Cook. It was not until after luncheon, when Max and his uncle were seated in the outer smoking-room--through the green baize doors, it will be remembered, it was forbidden for guests to enter--that Max broached the topic that was nearest to his heart.

"Uncle Ted," said he, "tell me about this expedition? As yet I know nothing."

"We're going up the Congo," answered Harden simply; "and it's natural enough that you should know nothing about it, since practically nothing is known. Our object is big game, but we hope to bring back some valuable geographical information. The mouth of the Congo was discovered by the Portuguese in the fifteenth century. Since then several trading-stations have sprung up on the river, but no one has penetrated inland. It is known that about five hundred miles from the mouth of the river, a tributary, called the Kasai, flows from the south. Of the upper valley of that river absolutely nothing is known, except that it consists of the most impenetrable forests and is inhabited by cannibal tribes. It is there we propose to go."

"Who goes with you?" asked Max.

"Crouch," said Harden; "Captain Crouch. The most remarkable man on the Coast. Nobody in England has ever heard of him; but on the West Coast, from Lagos to Loango, he is either hated like sin or worshipped like a heathen god. There's no man alive who understands natives as well as Crouch. He can get more work out of a pack of Kru-boys in a day than a shipping-agent or a trader can in a week."

"How do you account for it?" asked Max.

"Pluck," said Harden, "and perseverance. Also, from the day he was born, a special providence seems to have guarded him. For many years he was captain of a coasting-packet that worked from St. Louis to Spanish Guinea. He fell overboard once in the Bight of Biafra, and lost a foot."

"How did he do that?" asked Max, already vastly interested in the personality of Captain Crouch.

"Sharks," said Harden, as if it were an everyday occurrence. "They swim round Fernando Po like goldfish in a bowl. Would you believe it? Crouch knifed that fish in the water, though he'll wear a cork foot to his dying day. He was one of the first men to force his way up the Niger, and I happened to be at Old Calabar when he was brought in with a poisoned arrow-head in his eye. At that time the natives of the interior used to dip their weapons in snake's poison, and no one but Crouch could have lived. But he pulled through all right. He's one of those small, wiry men that can't be killed. He has got a case full of glass eyes now, of all the colours in the rainbow, and he plays Old Harry with the natives. If they don't do what he wants, I've seen him pull out a blue eye and put in a red one, which frightens the life out of them. Crouch isn't like any one else I've ever met. He has the most astonishing confidence in himself; he's practically fever-proof; he can talk about twenty West African dialects, and he's a better shot than I am. I believe the only person he cares for in the world is myself. I would never dream of undertaking this expedition without him."

"I suppose," said Max, a trifle nervously, "you wouldn't think of including a third member in your party?"

Edward Harden looked at his nephew sharply. "What do you mean?" he asked.

"I mean," said Max, "that I have undertaken to investigate certain tropical diseases, such as sleeping sickness and malarial typhoid, in the very districts to which you are going. I thought you might not object if I came with you. I didn't know I had Captain Crouch to deal with."

Edward Harden rose to his feet and knocked out his pipe in the grate.

"For myself," said he, "I should be pleased to have you with me. Are you ready to start at once? We hope to sail next week."

Max nodded.

"H'm," said the explorer, "I must ask Crouch. I think he's in the club."

He went to one of the green baize doors at the other end of the room, opened it, and looked in.

"Crouch," said he, "do you mind coming here a moment. There's something I want to ask you."

He then came back to his seat and filled another pipe. As he was engaged in lighting this, a green baize door swung back and there entered one of the most extraordinary men that it was ever the lot of the young medical student to behold.

As we have said, the Explorers' Club was in Bond Street, and Captain Crouch was dressed after the fashion of a pilot; that is to say, he wore a navy-blue suit with brass buttons and a red tie. He was a very small man, and exceedingly thin. There seemed nothing of him. His head was almost entirely bald. He wore a small, bristling moustache, cut short like a tooth-brush, and a tuft of hair beneath his nether lip. His eyebrows were exceedingly dark, and met on the bridge of his nose. His skin was the colour of parchment, and wrinkled and creased in all directions. He had a large hook nose, and a chin of excessive prominence. Though he appeared entirely bloodless, there was something about him that suggested extreme vital energy--the kind of vitality which may be observed in a rat. He was an aggressive-looking man. Though he walked with a pronounced limp, he was quick in all his movements. His mouth was closed fast upon a pipe in which he smoked a kind of black tobacco which is called Bull's Eye Shag, one whiff of which would fumigate a greenhouse, killing every insect therein from an aphis to a spider. He reeked of this as a soap-factory smells of fat. In no other club in London would its consumption have been allowed; but the Explorers were accustomed to greater hardships than even the smell of Bull's Eye Shag.

"Well, Ted," said Crouch, "what's this?"

One eye, big and staring, was directed out of the window; the other, small, black and piercing, turned inwards upon Max in the most appalling squint.

"This is my nephew," said Harden; "Max Harden--Captain Crouch, my greatest friend."

Max held out a hand, but Crouch appeared not to notice it. He turned to Edward.

"What's the matter with him?" he asked.

"He's suffering from a complaint which, I fancy, both you and I contracted in our younger days--a desire to investigate the Unknown. In a word, Crouch, he wants to come with us."

Crouch whipped round upon Max.

"You're too young for the Coast," said he. "You'll go out the moment you get there like a night-light."

"I'm ready to take my chance," said Max.

Crouch looked pleased at that, for his only eye twinkled and seemed to grow smaller.

Max was anxious to take advantage of the little ground he might have gained. "Also," he added, "I am a medical man--at least, I'm a medical student. I am making a special study of tropical diseases."

And no sooner were the words from his lips than he saw he had made a fatal mistake, for Captain Crouch brought down his fist so violently upon one of the little smokers' tables with which the room was scattered, that the three legs broke off, and the whole concern collapsed upon the floor.

"Do you think we want a medical adviser!" he roared. "Study till you're black in the face, till you're eighty years old, and you won't know a tenth of what I know. What's the use of all your science? I've lived on the Coast for thirty years, and I tell you this: there are only two things that matter where fever is concerned--pills and funk. Waiter, take that table away, and burn it."

It is probable that at this juncture Max's hopes had been dashed to earth had it not been for his uncle, who now put in a word.

"Tell you what, Crouch," said he, in the quiet voice which, for some reason or other, all big men possess; "the boy might be useful, after all. He's a good shot. He's made of the right stuff--I've known him since he was a baby. He's going out there anyhow, so he may as well come with us."

"Why, of course he may," said Crouch. "I'm sure we'll be delighted to have him."

Such a sudden change of front was one of the most remarkable characteristics of this extraordinary man. Often, in the breath of a single sentence, he would appear to change his mind. But this was not the case. He had a habit of thinking aloud, and of expressing his thoughts in the most vehement manner imaginable. Indeed, if his character can be summed up in any one word, it would be this one word "vehemence." He talked loudly, he gesticulated violently, he smashed the furniture, and invariably knocked his pipe out in such a frantic manner that he broke the stem. And yet Edward Harden---who knew him better than any one else in the world--always protested that he had never known Crouch to lose his temper. This was just the ordinary manner in which he lived, breathed and had his being.

"I'm sure," said Captain Crouch, "we will be delighted to take you with us. Ted, what are you going to do this afternoon?"

"I am going to get some exercise--a turn in the Park."

"I'll come with you," said Crouch.

So saying, he stumped off to fetch his cap which he had left in the inner room. No sooner was he gone than Max turned to his uncle.

"Uncle Ted," said he, "I can't thank you sufficiently."

The big man laid a hand upon the young one's shoulder.

"That's nothing," said he. "But I must tell you this: if you are coming with us to the Kasai, you must drop the 'uncle.' Your father was considerably older than I was--fifteen years. You had better call me by my Christian name--Edward. 'Ted's' a trifle too familiar."

By then they were joined by Crouch, who carried a large knotted stick in one hand, and in the other--a paper bag.

"What have you got there?" asked Harden, pointing to the bag.

"Sweets," said Crouch. "For the children in the Park."

And so it came about that they three left the Explorers' Club together, Max in the middle, with his gigantic uncle on one hand, and the little wizened sea-captain on the other.

They created no small amount of interest and amazement in Bond Street, but they were blissfully ignorant of the fact. The world of these men was not the world of the little parish of St. James's. One was little more than a boy, whose mind was filled with dreams; but the others were men who had seen the stars from places where no human being had ever beheld them before, who had been the first to set foot in unknown lands, who had broken into the heart of savagery and darkness. Theirs was a world of danger, hardship and adventure. They had less respect for the opinion of those who passed them by than for the wild beasts that prowl by night around an African encampment. After all, the world is made up of two kinds of men: those who think and those who act; and who can say which is the greater of the two?

CHAPTER II--ON THE KASAI

A mist lay upon the river like a cloud of steam. The sun was invisible, except for a bright concave dome, immediately overhead, which showed like the reflection of a furnace in the midst of the all-pervading greyness of the heavens. The heat was intense--the heat of the vapour-room of a Turkish bath. Myriads of insects droned upon the surface of the water.

The river had still a thousand miles to cover before it reached the ocean--the blazing, surf-beaten coast-line to the north of St. Paul de Loanda. Its turgid, coffee-coloured waters rushed northward through a land of mystery and darkness, lapping the banks amid black mangrove swamps and at the feet of gigantic trees whose branches were tangled in confusion.

In pools where the river widened, schools of hippopotami lay like great logs upon the surface, and here and there a crocodile basked upon a mud-bank, motionless by the hour, like some weird, bronze image that had not the power to move. In one place a two-horned rhinoceros burst through the jungle, and with a snort thrust its head above the current of the stream.

This was the Unknown. This was the World as it Had Been, before man was on the earth. These animals are the relics that bind us to the Past, to the cave-men and the old primordial days. There was a silence on the river that seemed somehow overpowering, rising superior to the ceaseless droning of the insects and the soft gurgling of the water, which formed little shifting eddies in the lee of fallen trees.

A long canoe shot through the water like some great, questing beast. Therein were twelve natives from Loango, all but naked as they came into the world. Their paddles flashed in the reflected light of the furnace overhead; for all that, the canoe came forward without noise except for the gentle rippling sound of the water under the bows. In the stern were seated two men side by side, and one of these was Edward Harden, and the other his nephew Max. In the body of the canoe was a great number of "loads": camp equipment, provisions, ammunition and cheap Manchester goods, such as are used by the traders to barter for ivory and rubber with the native chiefs. Each "load" was the maximum weight that could be carried by a porter, should the party find it necessary to leave the course of the river.

In the bows, perched like an eagle above his eyrie, was Captain Crouch. His solitary eye darted from bank to bank. In his thin nervous hands he held a rifle, ready on the instant to bring the butt into the hollow of his shoulder.

As the canoe rounded each bend of the river, the crocodiles glided from the mud-banks and the hippopotami sank silently under the stream. Here and there two nostrils remained upon the surface--small, round, black objects, only discernible by the ripples which they caused.

Suddenly a shot rang out, sharp as the crack of a whip. The report echoed, again and again, in the dark, inhospitable forest that extended on either bank. There was a rush of birds that rose upon the wing; the natives shipped their paddles, and, on the left bank of the river, the two-horned rhinoceros sat bolt upright on its hind-legs like a sow, with its fore-legs wide apart. Then, slowly, it rolled over and sank deep into the mud. By then Crouch had reloaded.

"What was it?" asked Harden.

"A rhino," said Crouch. "We were too far off for him to see us, and the wind was the right way."

A moment later the canoe drew into the bank a little distance from where the great beast lay. Harden and Crouch waded into the mire, knives in hand; and that rhino was skinned with an ease and rapidity which can only be accomplished by the practised hunter. The meat was cut into large slices, which were distributed as rations to the natives. Of the rest, only the head was retained, and this was put into a second canoe, which soon after came into sight.

After that they continued their journey up the wide, mysterious river. All day long the paddles were never still, the rippling sound continued at the bows. Crouch remained motionless as a statue, rifle in hand, ready to fire at a moment's notice. With his dark, overhanging brow, his hook nose, and his thin, straight lips, he bore a striking resemblance to some gaunt bird of prey.

A second shot sounded as suddenly and unexpectedly as the first, and a moment after Crouch was on his feet.

"A leopard!" he cried. "I hit him. He's wounded. Run her into the bank."

The canoe shot under a large tree, one branch of which overhung the water so low that they were able to seize it. Edward Harden was ashore in a moment, followed by his nephew. Crouch swung himself ashore by means of the overhanging bough. Harden's eyes were fixed upon the ground. It was a place where animals came to drink, for the soft mud had been trampled and churned by the feet of many beasts.

"There!" cried Harden. "Blood!"

Sure enough, upon the green leaf of some strange water plant there was a single drop of blood. Though the big game hunter had spoken in an excited manner, he had never raised his voice.

It was Crouch who took up the spoor, and followed it from leaf to leaf. Whenever he failed to pick it up, Harden put him right. Max was as a baby in such matters, and it was often that he failed to recognize the spoor, even when it was pointed out to him.

They had to break their way through undergrowth so thick that it was like a woodstack. The skin upon their hands and faces was scratched repeatedly by thorns. They were followed by a cloud of insects. They were unable to see the sky above them by reason of the branches of the trees, which, high above the undergrowth through which they passed, formed a vast barrier to the sunlight. And yet it was not dark. There was a kind of half-light which it is difficult to describe, and which seemed to emanate from nowhere. Nothing in particular, yet everything in general, appeared to be in the shade.

On a sudden Crouch stopped dead.

"He's not far from here," he said. "Look there!"

Max's eyes followed Crouch's finger. He saw a place where the long grass was all crushed and broken as if some animal had been lying down, and in two places there were pools of blood.

Crouch raised both arms. "Open out," said he. "Be ready to fire if he springs. He'll probably warn you with a growl."

This information was for the benefit of Max. To tell Edward Harden such things would be like giving minute instructions to a fish concerning the rudiments of swimming.

Max, obeying Crouch's orders, broke into the jungle on the left, whereas Edward moved to the right. Keeping abreast of one another, they moved forward for a distance of about two hundred yards. This time it was Harden who ordered the party to halt. They heard his quiet voice in the midst of the thickets: "Crouch, come here; I want you."

A moment later Max joined his two friends. He found them standing side by side: Edward, with eyes turned upward like one who listens, and Crouch with an ear to the ground. Harden, by placing a finger upon his lips, signed to his nephew to be silent. Max also strained his ears to catch the slight sound in the jungle which had aroused the suspicion of these experienced hunters.

After a while he heard a faint snap, followed by another, and then a third. Then there was a twanging sound, very soft, like the noise of a fiddle-string when thrummed by a finger. It was followed almost immediately by a shriek, as terrible and unearthly as anything that Max had ever heard. It was the dying scream of a wounded beast--one of the great tribe of cats.

Crouch got to his feet.

"Fans," said he. "What's more, they've got my leopard."

He made the remark in the same manner as a Londoner might point out a Putney 'bus; yet, at that time, the Fans were one of the most warlike of the cannibal tribes of Central Africa. They were reputed to be extremely hostile to Europeans, and that was about all that was known concerning them.

Edward Harden was fully as calm as his friend.

"We can't get back," said he. "It's either a palaver, or a fight."

"Come, then," said Crouch. "Let's see which it is."

At that he led the way, making better progress than before, since he no longer regarded the spoor of the wounded leopard.

Presently they came to a place where the jungle ceased abruptly. This was the edge of a swamp--a circular patch, about two hundred yards across, where nothing grew but a species of slender reed. Though Max had not known it, this was the very place for which the other two were looking. Backwoodsmen though they were, they had no desire to face a hostile tribe in jungle so dense that it would scarcely be possible to lift a rifle to the present.

The reeds grew in tufts capable of bearing the weight of a heavy man; but, in between, was a black, glutinous mud.

"If you fall into that," said Crouch, who still led the way, "you'll stick like glue, and you'll be eaten alive by leeches."

In the centre of the swamp the ground rose into a hillock, and here it was possible for them to stand side by side. They waited for several moments in absolute silence. And then a dark figure burst through the jungle, and a second later fell flat upon the ground.

"I was right," said Crouch. "That man was a Fan. We'll find out in a moment whether they mean to fight. I hope to goodness they don't find the canoes."

In the course of the next few minutes it became evident, even to Max, that they were surrounded. On all sides the branches and leaves of the undergrowth on the edge of the swamp were seen to move, and here and there the naked figure of a savage showed between the trees.

The Fans are still one of the dominant races of Central Africa. About the middle of the last century the tribe swept south-west from the equatorial regions, destroying the villages and massacring the people of the more peaceful tribes towards the coast. The Fans have been proved to possess higher intelligence than the majority of the Central African races. Despite their pugnacious character, and the practice of cannibalism which is almost universal among them, they have been described as being bright, active and energetic Africans, including magnificent specimens of the human race. At this time, however, little was known concerning them, and that little, for the most part, was confined to Captain Crouch, who, on a previous occasion, had penetrated into the Hinterland of the Gabun.

Edward Harden and his friends were not left long in doubt as to whether or not the Fans intended to be hostile, for presently a large party of men advanced upon them from all sides at once. For the most part these warriors were armed with great shields and long spears, though a few carried bows and arrows. The Fan spear is a thing by itself. The head is attached but lightly to the shaft, so that when the warrior plunges his weapon into his victims, the spear-head remains in the wound.

Captain Crouch handed his rifle to Edward, and then stepped forward across the marsh to meet these would-be enemies. He was fully alive to their danger. He knew that with their firearms they could keep the savages at bay for some time, but in the end their ammunition would run out. He thought there was still a chance that the matter might be settled in an amicable manner.

"Palaver," said he, speaking in the language of the Fans. "Friends. Trade-palaver Good."

The only answer he got was an arrow that shot past his ear, and disappeared in the mud He threw back his head and laughed.

"No good," he cried. "Trade-palaver friends."

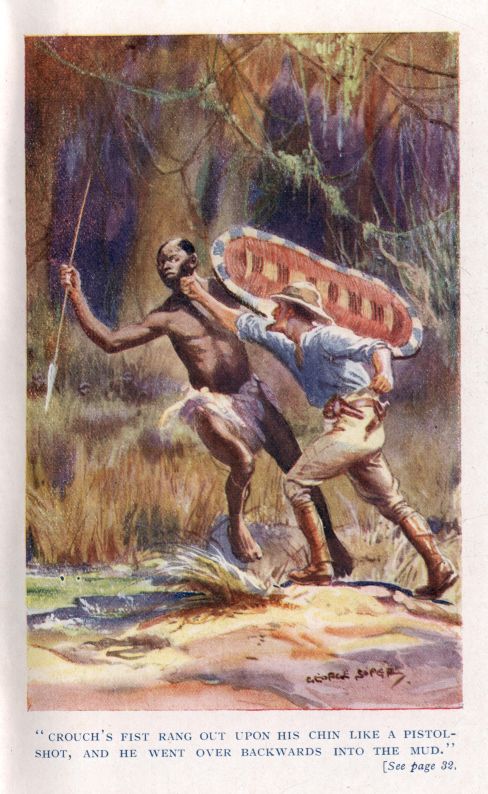

A tall, thin savage, about six feet in height, approached by leaps and bounds, springing like an antelope from one tuft of grass to another. His black face, with white, gleaming teeth, looked over the top of a large, oval shield. With a final spring, he landed on dry ground a few feet from where Crouch was standing. Then he raised his spear on high; but, before he had time to strike, Crouch's fist rang out upon his chin like a pistol-shot, and he went over backwards into the mud.

There was a strange, sucking noise as the marsh swallowed him to the chin. For some moments he floundered hopelessly, his two hands grasping in the air. He laid hold of tufts of grass, and pulled them up by the roots. Then Crouch bent down, gripped both his hands, and with a great effort dragged him on to terra firma.

His black skin was plastered with a blacker mud, and on almost every inch of his body, from his neck to his feet, a large water-leech was glued like an enormous slug. The man was already weak from loss of blood. Had he remained in the marsh a minute longer, there is no doubt he would have fainted. Crouch took a knife from his pocket, and, talking all the time, as a nursemaid talks to a naughty child, one by one he tore the leeches from the man's body, and threw them back into the marsh.

The others, who had drawn closer, remained at a safe distance. It seems they were undecided how to act, since this man was their leader, and they were accustomed to receive their orders from him. It is impossible to say what would have happened, had not Crouch taken charge of the situation. He asked the man where his village was, and the fellow pointed to the east.

"Yonder," said he; "in the hills."

"Lead on," said Crouch. "We're coming home with you, for a cup of tea and a talk."

For a moment the man was too stupefied to answer. He had never expected this kind of reception from an individual who could have walked under his outstretched arm. What surprised him most of all was Crouch's absolute self-confidence. The Negro and Bantu races are all alike in this: they are extraordinarily simple-minded and impressionable. The Fan chieftain looked at Crouch, and then dropped his eyes. When he lifted them, a broad grin had extended across his face.

"Good," said he. "My village. Palaver. You come."

Crouch turned and winked at Max, and then followed the chief towards the jungle.

CHAPTER III--THE WHITE WIZARD

When both parties were gathered together on the edge of the marsh, Max felt strangely uncomfortable. Both Crouch and Edward seemed thoroughly at home, and the former was talking to the chief as if he had found an old friend whom he had not seen for several years. Putting aside the strangeness of his surroundings, Max was not able to rid his mind of the thought that these men were cannibals. He looked at them in disgust. There was nothing in particular to distinguish them from the other races he had seen upon the coast, except, perhaps, they were of finer physique and had better foreheads. It was the idea which was revolting. In the country of the Fans there are no slaves, no prisoners, and no cemeteries; a fact which speaks for itself.

Crouch and the chief, whose name was M'Wané, led the way through the jungle. They came presently to the body of the wounded leopard, which lay with an arrow in its heart. It was the "twang" of the bowstring that Max had heard in the jungle. And now took place an incident that argued well for the future.

M'Wané protested that the leopard belonged to Crouch, since the Englishman had drawn first blood. This was the law of his tribe. Crouch, on the other hand, maintained that the law of his tribe was that the game was the property of the killer. The chief wanted the leopard-skin, and it required little persuasion to make him accept it, which he was clearly delighted to do.

Crouch skinned the leopard himself, and presented the skin to M'Wané. And then the whole party set forth again, and soon came to a track along which progress was easy.

It was approaching nightfall when they reached the extremity of the forest, and came upon a great range of hills which, standing clear of the mist that hung in the river valley, caught the full glory of the setting sun. Upon the upper slopes of the hills was a village of two rows of huts, and at each end of the streets thus formed was a guard-house, where a sentry stood on duty. M'Wané's hut was larger than the others, and it was into this that the Europeans were conducted. In the centre of the floor was a fire, and hanging from several places in the roof were long sticks with hooks on them, the hooks having been made by cutting off branching twigs. From these hooks depended the scant articles of the chief's wardrobe and several fetish charms.

For two hours Crouch and the chief talked, and it was during that conversation that there came to light the most extraordinary episode of which we have to tell. From that moment, and for many weeks afterwards, it was a mystery that they were wholly unable to solve. Both Crouch and Harden knew the savage nature too well to believe that M'Wané lied. Though his story was vague, and overshadowed by the superstitions that darken the minds of the fetish worshippers, there was no doubt that it was based upon fact. As the chief talked, Crouch translated to his friends.

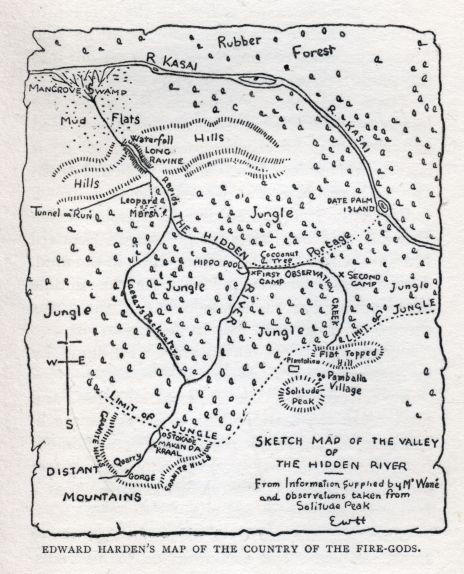

The chief first asked what they were doing on the Kasai, and Crouch answered that they were there for big game--for rhinoceros, buffalo and leopard. The chief answered that there was certainly much game on the Kasai, but there was more on the "Hidden River." That was the first time they ever heard the name.

Crouch asked why it was called the "Hidden River"; and M'Wané answered that it would be impossible for any one to find the mouth. On the southern bank of the Kasai, about two days up-stream, there was a large mangrove swamp, and it was beyond this that the "Hidden River" lay.

"Can you pass through the swamp in a canoe?" asked Crouch.

The chief shook his head, and said that a canoe could pass the mangrove swamp, but it could not penetrate far up the river, because of a great waterfall, where the water fell hundreds of feet between huge pillars of rock.

"One can carry a canoe," said Crouch.

"Perhaps," said M'Wané, as if in doubt. "But, of those that pass the cataract, none come back alive."

"Why?" asked Crouch.

"Because of the Fire-gods that haunt the river. The Fire-gods are feared from the seacoast to the Lakes."

Crouch pricked up his ears like a terrier that scents a rat. The little man sat cross-legged, with his hands upon his ankles; and as he plied the Fan chief with questions, he positively wriggled where he sat.

He found out that the "Fire-gods" were white men--a fact that astonished him exceedingly. He was told that they were not white men like himself and his friends, but wicked spirits who controlled the thunder and who could make the earth tremble for miles around. Even the Fans feared them, and for several months none of the tribes had ventured into the valley of the "Hidden River."

"They're men with rifles," said Harden. "These people have never seen a firearm in their lives."

At that he led M'Wané from the hut, and, followed by Max and Crouch, he walked a little distance from the village. There, in the moonlight, he picked up a stone from the ground, and set this upon a branch. From a distance of about twenty paces, with M'Wané at his side, he lifted his rifle to his shoulder, and struck the stone with a bullet, so that it fell upon the ground.

"There," said he, "that is what your Fire-gods do; they are armed with rifles--like this."

But M'Wané shook his head. He had heard of rifles. Tribes they had raided upon the coast had spoken of the white men that could slay at a distance. But the Fire-gods were greater still. Every evening, in the valley of the Hidden River, loud thunder rent the air. The birds had left the valley--even the snakes had gone. The Fire-gods were kings over Nature. Moreover, they were merciless. Hundreds of natives--men of the Pende tribe, the Pambala and the Bakutu--had gone into the valley; but no one had returned.

At that Crouch set off towards the hut without a word. The others, following, found him seated cross-legged at the fire, tugging at the tuft of hair which grew beneath his lip. For some minutes the little wizened sea-captain spoke aloud to himself.

"I'll find out who these people are," said he. "White men may have gone up the river to trade; but it's bad for business if you get a reputation for murder. I don't understand it at all. I've heard of a white race in the centre of the continent; maybe it's they. I hope it is. At any rate, we'll go and see."

For a few brief moments he lapsed into silence. Then he tapped M'Wané on the arm.

"Will you take us to the Hidden River?" he asked.

M'Wané sprang to his feet, violently shaking his head. He protested that he dared do nothing of the sort. They could not disbelieve him, for the man was actually trembling in his limbs.

Crouch turned to Harden.

"I've a mind to look into this," said he.

"I, too," said the other.

"He won't take us," said Max.

"I'll make him," said Crouch. "For the present, I'm going to sleep. The boys will stick to the canoes. We must get back to the river to-morrow afternoon. Good-night."

So saying, he curled himself up like a hedgehog, and, resting his head upon his folded arms, immediately fell asleep.

It was already three months since they had left Banana Point at the mouth of the Congo. They had journeyed to the foot of the rapids by steamboat, and thence had carried their canoes across several miles of country. They had enjoyed a good deal of mixed shooting in the lower valley, and then they had said good-bye to the few trading stations, or factories, which lay scattered at wide intervals upon the banks of the great river, and which were the last links that bound them to such civilization as the wilds of Africa could show. Max had already gained much experience of life in the wilds of tropical Africa. This was not the first time that he had found himself obliged to sleep upon the ground, without pillow or blankets, or that which was still more necessary--a mosquito-net.

When he opened his eyes it was daylight, and the first thing that he beheld was Captain Crouch, seated cross-legged at the fireside, with his pipe between his teeth. His one eye was fixed in the glowing embers. He appeared to be deep in thought, for his face was all screwed up, and he never moved. Thin wreaths of smoke came from the bowl of his pipe, and the hut reeked of his foul tobacco. Suddenly he snatched the pipe from his lips, and banged the bowl so viciously upon the heel of his boot that he broke it in twain. "I have it!" he cried. "I've got it!"

Max asked what was the matter.

"I've got an idea," said Crouch. "I'll make this fellow take us to the Hidden River, whether he wants to or not. They are frightened of these Fire-gods, are they! By Christopher, I'll make them more frightened of me, or my name was never Crouch!"

He got to his feet, and crossed the hut to M'Wané, who still lay asleep. He seized the chief by the shoulders and shook him violently, until the man sat up and rubbed his eyes.

"Your people," said he. "Big palaver. Now. Be quick."

M'Wané seemed to understand, for he got up and left the hut. Edward Harden was now awake.

The life that is lived by these Central African tribes finds a parallel in the ancient history of nearly all races that we know of. Government, for the most part, is in the hands of the headman of every village. The maintenance of law and order, the giving of wives, the exchange of possessions, is settled by "palaver," which amounts to a kind of meeting of the entire population, presided over by the chief. Near every village is a regular palaver-ground, usually in the shade of the largest tree in the neighbourhood.

It was here, on this early morning, that M'Wané summoned all the inhabitants of the village--men, women and children. They seated themselves upon the ground in a wide circle, in the midst of which was the trunk of a fallen tree. Upon this trunk the three Europeans seated themselves, Crouch in the middle, with his companions on either side.

When all was ready, M'Wané rose to his feet, and announced in stentorian tones that the little white man desired to speak to them, and that they must listen attentively to what he had to say. Whereupon Crouch got to his feet, and from that moment onward--in the parlance of the theatre--held the stage: the whole scene was his. He talked for nearly an hour, and during that time never an eye was shifted from his face, except when he called attention to the parrot.

He was wonderful to watch. He shouted, he gesticulated, he even danced. In face of his limited vocabulary, it is a wonder how he made himself understood; but he did. He was perfectly honest from the start. Perhaps his experience had taught him that it is best to be honest with savages, as it is with horses and dogs. He said that he had made his way up the Kasai in order to penetrate to the upper reaches of the Hidden River. He said that he had heard of the Fire-gods, and he was determined to find out who they were. For himself, he believed that the Fire-gods were masters of some kind of witchcraft. It would be madness to fight them with spears and bows and arrows. He believed, from what he had heard, that even his own rifle would be impotent. High on a tree-top was perched a parrot, that preened its feathers in the sunlight, and chattered to itself. Crouch pointed this parrot out to the bewildered natives, and then, lifting his rifle to his shoulder, fired, and the bird fell dead to the ground. That was the power he possessed, he told them: he could strike at a distance, and he seldom failed to kill. And yet he dared not approach the Fire-gods, because they were masters of witchcraft. But he also knew the secrets of magic, and his magic was greater and more potent than the magic of the Fire-gods. He could not be killed; he was immortal. He was prepared to prove it. Whereat, he re-loaded his rifle, and deliberately fired a bullet through his foot.

The crowd rushed in upon him from all sides, stricken in amazement. But Crouch waved them back, and stepping up to Edward, told the Englishman to shoot again. Harden lifted his rifle to his shoulder, and sent a bullet into the ankle of Crouch's cork foot. Thereupon, Crouch danced round the ring of natives, shouting wildly, springing into the air, proving to all who might behold that he was a thousand times alive.

They fell down upon their faces and worshipped him as a god. Without doubt he had spoken true: he was invulnerable, immortal, a witch-doctor of unheard-of powers.

But Crouch had not yet done. Before they had time to recover from their amazement, he had snatched out his glass eye, and thrust it into the hands of M'Wané himself, who dropped it like a living coal. They rushed to it, and looked at it, but dared not touch it. And when they looked up, Crouch had another eye in the socket--an eye that was flaming red.

A loud moan arose from every hand--a moan which gave expression to their mingled feelings of bewilderment, reverence and fear. From that moment Crouch was "the White Wizard," greater even than the Fire-gods, as the glory of the sun outstrips the moon.

"And now," cried Crouch, lifting his hands in the air, "will you, or will you not, guide me to the Hidden River where the Fire-gods live?"

M'Wané came forward and prostrated himself upon the ground.

"The White Wizard," said he, "has only to command."

CHAPTER V--THE STOCKADE

As the bullet cut into the water Crouch sprang upright in the canoe. His thin form trembled with eagerness. The man was like a cat, inasmuch as he was charged with electricity. Under his great pith helmet the few hairs which he possessed stood upright on his head. Edward Harden leaned forward and picked up his rifle, which he now held at the ready.

By reason of the fact that the river had suddenly widened into a kind of miniature lake, the current was not so swift. Hence, though M'Wané and his Fans ceased to paddle, the canoe shot onward by dint of the velocity at which they had been travelling. Every moment brought them nearer and nearer to the danger that lay ahead.

In order to relate what followed, it is necessary to describe the scene. We have said that the wild, impenetrable jungle had ceased abruptly, and they found themselves surrounded by granite hills, in the centre of which lay a plain of glaring sand. To their left, about a hundred paces from the edge of the river, was a circular stockade. A fence had been constructed of sharp-pointed stakes, each about eight feet in height. There was but a single entrance into this stockade--a narrow gate, not more than three feet across, which faced the river. Up-stream, to the south, the granite hills closed in from either bank, so that the river flowed through a gorge which at this distance seemed particularly precipitous and narrow. Midway between the stockade and the gorge was a kraal, or large native village, surrounded by a palisade. Within the palisade could be seen the roofs of several native huts, and at the entrance, seated cross-legged on the ground, was the white figure of an Arab who wore the turban and flowing robes by which his race is distinguished, from the deserts of Bokhara to the Gold Coast. Before the stockade, standing at the water's edge, was the figure of a European dressed in a white duck suit. He was a tall, thin man with a black, pointed beard, and a large sombrero hat. Between his lips was a cigarette, and in his hands he held a rifle, from the muzzle of which was issuing a thin trail of smoke.

As the canoe approached, this man grew vastly excited, and stepped into the river, until the water had risen to his knees. There, he again lifted his rifle to his shoulder.

"Put that down!" cried Crouch. "You're a dead man if you fire."

The man obeyed reluctantly, and at that moment a second European came running from the entrance of the stockade. He was a little man, of about the same build as Crouch, but very round in the back, and with a complexion so yellow that he might have been a Chinese.

The man with the beard seemed very agitated. He gesticulated wildly, and, holding his rifle in his left hand, pointed down-stream with his right. He was by no means easy to understand, since his pronunciation of English was faulty, and he never troubled to take his cigarette from between his lips.

"Get back!" he cried. "Go back again! You have no business here."

"Why not?" asked Crouch.

"Because this river is mine."

"By what right?"

"By right of conquest. I refuse to allow you to land."

The canoe was now only a few yards from the bank. The second man--the small man with the yellow face--turned and ran back into the stockade, evidently to fetch his rifle.

"I'm afraid," said Crouch, "with your permission or without, we intend to come ashore."

Again the butt of the man's rifle flew to his shoulder.

"Another yard," said he, "and I shoot you dead."

He closed an eye, and took careful aim. His sights were directed straight at Crouch's heart. At that range--even had he been the worst shot in the world--he could scarcely have missed.

Crouch was never seen to move. With his face screwed, and his great chin thrust forward, his only eye fixed in the midst of the black beard of the man who dared him to approach, he looked a very figure of defiance.

The crack of a rifle--a loud shout--and then a peal of laughter. Crouch had thrown back his head and was laughing as a school-boy does, with one hand thrust in a trousers pocket. Edward Harden, seated in the stern seat, with elbows upon his knees, held his rifle to his shoulder, and from the muzzle a little puff of smoke was rising in the air. It was the man with the black beard who had let out the shout, in anger and surprise. The cigarette had been cut away from between his lips, and Harden's bullet had struck the butt of his rifle, to send it flying from his hands into the water. He stood there, knee-deep in the river, passionate, foiled and disarmed. It was Edward Harden's quiet voice that now came to his ears.

"Hands up!" said he.

Slowly, with his black eyes ablaze, the man lifted his arms above his head. A moment later, Crouch had sprung ashore.

The little sea-captain hastened to the entrance of the stockade, and, as he reached it, the second man came running out, with a rifle in his hands. He was running so quickly that he was unable to check himself, and, almost before he knew it, his rifle had been taken from him. He pulled up with a jerk, and, turning, looked into the face of Captain Crouch.

"I must introduce myself," said the captain. "My name's Crouch. Maybe you've heard of me?"

The man nodded his head. It appears he had not yet sufficiently recovered from his surprise to be able to speak.

"By Christopher!" cried Crouch, on a sudden. "I know you! We've met before--five years ago in St. Paul de Loanda. You're a half-caste Portuguese, of the name of de Costa, who had a trade-station at the mouth of the Ogowe. So you remember me?"

The little yellow man puckered up his face and bowed.

"I think," said he, with an almost perfect English accent--"I think one's knowledge of the Coast would be very limited, if one had never heard of Captain Crouch."

Crouch placed his hand upon his heart and made a mimic bow.

"May I return the compliment?" said he. "I've heard men speak of de Costa from Sierra Leone to Walfish Bay, and never once have I heard anything said that was good."

At that the half-caste caught his under-lip in his teeth, and shot Crouch a glance in which was fear, mistrust and anger. The sea-captain did not appear to notice it, for he went on in the easiest manner in the world.

"And who's your friend?" he asked, indicating the tall man with the black beard, who was now approaching with Edward Harden and Max.

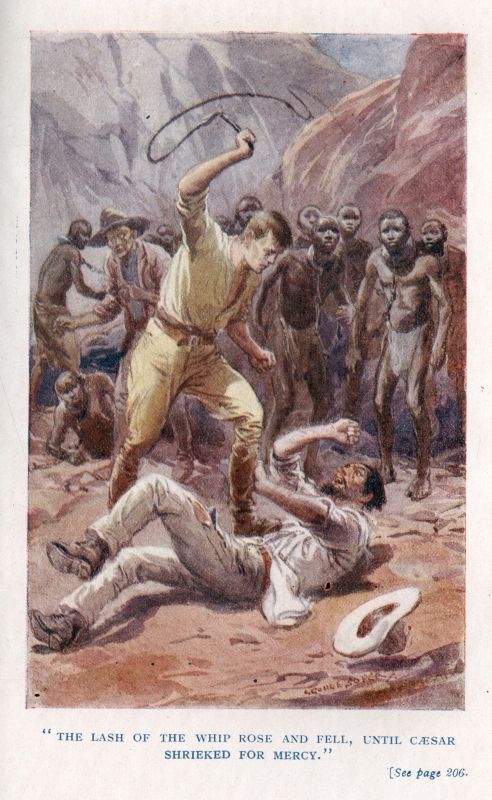

"My friend," said he, "is a countryman of mine, a Portuguese, who has assumed the name of Cæsar." The half-caste had evidently not forgotten the insult which Crouch had hurled in his teeth; for now his demeanour changed, and he laughed. "If Captain Crouch finds it necessary to meddle in our affairs," said he, "I think he will find his equal in Mister Cæsar."

Crouch paid no more attention to him than he would have done to a mosquito; and before the man had finished speaking, he had turned his back upon him, and held out a hand to the Portuguese.

"I trust," said he, "you've expressed your gratitude to Ted Harden, who, instead of taking your life, preferred to extinguish your cigarette."

"I have already done so," said Cæsar, with a smile. "I hope to explain matters later. The mistake was natural enough."

Crouch, with his one eye, looked this man through and through. He had been able to sum up the half-caste at a glance. Cæsar was a personality that could not be fathomed in an instant.

The man was not unhandsome. His figure, in spite of its extreme height and thinness, was exceedingly graceful. The hair of his moustache and beard, and as much as was visible beneath the broad-brimmed sombrero hat, was coal-black, and untouched with grey. His features were aquiline and large. He bore some slight resemblance to the well-known figure of Don Quixote, except that he was more robust. The most remarkable thing about him was his jet-black, piercing eyes. If there was ever such a thing as cruelty, it was there. When he smiled, as he did now, his face was even pleasant: there was a wealth of wrinkles round his eyes.

"It was a natural and unavoidable mistake," said he. "I have been established here for two years. You and your friends are, perhaps, sufficiently acquainted with the rivers to know that one must be always on one's guard."

Unlike de Costa, he spoke English with a strong accent, which it would be extremely difficult to reproduce. For all that, he had a good command of words.

"And now," he went on, "I must offer you such hospitality as I can. I notice the men in your canoes are Fans. I must confess I have never found the Fan a good worker. He is too independent. They are all prodigal sons."

"I like the Fan," said Edward.

"Each man to his taste," said Cæsar. "In the kraal yonder," he continued, pointing to the village, "I have about two hundred boys. For the most part, they belong to the Pambala tribe. As you may know, the Pambala are the sworn enemies of the Fans. You are welcome to stay with me as long as you like, but I must request that your Fans be ordered to remain within the stockade. Will you be so good as to tell them to disembark?"

"As you wish," said Edward.

At Crouch's request, Max went back to the canoe, and returned with M'Wané and the four Fans. Not until they had been joined by the natives did Cæsar lead the way into the stockade.

They found themselves in what, to all intents and purposes, was a fort. Outside the walls of the stockade was a ditch, and within was a banquette, or raised platform, from which it was possible for men to fire standing. In the centre of the enclosure were three or four huts--well-constructed buildings for the heart of Africa, and considerably higher than the ordinary native dwelling-place. Before the largest hut was a flag-staff, upon which a large yellow flag was unfurled in the slight breeze that came from the north.

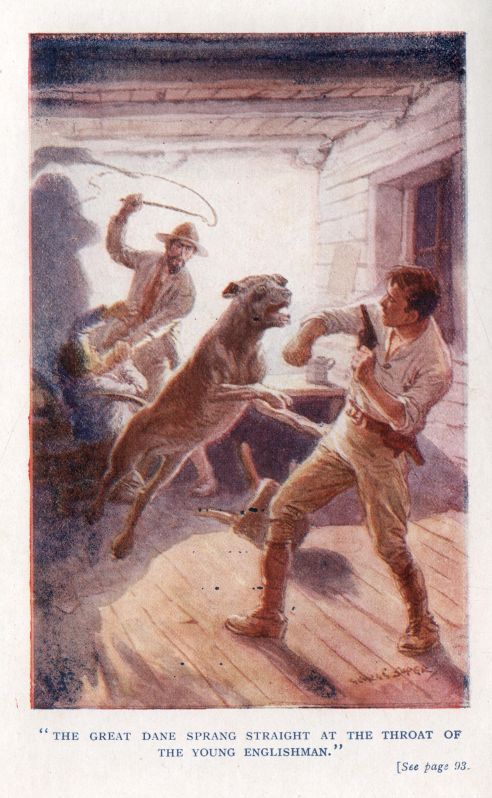

It was into this hut that they were conducted by the Portuguese. As the Englishman entered, a large dog, which had been lying upon the floor, got up and growled, but lay down again on a word from Cæsar. The interior of the hut consisted of a single room, furnished with a bed, a table and several chairs, all of which had been constructed of wood cut in the forest. As there were only four chairs, the half-caste, de Costa, seated himself on a large chest, with three heavy padlocks, which stood against the wall farthest from the door.

Cæsar crossed to a kind of sideboard, made of packing-cases, whence he produced glasses and a bottle of whisky. He then drew a jug of water from a large filter. These he placed upon the table. He requested his guests to smoke, and passed round his cigarette-case. His manner, and the ease with which he played the host, suggested a man of breeding. Both Edward Harden and his nephew accepted cigarettes, but Crouch filled his pipe, and presently the hut was reeking, like an ill-trimmed lamp, of his atrocious "Bull's Eye Shag."

"I owe you an apology," said Cæsar; "an apology and an explanation. You shall have both. But, in the first place, I would like to hear how it was that you came to discover this river?"

It was Edward Harden who answered.

"We were shooting big game on the Kasai," said he, "when we heard mention of the 'Hidden River.'"

"Who spoke of it?" said Cæsar. His dark eyes were seen to flash in the half-light in the hut.

"A party of Fans," said Edward, "with whom we came in contact. We persuaded them to carry our canoe across country. We embarked upon the river three days ago, and paddled up-stream until this afternoon, when we sighted your camp, and nearly came to blows. That's all."

Cæsar leaned forward, with his arms folded on the table, bringing his dark face to within a few inches of the cigarette which Edward held in his lips.

"Were you told anything," said he, in a slow, deliberate voice; "were you told anything--of us?"

Edward Harden, being a man of six foot several inches, was one who was guileless in his nature. He was about to say that the Fans had spoken of the "Fire-gods," when an extraordinary occurrence came to pass.

Crouch sprang to his feet with a yell, and placing one foot upon the seat of the chair upon which he had been sitting, pulled up his trousers to the knee. In his hand he held a knife. All sprang to their feet.

"What is it?" they demanded, in one and the same breath.

"A snake," said Crouch. "I'm bitten in the leg."

CHAPTER VI--CROUCH ON THE WAR-PATH

Both Cæsar and Edward hastened to the captain's side. Sure enough, upon the calf of his leg, were two small drops of blood, about a quarter of an inch apart, where the fangs of the reptile had entered.

Crouch looked up at Cæsar. His voice was perfectly calm.

"Where's the kitchen?" he demanded.

The tall Portuguese appeared suspicious.

"The kitchen is quite near at hand," said he. "Do you want to go there?"

"Yes," said Crouch. "Lead the way. There's no time to lose."

They passed out and entered a smaller hut, from which a column of smoke was rising through a hole in the roof. In the centre of the floor was a large charcoal brazier, at which a man was squatting in the characteristic attitude of the East. Crouch lifted his eyebrows in surprise when he saw that this man was an Arab.

"Tongs," said he in Arabic. "Lend me a pair of tongs."

The man, expressionless, produced the article in question.

Crouch took a piece of charcoal from the brazier, that was white-hot, and, without a moment's hesitation, he thrust this upon the place where the poison had entered his flesh. As he underwent that agony, his sallow face turned a trifle paler, his lips grew thinner, and his only eye more bright; but never a groan, or even a sigh, escaped him.

At last he threw the charcoal back into the fire.

"That's all right," said he. "It isn't a pleasant remedy, but it's sure." Then he turned to Cæsar. "I should like a little whisky," said he. "I feel a trifle faint."

He asked for Edward's arm to assist him on his way, and no sooner were they clear of the kitchen than he whispered in Harden's ear--

"There's nothing to worry about," said he. "I'm as right as rain. I was never bitten at all. But I had to stop you somehow, or you would have told that fellow what we heard of the Fire-gods. Mind, he must know nothing."

When they got back to the hut, Cæsar gave Crouch half a tumblerful of neat whisky, which the captain drained at a gulp. Needless to say, their efforts to find the snake proved fruitless. Then Crouch again complained of faintness, and asked permission to lie down upon the bed. No sooner was he there than he closed his eyes, and soon afterwards was sound asleep--if one was entitled to judge by his heavy breathing. Once or twice he snored.

But, already, we have seen enough of Captain Crouch to know that, in his case, it would not be wise to go by appearances. He was no more asleep than he had been throughout those long hours when he had kept watch in the bows of the canoe.

Cæsar motioned to Edward to be seated at the table, and Max took the chair which had been formerly occupied by Crouch. De Costa remained seated upon the chest.

"Let me see," said Cæsar; "of what were we speaking? Ah, yes, I remember. I was asking if the natives had made any mention of us."

"We asked many questions," said Harden, "but they knew little or nothing of the Hidden River. For some reason or other, they seemed to fear it."

Cæsar regarded Edward intently for a few seconds; and then, seeming satisfied, he shrugged his shoulders.

"Their minds are filled with superstitions," said he. "And now it remains for me to explain myself. I came to this valley two years ago. I had already journeyed some distance up the Congo, in search of ivory. I discovered that in the jungle in this valley elephants abound; moreover, these elephants are finer than any others I have ever seen in any part of Africa, even those of the East Coast, whose tusks are stored at Zanzibar. I made this place my headquarters. I regard the whole country as my own happy hunting-ground. I naturally resent all new-comers, especially Europeans. I look upon them as trespassers. Of course, I have no right to do so; I know that quite well. But you must understand that here, in the heart of Africa, the laws of civilized nations hardly apply. To all intents and purposes this country is my own. In the kraal yonder I have two hundred of the finest elephant hunters between the Zambesi and the Congo. I pay them well. I have already a great store of ivory. In another two years I hope to retire to Portugal, a wealthy man. That is all my story."

"How do you kill your elephants?" asked Edward. The hunting of big game was the foremost interest of his life.

Cæsar smiled.

"You will not approve of my methods," said he. "You are a sportsman; I am only a trader. I send my natives into the jungle, in the direction in which a herd of elephants has been located. These fellows creep on all-fours amid the undergrowth. They are as invisible as snakes. They are armed with long knives, with which they cut the tendons of the elephants' hind-legs, just below the knee. If an elephant tries to walk after that tendon has been severed, it falls to the ground and breaks its leg. The great beasts seem to know this, for they remain motionless as statues. When all the finest tuskers have been thus disposed of, I come with my rifle and shoot them, one after the other. Thus it is that I have collected a great store of tusks."

Edward Harden made a wry face.

"I have heard of that manner of hunting," said he. "It is much practised on the East Coast. I consider it barbarous and cruel."

Cæsar smiled again.

"I told you," said he, "you would not approve."

Harden swung round in his chair, with a gesture of disgust.

"I would like to see the ivory trade stopped," he cried, in a sudden flood of anger, very rare in a man naturally prone to be unexcitable and mild. "I regard the elephant as a noble animal--the noblest animal that lives. I myself have shot many, but the beast has always had a chance, though I will not deny the odds were always heavily on me. Still, when I find myself face to face with a rogue elephant, I know that my life is in danger. Now, there is no danger in your method, which is the method of the slaughter-house. At this rate, very soon there will be no elephants left in Africa."

"I'm afraid," said Cæsar, with a shrug of the shoulders, "we would never agree, because you're a sportsman and I'm a trader. In the meantime, I will do all I can to make you comfortable during your stay at Makanda."

"Is that the name of this place?" asked Max.

"Yes," said the Portuguese. "There was a native village when I came here--just a few scattered huts. The natives called the place Makanda, which, I believe, means a crater. The hills which surround us are evidently the walls of an extinct volcano. But, to come back to business, I can provide a hut for your Fan attendants, but they must be ordered not to leave the stockade. You have noticed, perhaps, that I employ a few Arabs. I am fond of Arabs myself; they are such excellent cooks. An Arab is usually on sentry at the gate of the stockade. That man will receive orders to shoot any one of the Fans who endeavours to pass the gate. These methods are rather arbitrary, I admit; but in the heart of Africa, what would you have? It is necessary to rule with an iron hand. Were I to be lax in discipline, my life would be in danger. Also, I must request you and your friends not to leave the stockade, unattended by either de Costa or myself. The truth is, there are several hostile tribes in the neighbourhood, and it is only with the greatest difficulty that I can succeed in maintaining peace."

"I'm sure," said Harden, "you will find us quite ready to do anything you wish. After all, the station is yours; and in this country a man makes his own laws."

"That is so," said Cæsar; and added, "I'm responsible to no one but myself."

This man had an easy way of talking and a plausible manner that would have deceived a more acute observer than Edward Harden. As he spoke he waved his hand, as if the whole matter were a trifle. He ran on in the same casual fashion, with an arm thrown carelessly over the back of his chair, sending the smoke of his cigarette in rings towards the ceiling.

"Most of us come to Africa to make money," said he; "and as the climate is unhealthy, the heat unbearable, and the inhabitants savages, we desire to make that money as quickly as possible, and then return to Europe. That is my intention. For myself, I keep tolerably well; but de Costa here is a kind of living ague. He is half consumed with malaria; he can't sleep by night, he lies awake with chattering teeth. Sometimes his temperature is so high that his pulse is racing. At other times he is so weak that he is unable to walk a hundred paces. He looks forward to the day when he shakes the dust of Africa from his shoes and returns to his native land, which--according to him--is Portugal, though, I believe, he was born in Jamaica."

Max looked at the half-caste, and thought that never before had he set eyes upon so despicable an object. He looked like some mongrel cur. He was quite unable to look the young Englishman in the face, but under Max's glance dropped his eyes to the floor.

"And now," said Cæsar, "there is a hut where I keep my provisions, which I will place at your disposal."

At that he went outside, followed by the two Hardens. De Costa remained in the hut. Crouch was still asleep.

Cæsar called the Arab from the kitchen, and, assisted by this man and the five Fans, they set to work to remove a number of boxes from the hut in which it was proposed that the three Englishmen should sleep. Blankets were spread upon the ground. The tall Portuguese was most solicitous that his guests should want for nothing. He brought candles, a large mosquito-net, and even soap.

Supper that evening was the best meal which Max had eaten since he left the sea-going ship at Banana Point on the Congo. The Portuguese was well provided with stores. He produced several kinds of vegetables, which, he said, he grew at a little distance from the stockade. He had also a great store of spirits, being under the entirely false impression that in tropical regions stimulants maintain both health and physical strength.

After supper, Cæsar and Captain Crouch, who had entirely recovered from his faintness, played écarté with an exceedingly dirty pack of cards. And a strange picture they made, these two men, the one so small and wizened, the other so tall and black, each coatless, with their shirt-sleeves rolled to the elbow, fingering their cards in the flickering light of a tallow candle stuck in the neck of a bottle. Crouch knew it then--and perhaps Cæsar knew it, too--that they were rivals to the death, in a greater game than was ever played with cards.

They went early to bed, thanking Cæsar for his kindness. Before he left the hut, Edward Harden apologized for his rudeness in finding fault with the trader's method of obtaining ivory.

"It was no business of mine," said he. "I apologize for what I said."

No sooner were the three Englishmen in their hut, than Crouch seized each of his friends by an arm, and drew them close together.

"Here's the greatest devilry you ever heard of!" he exclaimed.

"How?" said Edward. "What do you mean?"

"As yet," said Crouch, "I know nothing. I merely suspect. Mark my words, it'll not be safe to go to sleep. One of us must keep watch."

"What makes you suspicious?" asked Max. Throughout this conversation they talked in whispers. Crouch had intimated that they must not be overheard.

"A thousand things," said Crouch. "In the first place, I don't like the look of Arabs. There's an old saying on the Niger, 'Where there's an Arab, there's mischief.' Also, he's got something he doesn't wish us to see. That's why he won't let us outside the stockade. Besides, remember what the natives told us. The tribes the whole country round stand in mortal fear of this fellow, and they don't do that for nothing. The Fans are a brave race, and so are the Pambala. And do you remember, they told us that every evening there's thunder in the valley which shakes the earth? No, he's up to no good, and I shall make it my business to find out what his game is."

"Then you don't believe that he's an ivory trader?" asked Max.

"Not a word of it!" said Crouch. "Where's the ivory? He talks of this store of tusks, but where does he keep it? He says he's been here for two years. In two years, by the wholesale manner in which he has been killing elephants, according to his own account, he should have a pile of ivory ten feet high at least. And where is it? Not in a hut; not one of them is big enough. I suppose he'll ask us to believe that he keeps it somewhere outside the stockade."

"I never thought of that," said Harden, tugging the ends of his moustache. "I wonder what he's here for."

"So do I," said Crouch.

Soon after that, at Crouch's request, Harden and Max lay down upon their blankets, and were soon fast asleep. As for the captain, he also lay down, and for more than an hour breathed heavily, as if in sleep. Then, without a sound, he began to move forward on hands and knees across the floor of the hut.

When he reached the door he came into the moonlight, and had there been any one there to see, they would have noticed that he carried a revolver, and there was a knife between his teeth.

As quick as a lizard he glided into the shade beneath the walls of the hut. There he lay for some minutes, listening, with all his senses alert.

This man had much in common with the wild beasts of the forests. He was quick to hear, quick to see; it seemed as if he even had the power to scent danger, as the reed-buck or the buffalo.

His ears caught nothing but the varied sounds of wild, nocturnal life in the jungle. The stockade was not more than a hundred paces distant from the skirting of the forest. Somewhere near at hand a leopard growled, and a troop of monkeys, frightened out of their wits, could be heard scrambling through the branches of the trees. Farther away, a pair of lions were hunting; there is no sound more terrible and haunting than the quick, panting noise that is given by this great beast of prey as it follows upon the track of an antelope or deer. Then, far in the distance, there was a noise, so faint as to be hardly audible, like the beating of a drum. Crouch knew what it was. Indeed, in these matters there was little of which he was ignorant. It was a great gorilla, beating its stomach in passion in the darkness. And that is a sound before which every animal that lives in the jungle quails and creeps away into hiding; even the great pythons slide back into the depths of silent, woodland pools.

But it was not to the forest that Crouch's ear was turned. He was listening for a movement in the hut in which slept the Portuguese trader, who went by the name of Cæsar. After a while, seeming satisfied, he crawled on, in absolute silence, in the half-darkness, looking for all the world like some cruel four-footed beast that had come slinking from out of the jungle.

He reached the door of the hut, and crept stealthily in. Inside, he was not able to see. It was some little time before his eye grew accustomed to the darkness.

Then he was just able to discern the long figure of the Portuguese stretched upon his couch. Half-raising himself, he listened, with his ear not two inches from the man's mouth. Cæsar was breathing heavily. He was evidently fast asleep.

Still on hands and knees, as silently as ever, Crouch glided out of the hut.

Instead of returning by the way he had come, he turned in the opposite direction, and approached another hut. It was that which belonged to the half-caste, de Costa, whom he had met five years before in St. Paul de Loanda.

Once again he passed in at the door, silently, swiftly, with his knife still in his teeth.

This hut was even darker than the other, by reason of the fact that the door was smaller. Crouch sat up, and rubbed his eyes, and inwardly abused the universe in general because he was not able to see.

Suddenly there was a creaking noise, as if some one moved on the bed. Crouch was utterly silent. Then some one coughed. The cough was followed by a groan. De Costa sat up in bed. Crouch was just able to see him.

The little half-caste, resting his elbows on his knees, took his head between his hands, and rocked from side to side. He talked aloud in Portuguese. Crouch knew enough of that language to understand.

"Oh, my head!" he groaned. "My head! My head!" He was silent for no longer than a minute; then he went on: "Will I never be quit of this accursed country! The fever is in my bones, my blood, my brain!"

He turned over on his side, and, stretching out an arm, laid hold upon a match-box. They were wooden matches, and they rattled in the box.

Then he struck a light and lit a candle, which was glued by its own grease to a saucer. When he had done that he looked up, and down the barrel of Captain Crouch's revolver.

CHAPTER VII--THE WHITE MAN'S BURDEN

Before de Costa had time to cry out--which he had certainly intended to do--Crouch's hand had closed upon his mouth, and he was held in a grip of iron.

"Keep still!" said Crouch, in a quick whisper. "Struggle, and you die."

The man was terrified. He was racked by fever, nerve-shattered and weak. At the best he was a coward. But now he was in no state of health to offer resistance to any man; and in the candle-light Crouch, with his single eye and his great chin, looked too ferocious to describe.

For all that the little sea-captain's voice was quiet, and even soothing.

"You have nothing to fear," said he. "I don't intend to harm you. I have only one thing to say: if you cry out, or call for assistance, I'll not hesitate to shoot. On the other hand, if you lie quiet and silent, I promise, on my word of honour, that you have nothing whatsoever to fear. I merely wish to ask you a few questions. You need not answer them unless you wish to. Now, may I take my hand from your mouth?"

De Costa nodded his head, and Crouch drew away his hand. The half-caste lay quite still. It was obvious that he had been frightened out of his life, which had served to some extent to heighten the fever which so raged within him.

"Come," said Crouch; "I'll doctor you. Your nerves are all shaken. Have you any bromide?"

"Yes," said de Costa; "over there."

He pointed in the direction of a shelf upon the wall, which had been constructed of a piece of a packing-case. On this shelf was a multitude of bottles. Crouch examined these, and at last laid hands upon one containing a colourless fluid, like water, and handed it to the patient to drink. De Costa drained it at a gulp, and then sank back with a sigh of relief.

Crouch felt his pulse.

"You're weak," said he, "terribly weak. If you don't get out of this country soon you'll die. Do you know that?"

"I do," said de Costa; "I think of it every day."

"You don't wish to die?" said Crouch.

"I wish to live."

There was something pitiful in the way he said that. He almost whined. Here was a man who was paying the debt that the white man owes to Africa. In this great continent, which even to-day is half unknown, King Death rules from the Sahara to the veld. A thousand pestilences rage in the heart of the great steaming forests, that strike down their victims with promptitude, and which are merciless as they are swift. It seems as if a curse is on this country. It is as if before the advance of civilization a Power, greater by far than the combined resources of men, arises from out of the darkness of the jungle and the miasma of the mangrove swamp, and strikes down the white man, as a pole-axe fells an ox.

De Costa, though he was but half a European, was loaded with the white man's burden, with the heart of only a half-caste to see him through. Crouch, despite the roughness of his manner, attended at his bedside with the precision of a practised nurse. There was something even tender in the way he smoothed the man's pillow; and when he spoke, there was a wealth of sympathy in his voice.

"You are better now?" he asked.

"Yes," said de Costa; "I am better."

"Lie still and rest," said Crouch. "Perhaps you are glad enough to have some one to talk to you. I want you to listen to what I have to say."

Crouch seated himself at the end of the bed, and folded his thin, muscular hands upon his knee.

"I am not a doctor by profession," he began, "but, in the course of my life, I've had a good deal of experience of the various diseases which are met with in these parts of the world. I know enough to see that your whole constitution is so undermined that it is absolutely necessary for you to get out of the country. Now I want to ask you a question."

"What is it?" said de Costa. His voice was very weak.

"Which do you value most, life or wealth?"

The little half-caste smiled.

"I can see no good in wealth," said he, "when you're dead."

"That is true," said Crouch. "No one would dispute it--except yourself."

"But I admit it!" said de Costa.

"You admit it in words," said the other, "but you deny it in your life."

"I am too ill to understand. Please explain."

Crouch leaned forward and tapped the palm of his left hand with the forefinger of his right.

"You say," said he, "that you know that you'll die if you remain here. Yet you remain here in order to pile up a great fortune to take back with you to Jamaica or Portugal, wherever you intend to go. But you will take nothing back, because you will die. You are therefore courting death. I repeat your own words: what will be the use of all this wealth to you after you are dead?"

De Costa sat up in his bed.

"It's true!" he cried in a kind of groan.

"H'sh!" said Crouch. "Be quiet! Don't raise your voice."

De Costa rocked his head between his knees.