The Project Gutenberg EBook of Salem Witchcraft, Volumes I and II, by Charles Upham

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Salem Witchcraft, Volumes I and II

With an Account of Salem Village and a History of Opinions

on Witchcraft and Kindred Subjects

Author: Charles Upham

Release Date: February 24, 2006 [EBook #17845]

[Most recently updated: August 30, 2020]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SALEM WITCHCRAFT ***

Produced by Linda Cantoni and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

Charles W. Upham

FREDERICK UNGAR PUBLISHING CO.

New York

[Transcriber's Note: Originally published 1867]

Fourth Printing, 1969

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 59-10887

| Page | |

| Preface | vii to xiv |

| Map and Illustrations | xv to xvii |

| Index to the Map | xix to xxvii |

| General Index | xxix to xl |

| Introduction | 1 to 12 |

| Part First.—Salem Village | 13 to 322 |

| Part Second.—Witchcraft | 325 to 469 |

| Part Third.—Witchcraft at Salem Village | 1 to 444 |

| Supplement | 447 to 522 |

| Appendix | 525 to 553 |

THE TOWNSEND BISHOP HOUSE.—Vol. I., 70, 96; Vol. II., 294, 467.

THIS work was originally constructed, and in previous editions appeared, in the form of Lectures. The only vestiges of that form, in its present shape, are certain modes of expression. The language retains the character of an address by a speaker to his hearers; being more familiar, direct, and personal than is ordinarily employed in the relations of an author to a reader.

The former work was prepared under circumstances which prevented a thorough investigation of the subject. Leisure and freedom from professional duties have now enabled me to prosecute the researches necessary to do justice to it.

The "Lectures on Witchcraft," published in 1831, have long been out of print. Although frequently importuned to prepare a new edition, I was unwilling to issue again what I had discovered to be an insufficient presentation of the subject. In the mean time,[i.viii] it constantly became more and more apparent, that much injury was resulting from the want of a complete and correct view of a transaction so often referred to, and universally misunderstood.

The first volume of this work contains what seems to me necessary to prepare the reader for the second, in which the incidents and circumstances connected with the witchcraft prosecutions in 1692, at the village and in the town of Salem, are reduced to chronological order, and exhibited in detail.

As showing how far the beliefs of the understanding, the perceptions of the senses, and the delusions of the imagination, may be confounded, the subject belongs not only to theology and moral and political science, but to physiology, in its original and proper use, as embracing our whole nature; and the facts presented may help to conclusions relating to what is justly regarded as the great mystery of our being,—the connection between the body and the mind.

It is unnecessary to mention the various well-known works of authority and illustration, as they are referred to in the text. But I cannot refrain from bearing my grateful testimony to the value of the "Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society" and the "New-England Historical and Genealogical Register." The "Historical Collections" and the "Proceedings" of the Essex Institute have afforded me inestimable assistance. Such works as these are providing the materials[i.ix] that will secure to our country a history such as no other nation can have. Our first age will not be shrouded in darkness and consigned to fable, but, in all its details, brought within the realm of knowledge. Every person who desires to preserve the memory of his ancestors, and appreciate the elements of our institutions and civilization, ought to place these works, and others like them, on the shelves of his library, in an unbroken and continuing series. A debt of gratitude is due to the earnest, laborious, and disinterested students who are contributing the results of their explorations to the treasures of antiquarian and genealogical learning which accumulate in these publications.

A source of investigation, especially indispensable in the preparation of the present work, deserves to be particularly noticed. In 1647, the General Court of Massachusetts provided by law for the taking of testimony, in all cases, under certain regulations, in the form of depositions, to be preserved in perpetuam rei memoriam. The evidence of witnesses was prepared in writing, beforehand, to be used at the trials; they to be present at the time, to meet further inquiry, if living within ten miles, and not unavoidably prevented. In a capital case, the presence of the witness, as well as his written testimony, was absolutely required. These depositions were lodged in the files, and constitute the most valuable materials of history. In our[i.x] day, the statements of witnesses ordinarily live only in the memory of persons present at the trials, and are soon lost in oblivion. In cases attracting unusual interest, stenographers are employed to furnish them to the press. There were no newspaper reporters or "court calendars" in the early colonial times; but these depositions more than supply their place. Given in, as they were, in all sorts of cases,—of wills, contracts, boundaries and encroachments, assault and battery, slander, larceny, &c., they let us into the interior, the very inmost recesses, of life and society in all their forms. The extent to which, by the aid of William P. Upham, Esq., of Salem, I have drawn from this source is apparent at every page.

A word is necessary to be said relating to the originals of the documents that belong to the witchcraft proceedings. They were probably all deposited at the time in the clerk's office of Essex County. A considerable number of them were, from some cause, transferred to the State archives, and have been carefully preserved. Of the residue, a very large proportion have been abstracted from time to time by unauthorized hands, and many, it is feared, destroyed or otherwise lost. Two very valuable parcels have found their way into the libraries of the Massachusetts Historical Society and the Essex Institute, where they are faithfully secured. A few others have come to light among papers in the possession of individuals. It is to be[i.xi] hoped, that, if any more should be found, they will be lodged in some public institution; so that, if thought best, they may all be collected, arranged, and placed beyond wear, tear, and loss, in the perpetual custody of type.

The papers remaining in the office of the clerk of this county were transcribed into a volume a few years since; the copyist supplying, conjecturally, headings to the several documents. Although he executed his work in an elegant manner, and succeeded in giving correctly many documents hard to be deciphered, such errors, owing to the condition of the papers, occurred in arranging them, transcribing their contents, and framing their headings, that I have had to resort to the originals throughout.

As the object of this work is to give to the reader of the present day an intelligible view of a transaction of the past, and not to illustrate any thing else than the said transaction, no attempt has been made to preserve the orthography of that period. Most of the original papers were written without any expectation that they would ever be submitted to inspection in print; many of them by plain country people, without skill in the structure of sentences, or regard to spelling; which, in truth, was then quite unsettled. It is no uncommon thing to find the same word spelled differently in the same document. It is very questionable whether it is expedient or just to perpetuate[i.xii] blemishes, often the result of haste or carelessness, arising from mere inadvertence. In some instances, where the interest of the passage seemed to require it, the antique style is preserved. In no case is a word changed or the structure altered; but the now received spelling is generally adopted, and the punctuation made to express the original sense.

It is indeed necessary, in what claims to be an exact reprint of an old work, to imitate its orthography precisely, even at the expense of difficulty in apprehending at once the meaning, and of perpetuating errors of carelessness and ignorance. Such modern reproductions are valuable, and have an interest of their own. They deserve the favor of all who desire to examine critically, and in the most authentic form, publications of which the original copies are rare, and the earliest editions exhausted. The enlightened and enterprising publishers who are thus providing facsimiles of old books and important documents of past ages ought to be encouraged and rewarded by a generous public. But the present work does not belong to that class, or make any pretensions of that kind.

My thanks are especially due to the Hon. Asahel Huntington, clerk of the courts in Essex County, for his kindness in facilitating the use of the materials in his office; to the Hon. Oliver Warner, secretary of the Commonwealth, and the officers of his department; and to Stephen N. Gifford, Esq., clerk of the Senate.[i.xiii]

David Pulsifer, Esq., in the office of the Secretary of State, is well known for his pre-eminent skill and experience in mastering the chirography of the primitive colonial times, and elucidating its peculiarities. He has been unwearied in his labors, and most earnest in his efforts, to serve me.

Mr. Samuel G. Drake, who has so largely illustrated our history and explored its sources, has, by spontaneous and considerate acts of courtesy rendered me important help. Similar expressions of friendly interest by Mr. William B. Towne, of Brookline, Mass.; Hon. J. Hammond Trumbull, of Hartford, Conn.; and George H. Moore, Esq., of New-York City,—are gratefully acknowledged.

Samuel P. Fowler, Esq., of Danvers, generously placed at my disposal his valuable stores of knowledge relating to the subject. The officers in charge of the original papers, in the Historical Society and the Essex Institute, have allowed me to examine and use them.

I cordially express my acknowledgments to the Hon. Benjamin F. Browne, of Salem, who, retired from public life and the cares of business, is giving the leisure of his venerable years to the collection, preservation, and liberal contribution of an unequalled amount of knowledge respecting our local antiquities.

Charles W. Palfray, Esq., while attending the General Court as a Representative of Salem, in 1866,[i.xiv] gave me the great benefit of his explorations among the records and papers in the State House.

Mr. Moses Prince, of Danvers Centre, is an embodiment of the history, genealogy, and traditions of that locality, and has taken an active and zealous interest in the preparation of this work. Andrew Nichols, Esq., of Danvers, and the family of the late Colonel Perley Putnam, of Salem, also rendered me much aid.

I am indebted to Charles Davis, Esq., of Beverly, for the use of the record-book of the church, composed of "the brethren and sisters belonging to Bass River," gathered Sept. 20, 1667, now the First Church of Beverly; and to James Hill, Esq., town-clerk of that place, for access to the records in his charge.

To Gilbert Tapley, Esq., chairman of the committee of the parish, and Augustus Mudge, Esq., its clerk, and to the Rev. Mr. Rice, pastor of the church, at Danvers Centre, I cannot adequately express my obligations. Without the free use of the original parish and church record-books with which they intrusted me, and having them constantly at hand, I could not have begun adequately to tell the story of Salem Village or the Witchcraft Delusion.

C.W.U.

The map, based upon various local maps and the Coast-Survey chart, is the result of much personal exploration and perambulation of the ground. It may claim to be a very exact representation of many of the original grants and farms. The locality of the houses, mills, and bridges, in 1692, is given in some cases precisely, and in all with near approximation. The task has been a difficult one. An original plot of Governor Endicott's Ipswich River grant, No. III., is in the State House, and one of the Swinnerton grant, No. XIX., in the Salem town-books. Neither of them, however, affords elements by which to establish its exact location. A plot of the Townsend Bishop grant, No. XX., as its boundaries were finally determined, is in the State House, and another of the same in the court-files of the county. This gives one fixed and known point, Hadlock's Bridge, from which, following the lines by points of compass and distances, as indicated on the plot and described in the Colonial Records, all the sides of the grant are laid out with accuracy, and its place on the map determined with absolute certainty. A very perfect and scientifically executed plan of a part of the boundary between Salem and Reading in[i.xvi] 1666 is in the State House; of which an exact tracing was kindly furnished by Mr. H.J. Coolidge, of the Secretary of State's office. It gives two of the sides of the Governor Bellingham grant, No. IV., in such a manner as to afford the means of projecting it with entire certainty, and fixing its locality. There are no other plots of original or early grants or farms on this territory; but, starting from the Bishop and Bellingham grants thus laid out in their respective places, by a collation of deeds of conveyance and partition on record, with the aid of portions of the primitive stone-walls still remaining, and measurements resting on permanent objects, the entire region has been reduced to a demarkation comprehending the whole area. The locations of then-existing roads have been obtained from the returns of laying-out committees, and other evidence in the records and files. The construction of the map, in all its details, is the result of the researches and labors of W.P. Upham.

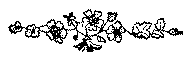

The death-warrant is a photograph by E.R. Perkins, of Salem. The original, among the papers on file in the office of the clerk of the courts of Essex County, having always been regarded as a great curiosity, has been subjected to constant handling, and become much obscured by dilapidation. The letters, and in some instances entire words, at the end of the lines, are worn off. To preserve it, if possible, from further injury, it has been pasted on cloth. Owing to this circumstance, and the yellowish hue to which the paper has faded, it does not take favorably by photograph; but the exactness of imitation, which can only thus be obtained with absolute certainty, is more important than any other consideration. Only so much as contains the body of the warrant, the sheriff's return, and the seal, are given.[i.xvii] The tattered margins are avoided, as they reveal the cloth, and impair the antique aspect of the document. The original is slowly disintegrating and wasting away, notwithstanding the efforts to preserve it; and its appearance, as seen to-day, can only be perpetuated in photograph. The warrant is reduced about one-third, and the return one-half.

The Townsend Bishop house and the outlines of Witch Hill are from sketches by O.W.H. Upham. The English house is from a drawing made on the spot by J.R. Penniman of Boston, in 1822, a few years before its demolition, for the use of which I am indebted to James Kimball, Esq., of Salem. The view of Salem Village and of the Jacobs' house are reduced, by O.W.H. Upham, from photographs by E.R. Perkins.

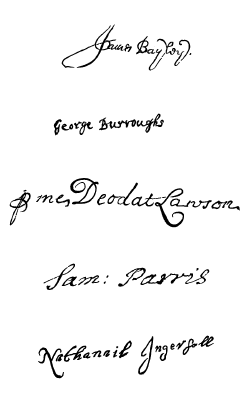

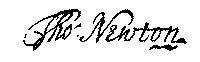

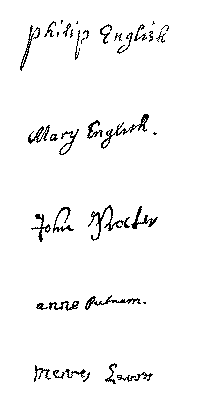

The map and other engravings, including the autographs, were all delineated by O.W.H. Upham.

[Transcriber's Note: The map was missing from the volume used to prepare this e-text. The map image below was reproduced from a scan at the University of Virginia's Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project, http://etext.virginia.edu/salem/witchcraft/maps.]

Map of Salem Village.

1692.

[The Map shows all the houses standing in 1692 within the bounds of Salem Village; some others in the vicinity are also given. The houses are numbered on the Map with Arabic numerals, 1, 2, 3, &c., beginning at the top, and proceeding from left to right. In the following list, against each number, is given the name of the occupant in 1692, and, in some cases, that of the recent occupant or owner of the locality is added in parenthesis.]

| s. | The same house believed to be still standing. |

| s.m. | The same house standing within the memory of persons now living. |

| t.r. | Traces of the house remain. |

| c. | The site given is conjectural. |

1. John Willard. c.

2. Isaac Easty.

3. Francis Peabody. c.

4. Joseph Porter. (John Bradstreet.)

5. William Hobbs. t.r.

6. John Robinson.

7. William Nichols. t.r.

8. Bray Wilkins. c.

9. Aaron Way. (A. Batchelder.)

10. Thomas Bailey.

11. Thomas Fuller, Sr. (Abijah Fuller.)

12. William Way.

13. Francis Elliot. c.

14. Jonathan Knight. c.

15. Thomas Cave. (Jonathan Berry.)

16. Philip Knight. (J.D. Andrews.)

17. Isaac Burton.

18. John Nichols, Jr. (Jonathan Perry and Aaron Jenkins.) s.

19. Humphrey Case. t.r.

20. Thomas Fuller, Jr. (J.A. Esty.) s.

21. Jacob Fuller.

22. Benjamin Fuller.

23. Deacon Edward Putnam. s.m.

24. Sergeant Thomas Putnam. (Moses Perkins.) s.

25. Peter Prescot. (Daniel Towne.)

26. Ezekiel Cheever. (Chas. P. Preston.) s.m.

27. Eleazer Putnam. (John Preston.) s.m.

28. Henry Kenny.

29. John Martin. (Edward Wyatt.)

30. John Dale. (Philip H. Wentworth.)

31. Joseph Prince. (Philip H. Wentworth.)

32. Joseph Putnam. (S. Clark.) s.

33. John Putnam 3d.

34. Benjamin Putnam.

35. Daniel Andrew. (Joel Wilkins.)[i.xx]

36. John Leach, Jr. c.

37. John Putnam, Jr. (Charles Peabody.)

38. Joshua Rea. (Francis Dodge.) s.

39. Mary, wid. of Thos. Putnam. (William R. Putnam.) s.

[Birthplace of Gen. Israel Putnam. Gen. Putnam also lived in a house, the cellar and well of which are still visible, about one hundred rods north of this, and just west of the present dwelling of Andrew Nichols.]

40. Alexander Osburn and James Prince. (Stephen Driver.) s.

41. Jonathan Putnam. (Nath. Boardman.) s.

42. George Jacobs, Jr.

43. Peter Cloyse. t.r.

44. William Small. s.m.

45. John Darling. (George Peabody.) s.m.

46. James Putnam. (Wm. A. Lander.) s.m.

47. Capt. John Putnam. (Wm. A. Lander.)

48. Daniel Rea. (Augustus Fowler.) s.

49. Henry Brown.

50. John Hutchinson. (George Peabody.) t.r.

51. Joseph Whipple. s.m.

52. Benjamin Porter. (Joseph S. Cabot.)

53. Joseph Herrick. (R.P. Waters.)

54. John Phelps. c.

55. George Flint. c.

56. Ruth Sibley. s.m.

57. John Buxton.

58. William Allin.

59. Samuel Brabrook. c.

60. James Smith.

61. Samuel Sibley. t.r.

62. Rev. James Bayley. (Benjamin Hutchinson.)

63. John Shepherd. (Rev. M.P. Braman.)

64. John Flint.

65. John Rea. s.m.

66. Joshua Rea. (Adam Nesmith.) s.m.

67. Jeremiah Watts.

68. Edward Bishop, the sawyer. (Josiah Trask.)

69. Edward Bishop, husbandman.

70. Capt. Thomas Rayment.

71. Joseph Hutchinson, Jr. (Job Hutchinson.)

72. William Buckley.

73. Joseph Houlton, Jr. t.r.

74. Thomas Haines. (Elijah Pope.) s.

75. John Houlton. (F.A. Wilkins.) s.

76. Joseph Houlton, Sr. (Isaac Demsey.)

77. Joseph Hutchinson, Sr. t.r.

78. John Hadlock. (Saml. P. Nourse.) s.m.

79. Nathaniel Putnam. (Judge Putnam.) t.r.

80. Israel Porter. s.m.

81. James Kettle.

82. Royal Side Schoolhouse.

83. Dr. William Griggs.

84. John Trask. (I. Trask.) s.

85. Cornelius Baker.

86. Exercise Conant. (Subsequently, Rev. John Chipman.)

87. Deacon Peter Woodberry. t.r.

88. John Rayment, Sr. (Col. J.W. Raymond.)

89. Joseph Swinnerton. (Nathl. Pope.)

90. Benjamin Hutchinson. s.m.

91. Job Swinnerton. (Amos Cross.)

92. Henry Houlton. (Artemas Wilson.)

93. Sarah, widow of Benjamin Houlton. (Judge Houlton.) s.

94. Samuel Rea.

95. Francis Nurse. (Orin Putnam.) s.

96. Samuel Nurse. (E.G. Hyde.) s.

97. John Tarbell. s.

98. Thomas Preston.

99. Jacob Barney.

100. Sergeant John Leach, Sr. (George Southwick.) s.m.

101. Capt. John Dodge, Jr. (Charles Davis.) t.r.

102. Henry Herrick. (Nathl. Porter.)

[This had been the homestead of his father, Henry Herrick.]

103. Lot Conant.

[This was the homestead of his father, Roger Conant.]

104. Benjamin Balch, Sr. (Azor Dodge.) s.

[This was the homestead of his father, John Balch.]

105. Thomas Gage. (Charles Davis.) s.

106. Families of Trask, Grover, Haskell, and Elliott.

107. Rev. John Hale.

108. Dorcas, widow of William Hoar.

109. William and Samuel Upton. c.

110. Abraham and John Smith. (J. Smith.) s.

[This had been the homestead of Robert Goodell.]

111. Isaac Goodell. (Perley Goodale.)

112. Abraham Walcot. (Jasper Pope.) s.m.

113. Zachariah Goodell. (Jasper Pope.)

114. Samuel Abbey.

115. John Walcot.

116. Jasper Swinnerton. s.m.

117. John Weldon. Captain Samuel Gardner's farm. (Asa Gardner.)

118. Gertrude, widow of Joseph Pope. (Rev. Willard Spaulding.) s.m.

119. Capt. Thomas Flint. s.

120. Joseph Flint. s.

121. Isaac Needham. c.

122. The widow Sheldon and her daughter Susannah.

123. Walter Phillips. (F. Peabody, Jr.)

124. Samuel Endicott. s.m.

125. Families of Creasy, King, Batchelder, and Howard.

126. John Green. (J. Green) s.

127. John Parker.

128. Giles Corey. t.r.

129. Henry Crosby.

130. Anthony Needham, Jr. (E. and J.S. Needham.)

131. Anthony Needham, Sr.

132. Nathaniel Felton. (Nathaniel Felton.) s.

133. James Houlton. (Thorndike Procter.)

134. John Felton.

135. Sarah Phillips.

136. Benjamin Scarlett. (District Schoolhouse No. 6.)

137. Benjamin Pope.

138. Robert Moulton. (T. Taylor.) c.

139. John Procter.

140. Daniel Epps. c.

141. Joseph Buxton. c.

142. George Jacobs, Sr. (Allen Jacobs.) s.

143. William Shaw.

144. Alice, widow of Michael Shaflin. (J. King.)

145. Families of Buffington, Stone, and Southwick.

146. William Osborne.

147. Families of Very, Gould, Follet, and Meacham.

+ Nathaniel Ingersoll.

¶ Rev. Samuel Parris. t.r.

□ Captain Jonathan Walcot. t.r.

[For the sites of the following dwellings, &c., referred to in the book, see the small capitals in the lower right-hand corner of the Map.]

A. Jonathan Corwin.

B. Samuel Shattock, John Cook, Isaac Sterns, John Bly.

C. Bartholomew Gedney.

D. Stephen Sewall.

E. Court House.

F. Rev. Nicholas Noyes.

G. John Hathorne.

H. George Corwin, High-sheriff.

I. Bridget Bishop.

J. Meeting-house.

K. Gedney's "Ship Tavern."

L. The Prison.

M. Samuel Beadle.

N. Rev. John Higginson.

O. Ann Pudeator, John Best.

P. Capt. John Higginson.

Q. The Town Common.

R. John Robinson.

S. Christopher Babbage.

T. Thomas Beadle.

U. Philip English.

W. Place of execution, "Witch Hill."

Note.—The grants are numbered on the Map with Roman numerals, the bounds being indicated by broken lines. They were all granted by the town of Salem, unless otherwise stated.

I. John Gould.

Sold by him to Capt. George Corwin, March 29, 1674; and by Capt. Corwin's widow sold to Philip Knight, Thomas Wilkins, Sr., Henry Wilkins, and John Willard, March 1, 1690.

II. Zaccheus Gould.

Sold by him to Capt. John Putnam before 1662; owned in 1692 by Capt. Putnam, Thomas Cave, Francis Elliot, John Nichols, Jr., Thomas Nichols, and William Way.

The above, together, comprised land granted by the General Court to Rowley, May 31, 1652, and laid out by Rowley to John and Zaccheus Gould.[i.xxiii]

III. Gov. John Endicott.

Ipswich-river Farm, 550 acres, granted by the General Court, Nov. 5, 1639; owned in 1692 by his grandsons, Zerubabel, Benjamin, and Joseph.

The General Court, Oct. 14, 1651, also granted to Gov. Endicott 300 acres on the southerly side of this farm, in "Blind Hole," on condition that he would set up copper-works. As the land appears afterwards to have been owned by John Porter, it is probable that the copper-mine was soon abandoned; but traces of it are still to be seen there.

IV. Gov. Richard Bellingham.

Granted by the General Court, Nov. 5, 1639.

V. Farmer John Porter.

Owned in 1692 by his son, Benjamin Porter. This includes a grant to Townsend Bishop, sold to John Porter in 1648; also 200 acres granted to John Porter, Sept. 30, 1647. That part in Topsfield was released by Topsfield to Benjamin Porter, May 2, 1687.

VI. Capt. Richard Davenport.

Granted Feb. 20, 1637, and Nov. 26, 1638; sold, with the Hathorne farm, to John Putnam, John Hathorne, Richard Hutchinson, and Daniel Rea, April 17, 1662.

VII. Capt. William Hathorne.

Granted Feb. 17, 1637; sold with the above.

VIII. John Putnam the Elder.

This comprises a grant of 100 acres to John Putnam, Jan. 20, 1641; 80 acres to Ralph Fogg, in 1636; 40 acres (formerly Richard Waterman's) to Thomas Lothrop, Nov. 29, 1642; and 30 acres to Ann Scarlett, in 1636. The whole owned by James and Jonathan Putnam in 1692.

IX. Daniel Rea.

Granted to him in 1636; owned by his grandson, Daniel Rea, in 1692.

X. Rev. Hugh Peters.

Granted Nov. 12, 1638; laid out June 15, 1674, being then in the possession of Capt. John Corwin; sold by Mrs. Margaret Corwin to Henry Brown, May 22, 1693.

XI. Capt. George Corwin.

Granted Aug. 21, 1648; sold (including 30 acres formerly John Bridgman's) to Job Swinnerton, Jr., and William Cantlebury, Jan. 18, 1661.[i.xxiv]

XII. Richard Hutchinson, John Thorndike, and Mr. Freeman.

Granted in 1636 and 1637; owned in 1692 by Joseph, son of Richard Hutchinson, and by Sarah, wife of Joseph Whipple, daughter of John, and grand-daughter of Richard Hutchinson.

XIII. Samuel Sharpe.

Granted Jan. 23, 1637; sold to John Porter, May 10, 1643; owned by his son, Israel Porter, in 1692.

XIV. John Holgrave.

Granted Nov. 26, 1638; sold to Jeffry Massey and Nicholas Woodberry, April 2, 1652; and to Joshua Rea, Jan. 1, 1657.

XV. William Alford.

Granted in 1636; sold to Henry Herrick before 1653.

XVI. Francis Weston.

Granted in 1636; sold by John Pease to Richard Ingersoll and William Haynes, in 1644.

XVII. Elias Stileman.

Granted in 1636; sold to Richard Hutchinson, June 1, 1648.

XVIII. Robert Goodell.

504 acres laid out to him, Feb. 13, 1652: comprising 40 acres granted to him "long since," and other parcels bought by him of the original grantees; viz., Joseph Grafton, John Sanders, Henry Herrick, William Bound, Robert Pease and his brother, Robert Cotta, William Walcott, Edmund Marshall, Thomas Antrum, Michael Shaflin, Thomas Venner, John Barber, Philemon Dickenson, and William Goose.

XIX. Job Swinnerton.

300 acres laid out, Jan. 5, 1697, to Job Swinnerton, Jr.; having been owned by his father, by grant and purchase, as early as 1650.

XX. Townsend Bishop.

Granted Jan. 11, 1636; sold to Francis Nurse, April 29, 1678.

XXI. Rev. Samuel Skelton.

Granted by the General Court, July 3, 1632; sold to John Porter, March 8, 1649; owned by the heirs of John Porter in 1692.[i.xxv]

XXII. John Winthrop, Jr.

Granted June 25, 1638; sold by his daughter to John Green, Aug. 9, 1683.

XXIII. Rev. Edward Norris.

Granted Jan. 21, 1640: sold to Elleanor Trusler, Aug. 7, 1654; to Joseph Pope, July 18, 1664.

XXIV. Robert Cole.

Granted Dec. 21, 1635; sold to Emanuel Downing before July 16th, 1638; conveyed by him to John and Adam Winthrop, in trust for himself and wife during their lives, and then for his son, George Downing, July 23, 1644; leased to John Procter in 1666; occupied by him and his son Benjamin in 1692.

XXV. Col. Thomas Reed.

Granted Feb. 16, 1636; sold to Daniel Epps, June 28, 1701, by Wait Winthrop, as attorney to Samuel Reed, only son and heir of Thomas Reed.

XXVI. John Humphrey.

Granted by the General Court, Nov. 7, 1632, May 6, 1635, and March 12, 1638, 1,500 acres, part in Salem and part in Lynn; sold, on execution, to Robert Saltonstall, Dec. 6, 1642, and by him sold to Stephen Winthrop, June 7, 1645, whose daughters—Margaret Willie and Judith Hancock—owned it in 1692: that part within the bounds of Salem is given in the Map according to the report of a committee, July 11, 1695.

Orchard Farm.

Granted by the General Court to Gov. Endicott; owned by his grandsons, John and Samuel, in 1692.

The Governor's Plain.

Granted to Gov. Endicott, Jan. 27, 1637, Dec. 23, 1639, and Feb. 5, 1644; including land granted under the name of "small lots."

Johnson's Plain.

Granted to Francis Johnson, Jan. 23, 1637.

[The bounds of farms are indicated by dotted lines, except where they coincide with the bounds of grants. The following are those given on the Map.]

1st, Between grants No. XI. and VII., and extending north of the Village bounds, and south as far as Andover Road,—about 500 acres; bought by Thomas and Nathaniel Putnam of Philip Cromwell, Walter Price and Thomas Cole, Jeffry Massey, John Reaves, Joseph and John Gardner, and Giles Corey; owned, in 1692, by Edward Putnam, Thomas Putnam, and John Putnam, Jr. This includes also 50 acres granted to Nathaniel Putnam, Nov. 19, 1649.

2d, At the northerly end of Grant No. VII., and extending north of the Village bounds,—100 acres, known as the "Ruck Farm;" granted to Thomas Ruck, May 27, 1654, and sold to Philip Knight and Thomas Cave, July 24, 1672.

3d, North of the "Ruck Farm,"—100 acres; sold by William Robinson to Richard Richards and William Hobbs, Jan. 1, 1660, and owned, in 1692, by William Hobbs and John Robinson.

4th, Next east, bounded northeast by Nichols Brook, and extending within the Village bounds,—200 acres; granted to Henry Bartholomew, and sold by him to William Nichols before 1652.

5th, East of the "Ruck Farm," and extending across the Village bounds,—about 150 acres; granted to John Putnam and Richard Graves. Part of this was sold by John Putnam to Capt. Thomas Lothrop, June 2, 1669, and was owned by Ezekiel Cheever in 1692: the rest was owned by John Putnam.

6th, East of the above, and south of the Nichols Farm,—60 acres, owned by Henry Kenny; also 50 acres granted to Job Swinnerton, given by him to his son, Dr. John Swinnerton, and sold to John Martin and John Dale, March 20, 1693.

7th, South of the above, and east of Grant No. VII.,—150 acres; granted to William Pester, July 16, 1638, and sold by Capt. William Trask to Robert Prince, Dec. 20, 1655.

8th, East of Grant No. VI., and extending north to Smith's Hill and south to Grant No. IX.,—about 400 acres; granted to Allen Kenniston, John Porter, and Thomas Smith, and owned, in 1692, by Daniel Andrew and Peter Cloyse.[i.xxvii]

9th, East and southeast of Smith's Hill,—500 acres; granted to Emanuel Downing in 1638 and 1649, and sold by him to John Porter, April 15, 1650. John Porter gave this farm to his son Joseph, upon his marriage with Anna daughter of William Hathorne.

10th, East of Frost-fish River, including the northerly end of Leach's Hill, and extending across Ipswich Road,—about 250 acres, known as the "Barney Farm;" originally granted to Richard Ingersoll, Jacob Barney, and Pascha Foote.

11th, South of the "Barney Farm,"—about 200 acres; granted to Lawrence, Richard, and John Leach; owned, in 1692, by John Leach.

12th, North of the "Barney Farm," and between grants No. XIII. and XIV.,—about 250 acres, known as "Gott's Corner;" granted to Charles Gott, Jeffry Massey, Thomas Watson, John Pickard, and Jacob Barney, and by them sold to John Porter. (Recently known as the "Burley Farm.")

13th, Eastward of the "Barney Farm,"—40 acres; originally granted to George Harris, and afterwards to Osmond Trask; owned, in 1692, by his son, John Trask.

14th, Next east, and extending across Ipswich Road,—40 acres; granted to Edward Bishop, Dec. 28, 1646; owned, in 1692, by his son, Edward Bishop, "the sawyer."

15th, At the northwest end of Felton's Hill, and extending across the Village line,—about 60 acres; owned by Nathaniel Putnam.

16th, Southeast of Grant No. XXIII.,—a farm of about 150 acres; owned by Giles Corey, including 50 acres bought by him of Robert Goodell, March 15, 1660, and 50 acres bought by him of Ezra and Nathaniel Clapp, of Dorchester, heirs of John Alderman, July 4, 1663.

17th, Northeast of the above,—150 acres granted to Mrs. Anna Higginson in 1636; sold by Rev. John Higginson to John Pickering, March 23, 1652; and by him to John Woody and Thomas Flint, Oct. 18, 1654; owned in 1692 by Thomas and Joseph Flint.

A.

Abbey, Thomas, 129.

Abbey, Samuel, ii. 200, 272.

Abbot, Joseph, 123.

Abbot, Nehemiah, ii. 128, 133, 208.

Aborn, Samuel, Jr., ii. 272.

Addington, Isaac, ii. 102, 474.

Afflicted children, ii. 112, 384, 465.

Age, reverence for, 217.

Agrippa, Henry Cornelius, 367.

Alford, William, 66.

Alden, John, ii. 208, 243-247, 255, 453.

Allen, James, 78-84; ii. 89, 309, 494, 550-553.

Allin, James, ii. 226.

America, the peopling of, 395.

Amsterdam, 460.

Andover, ii. 247.

Andrew, Daniel, 155, 214, 251, 270, 296, 319; ii. 59, 187, 272, 497,

550.

Andrews, Ann, ii. 170, 319.

Andrews, John, ii. 306.

Andrews, John, Jr., ii. 306.

Andrews, Joseph, ii. 306.

Andrews, William, ii. 306.

Andrews, Robert, 123.

Andros, Sir Edmund, ii. 99, 154.

Appleton, Samuel, 119; ii. 102, 250.

Apon, Peter, 342.

Arnold de Villa Nova, 342.

Arnold, Margaret, 356.

B.

Babbage, Christopher, ii. 184.

Bachelder, Mark, 123.

Bacheler, John, ii. 475.

Bacon, Francis, 383.

Bacon, Roger, 341.

Badger, John, 445.

Baker, Eben, 123.

Bailey, John, ii. 89, 310.

Balch, John, 129.

Balch, Joseph, 105.

Baptism: its subjects, 307.

Barbadoes, 287.

Barker, Abigail, ii. 349, 404.

Barnard, Thomas, ii. 477.

Barnes, Benjamin, ii. 499.

Barney, Jacob, 40, 140.

Barrett, Thomas, ii. 353.

Bartholomew, Henry, 206.

Bartholomew, William, 428.

Barton, Elizabeth, 343.

Bassett, William, ii. 207.

Batter, Edmund, 40, 46, 57.

Baxter, Richard, 352, 353, 355, 401, 459.

Bayley, James, 245-255, 278;

autograph, 280; ii. 514.

Bayley, Joseph, ii. 417.

Bayley, Thomas, 105.

Beadle, Samuel, 132; ii. 164, 181.

Beadle, Thomas, ii. 164, 170, 172.

Beale, William, ii. 141.

Beard, Thomas, 360.

Bears, 210.

Becket, John, ii. 267.

Beers, Richard, 104.

Bekker, Balthasar, 371.

Belcher, Jonathan, ii. 481.

Bellingham, Richard, 144.

Bentley, Richard, 372.

Bentley, William, ii. 143, 365, 377.

Best, John, ii. 329.

Best, John, Jr., ii. 329.

Bibber, Sarah, ii. 5, 205, 287.

Billerica, 9.

[i.xxx]Bishop, Bridget, 143, 191-197; ii. 114, 125-128, 253;

trial and execution, 256-267;

her house, 463.

Bishop, Edward, 142; ii. 272.

Bishop, Edward, 142, 191; ii. 253, 267, 466.

Bishop, Edward, 141, 143; ii. 128, 135, 383, 465, 478.

Bishop, Edward, 143.

Bishop, John, 8.

Bishop, Richard, 142.

Bishop, Sarah, ii. 128, 135.

Bishop, Thomas, 206.

Bishop, Townsend, 40, 66;

his house, 69-74, 96, 97;

autograph, 279; ii. 294, 467.

Black, Mary, ii. 128, 136.

Blackstone, Sir William, ii. 517.

Blazdell, Henry, 430.

Blazed trees, 43.

Bly, John, ii. 261, 266.

Bly, William, ii. 266.

Bloody Brook, 105.

Booth, Elizabeth, ii. 4, 465.

Bowden, Michael, ii. 467.

Bowditch, Nathaniel, 172.

Boyle, Robert, 359.

Boynton, Joseph, ii. 553.

Bradbury, Thomas, ii. 224, 450.

Bradbury, Mary, ii. 208, 224-238;

trial and condemnation, 324, 480.

Bradford, William, 122.

Bradstreet, Dudley, ii. 248, 347.

Bradstreet, John, 428.

Bradstreet, John, ii. 248, 347.

Bradstreet, Simon, 124, 139, 147;

autograph 279, 451, 454; ii. 99, 455, 456.

Braman, Milton P., ii. 516.

Brattle, William, ii. 450.

Braybrook, Samuel, ii. 30, 72, 202.

Bridges, Edmund, 186; ii. 94.

Bridges, Mary, ii. 349.

Bridges, Sarah, ii. 349.

Bridgham, Joseph, ii. 553.

Bridle-path, 43.

Britt, Mary, ii. 38.

Broom-making, 202.

Browne, Charles, 429.

Browne, Christopher, 438.

Browne, Henry, Jr., 55.

Browne, Sir Thomas, 357.

Browne, William, Jr., 226, 271.

Buckley, Sarah, ii. 187, 199, 349.

Buckley, Thomas, 105.

Buckley, William, ii. 199.

Burial of those executed, ii. 266, 293, 301, 312, 320.

Burnham, John, ii. 306.

Burnham, John, Jr., ii. 306.

Burroughs, Charles, ii. 478.

Burroughs, George, 255, 278;

autograph, 280;

arrest and examination, ii. 140-163;

trial and execution, 296-304, 319, 480, 482, 514.

Burt, Goody, 437.

Burton, John, 151.

Burton, Isaac, 152, 241.

Burton, Warren, 152.

Butler, Samuel, 352, 367.

Butler, William, ii. 306.

Buxton, Elizabeth, ii 272.

Buxton, John, 154, 262.

Byfield, Nathaniel, ii. 455.

C.

Calamy, Edmund, 283, 352.

Calef, Robert, ii. 32, 461, 490.

Candy, ii. 208, 215, 349.

Canoes, 61.

Cantlebury, William, 154.

Cantlebury, Ruth, ii. 18.

Capen, Joseph, ii. 326, 478.

Capital punishment, 377.

Cary, Elizabeth, ii. 208, 238, 453, 456.

Cary, Jonathan, ii. 238.

Carr, Ann, 253; ii. 465.

Carr, George, ii. 229.

Carr, James, ii. 232.

Carr, John, ii. 234.

Carr, Mary, 253.

Carr, Richard, ii. 230.

Carr, Sir Robert, 220.

Carr, William, ii. 234, 465.

Carrier, Martha, arrest and examination, ii. 208-215;

trial and execution, 296, 480.

Carrier, Sarah, ii. 209.

Carter, Bethiah, ii. 187.

Cartwright, George, 220.

Casco, 256.

Case, Humphrey, 154.

Castle Island, 102.

Cave, Thomas, 154.

Chapman, Simon, ii. 219.

Charter of Massachusetts, 15.

Checkley, Samuel, ii. 553.

Cheever, Ezekiel, 111.

Cheever, Ezekiel, Jr., 113, 117, 226, 299; ii. 15, 40, 550.

Cheever, Peter, 226.

Cheever, Samuel, 113; ii. 193, 478, 550.

[i.xxxi]Cheever, Thomas, 113.

Chickering, Henry, 74.

Chipman, John, 130.

Choate, John, ii. 306.

Choate, Thomas, ii. 306.

Church, Benjamin, 123.

Church-of-England Canon, 347.

Churchill, Sarah, ii. 4, 166, 169.

Clark, Peter, 171; ii. 513, 516.

Clark, Thomas, 425.

Clark, William, 40.

Cleaves, William, ii. 38, 336.

Clenton, Rachel, ii. 198.

Cloutman, William, ii. 267.

Cloyse, Peter, 269; ii. 9, 59, 94, 465, 485.

Cloyse, Sarah, ii. 60, 94, 101, 111, 326.

Cobbye, Goodman, 431.

Code, Roman, 374.

Cogswell, John, ii. 306.

Cogswell, John, Jr., ii. 306.

Cogswell, Jonathan, ii. 306.

Cogswell, William, ii. 306.

Cogswell, William, Jr., ii. 306.

Coldum, Clement, ii. 191.

Cole, Eunice, 437.

Colman, Benjamin, ii. 505.

Colson, Elizabeth, ii. 187.

Conant, Lot, 133.

Conant, Roger, 60, 63, 129.

Confessors, ii. 350, 397.

Constables, 21.

Cook, Elisha, ii. 497.

Cook, Elizabeth, ii. 272.

Cook, Henry, 57.

Cook, John, ii. 261.

Cook, Isaac, ii. 272.

Cook, Samuel, 230.

Copper mine, 45.

Corey, Giles, 181-191, 205; ii. 38, 44, 52, 114, 121, 128;

pressed to death, 334-343;

excommunicated, 343, 480, 483.

Corey, Martha, 190; ii. 38-42;

examination, 43-55, 111;

trial and execution, 324, 458, 507.

Corlet, Elijah, 111.

Corwin, George, 57, 98, 226.

Corwin, George, ii. 252, 470, 472.

Corwin, George, ii. 484.

Corwin, John, 55.

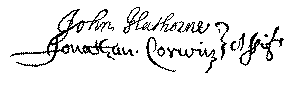

Corwin, Jonathan, 101; ii. 11, 13;

autograph, (29, 50, 69, 314,) 89, 101, 116, 157, 165, 250, 345;

letter to, 447, 485, 538.

Court House, ii. 253.

Court, Special, ii. 251, 254.

Court, Superior, of Judicature, ii. 349.

Cox, Mary, ii. 198.

Cox, Robert, 123.

Cradock, Matthew, 17.

Crane River Bridge, 194.

Cranmer, Archbishop, 343.

Creesy, John, 141.

Crosby, Henry, ii. 38, 45, 50, 124.

Cullender, Rose, 355.

D.

Daland, Benjamin, 230.

Dane, Francis, ii. 223, 330, 459, 478.

Dane, Deliverance, ii. 404.

Dane, John, ii. 475.

Dane, Nathaniel, ii. 460.

Danforth, Thomas, 461; ii. 101, 250, 349, 354, 455, 456.

Darby, Mrs., 260.

Darling, James, ii. 201.

Davenport, John, 385.

Davenport, Nathaniel, 121, 125-128.

Davenport, Richard, 100-103.

Davenport, True Cross, 101, 126.

Davis, Ephraim, 429.

Davis, James, 429.

De La Torre, 361.

Deane, Charles, 50.

Death-warrant, ii. 266.

Deland, Thorndike, ii. 267.

Demonology, 325, 327.

Dennison, Daniel, 147.

Derich, Mary, ii. 208.

Devil, 325, 338, 387.

Dexter, Henry M., 123.

Dodge, Granville M., 232.

Dodge, John, 129.

Dodge, Josiah, 105.

Dodge, William, 130.

Dodge, William, Jr., 129.

Dole, John, 444.

Dolliver, Ann, ii. 194.

Dolliver, William, ii. 194.

Douglas, Ann, ii. 179.

Dounton, William, ii. 274.

Downer, Robert, ii. 413.

Downing, Emanuel, 38-46;

autograph, 279.

Downing, Lucy, 39;

autograph, 279.

Downing, Sir George, 46.

Drake, Samuel G, ii. 26.

Dreams, ii. 411.

Druillettes, Gabriel, 37.

Dudley, Joseph, ii. 480.

Dudley, Thomas, 23.

[i.xxxii]Dugdale, Richard, 354.

Dummer, Jeremiah, ii. 553.

Dunny, Amey, 355.

Dunton, John, ii. 90, 471.

Dustin, Hannah, 9.

Dustin, Lydia, ii. 208.

Dustin, Sarah, ii. 208.

Dutch, Martha, ii. 179.

E.

Eames, Daniel, ii. 331.

Eames, Rebecca, ii. 324, 480.

Easty, Isaac, 241; ii. 56, 478.

Easty, John, 241.

Easty, Mary, ii. 60;

arrest, 128;

examination, 137;

re-arrest, 200-205;

trial and execution, 324-327, 480.

Education, 111, 213-216, 280, 284; ii. 221.

Eliot, Andrew, ii. 475.

Eliot, Daniel, ii. 191.

Eliot, Edmund, ii. 412.

Eliot, Elizabeth, 126.

Emerson, John, 444, 462.

Emory, George, 57.

Endicott, John, 16-20, 23, 32-38, 45, 50, 74-79, 95, 454.

Endicott, John, Jr., 74-78.

Endicott, Samuel, 32; ii. 231, 272, 307.

Endicott, Zerubabel, 32, 35, 58, 84-95.

Endicott, Zerubabel, ii. 230.

English, Mary, ii. 128, 136;

autograph, 313.

English, Philip, ii. 128, 140, 255;

autograph, 313, 470, 473, 478, 482.

Essex, Flower of, 104.

Eveleth, Joseph, ii. 306, 475.

F.

Fairfax, Edward, 347.

Fairfield, William, ii. 267.

Farmer, Hugh, 335, 390.

Farrar, Thomas, ii. 187.

Farrington, John, 123.

Faulkner, Abigail, ii. 330, 476, 480.

Fellows, John, ii. 306.

Felt, David, ii. 267.

Felton, Benjamin, 56.

Felton, John, 236; ii. 307.

Felton, Nathaniel, ii. 272, 307.

Felton, Nathaniel, Jr., ii. 307.

Filmer, Sir Robert, 373.

Fireplaces, 202.

First Church in Salem, 243, 246, 271; ii. 257, 290, 483.

Fisk, Thomas, ii. 284, 475.

Fisk, Thomas, Jr., ii. 475.

Fisk, William, ii. 475.

Fitch, Jabez, ii. 477.

Fletcher, Benjamin, ii. 242.

Flint, John, 141, 154.

Flint, Samuel, 229.

Flint, Thomas, 123, 188, 226, 270.

Flood, John, ii. 208, 331.

Fogg, Ralph, 57.

Forests, 7, 27.

Fosdick, Elizabeth, ii. 208.

Foster, Abraham, ii. 384.

Foster, Ann, ii. 351, 398, 480.

Foster, Isaac, ii. 306.

Foster, John, ii. 466.

Foster, Reginald, ii. 306.

Fowler, Joseph, ii. 206.

Fowler, Philip, ii. 206.

Fowler, Samuel P., ii. 206.

Fox, Rebecca, ii. 188.

Foxcroft, Francis, ii. 455.

Frayll, Samuel, ii. 307.

Fuller, Benjamin, ii. 177.

Fuller, Jacob, 227.

Fuller, John, ii. 280.

Fuller, Samuel, ii. 177.

Fuller, Thomas, 187, 227, 250, 288; ii. 25.

Fuller, Thomas, Jr., 288; ii. 173.

G.

Gallop, John, 122.

Game, pursuit of, 208.

Gammon, ——, ii. 354.

Gardiner, Sir Christopher, 68.

Gardner, Joseph, 45, 122, 123, 124.

Gardner, Samuel, 45.

Gardner, Thomas, 45, 117.

Gaskill, Edward, ii. 307.

Gaskill, Samuel, ii. 307.

Gaule, John, 363.

Gedney, Bartholomew, 271; ii. 89, 243, 244, 250, 251, 254, 496.

Gedney, John, 158, 258; ii. 254.

Gedney, John, Jr., ii. 254.

Gedney, Susannah, ii. 254, 264.

General Court responsible for the executions, ii. 268.

Gerbert (Sylvester II.), 339.

Gerrish, Joseph, ii. 478, 550.

Gidding, Samuel, ii. 306.

Gifford, Margaret, 437.

[i.xxxiii]Gingle, John, 144.

Glover, Goody, 454.

Gloyd, John, 186, 189.

Godfrey, John, 428-436.

Good, Dorcas, examination of, ii. 71, 111.

Good, Sarah, ii. 11;

examination of, 12-17;

trial and execution, 268, 269, 480.

Good, William, ii. 12, 481.

Goodell, Abner C., 141.

Goodell, Robert, 141.

Goodhew, William, ii. 306.

Goodwin, Mr., 454.

Governors of Massachusetts, time of election by charter, 17.

Governor's Plain, 24.

Gould, Nathan, 432.

Gould, Thomas, 188.

Grants, policy of, 22.

Gray, William, 130.

Graves, Thomas, ii. 455.

Green, Joseph, 9, 146, 170; ii. 199, 477, 506, 516.

Greenslit, John, ii. 298.

Greenslit, Thomas, ii. 298.

Griggs, William, ii. 4, 6.

Griggs, Goody, ii. 111.

Grover, Edmund, 31.

H.

Hakins, Nicholas, 123.

Hale, John, 195-197, 299, 452; ii. 43, 70, 257, 345, 475, 478, 550.

Hale, Sir Matthew, 355; ii. 269.

Halliwell, Henry, 364.

Handwriting, 214, 277-281; ii. 55.

Harding, Edward, 123.

Hardy, George, 443.

Harris, Benjamin, ii. 90.

Harris, George, 63.

Harsnett, Samuel, 369.

Hart, Thomas, ii. 352.

Hart, Elizabeth, ii. 187.

Harwood, John, ii. 275.

Hathorne, John, 40, 99, 271; ii. 11, 13, 20, 28;

autograph, (29, 50, 69, 314), 43, 60, 89, 101, 102, 116, 241, 250.

Hathorne, William, 46, 57, 99.

Haverhill, 9.

Hawkes, Mrs., ii. 216, 349.

Haynes, John, 139.

Haynes, Richard, 138, 140.

Haynes, Thomas, 139, 260, 431; ii. 132, 465.

Haynes, William, 40, 138.

Hazeldon, John, 429.

Herrick, George, ii. 49, 60, 71, 202, 252, 274, 471.

Herrick, Henry, 66, 153.

Herrick, Henry, ii. 475.

Herrick, Joseph, 129, 141, 269, 270; ii. 12, 28, 272.

Hibbert's Philosophy of Apparitions, ii. 518.

Hibbins, Ann, 420-427, 453.

Higginson, John, 271, 273; ii. 89, 193, 478, 550.

Highways, 43, 212.

Highways, surveyors of, 21.

Hill, Captain, ii. 244.

Hoar, Dorcas, ii. 140, 144, 384, 480.

Hobbs, Abigail, ii. 114, 128, 480, 481.

Hobbs, Deliverance, ii. 128, 161.

Hobbs, William, ii. 114, 128, 130.

Holgrave, John, 63.

Holyoke, Edward, 156.

Holyoke, Edward Augustus, 156; ii. 377.

Hopkins, Matthew, 351.

Horace, 366.

Horse Bridge, 234.

Houchins, Jeremiah, 74.

Houlton, Benjamin, ii. 275, 280, 281.

Houlton, James, ii. 307.

Houlton, Joseph, 86, 147, 243, 270; ii. 272, 496.

Houlton, Joseph, Jr., 123; ii. 272.

Houlton, Samuel, 148, 223.

Houlton, Sarah, ii. 281, 495, 506.

Houlton, town of, 151.

Houses, 184.

How, Elizabeth, ii. 208;

examination of, 216-223;

trial and execution, 268, 270, 480.

How, James, Sr., ii. 221.

How, John, 241.

Howard, John, ii. 198.

Howard, Nathaniel, 141.

Hubbard, Elizabeth, ii. 4, 191.

Hubbard, William, ii. 193, 477.

Hudson, William, 425.

Hungerford, Earl of, 343.

Hunniwell, Richard, ii. 298.

Hunt, Ephraim, ii. 553.

Huskings, 201.

Hutchinson, Benjamin, 172; ii. 151, 197, 201.

Hutchinson, Edward, 425.

Hutchinson, Elisha, ii. 150.

Hutchinson, Israel, 223, 228.

[i.xxxiv]Hutchinson, Joseph, 243, 250, 270, 285, 319; ii. 11, 28, 33, 272, 393,

545, 550.

Hutchinson, Lydia, ii. 272.

Hutchinson, Richard, 27, 40, 86, 137.

Hutchinson, Thomas, History of Massachusetts, 415.

I.

Indians, 7, 25, 62, 286.

Ingersoll, Hannah, 166, 261; ii. 192.

Ingersoll, John, 40, 172; ii. 171.

Ingersoll, Joseph, ii. 129.

Ingersoll, Nathaniel, 35, 86, 165-179, 225, 244, 249, 251, 259, 261;

autograph, 280, 288, 294, 301, 303;

ordination as deacon, 305; ii. 11, 33, 42, 60, 73, 100, 112, 114, 128, 132, 140, 499.

Ingersoll, Sarah, ii. 169.

Ingersoll, Richard, 36, 40, 138.

Ingersoll's Point, 138.

Inquest, jury of, ii. 178.

Ipswich road, 43.

Ireson, Benjamin, ii. 208.

Iron works, 147.

Izard, Ann, ii. 520.

J.

Jackson, John, ii. 198, 223.

Jackson, John, Jr., ii. 198, 223.

Jacobs, George, 198; ii. 4;

arrest and examination, 164-172, 274;

execution, 296, 312, 382, 480.

Jacobs, George, Jr., 198; ii. 187.

Jacobs, Margaret, ii. 164, 172, 315, 349, 353, 466.

Jacobs, Rebecca, ii. 187, 349.

Jacobs, Thomas, ii. 207.

James I., 368, 375, 410.

Jewell, John, 345.

Jewett, Nehemiah, ii. 553.

Joan of Arc, 343.

Jones, Hugh, 91.

Jones, Margaret, 415, 453.

John Indian, ii. 2, 95, 106, 241.

Johnson, Elizabeth, ii. 349.

Johnson, Elizabeth, Jr., ii. 349.

Johnson, Francis, 40.

Johnson, Isaac, 121, 122.

Johnson, Samuel, 357.

Johnson, Captain, 425.

Jovius Paulus, 367.

Judges, ii. 354.

Jury to examine the bodies of prisoners, ii. 274.

Jury of trials, ii. 284, 474.

K.

Kembal, John, ii. 412.

Kenny, Henry, 251; ii. 61.

Kepler, John, 345.

King, Daniel, ii. 181.

King, Joseph, 105.

King, Margaret, 196.

Kircher, Athanasius, 388.

Kitchen, John, 205.

Knight, Charles, 123.

Knight, John, 138.

Knight, Jonathan, ii. 177.

Knight, Philip, ii. 177.

Knight, Walter, 35.

Knowlton, Joseph, ii. 220.

L.

Lacy, Mary, ii. 400, 480.

Lacy, Mary, Jr., ii. 349, 401.

Lamb, Dr., 348.

Land, policy concerning, 16, 22;

given up to towns, 20;

clearing of, 26;

disposition of, to children, 158;

value of, 159.

Landlord, 218.

Laodicea, Council of, 375.

Law under which the trials took place, ii. 256, 268, 360.

Lawson, Deodat, 268-284;

autograph, 280; ii. 7, 70, 73;

his sermon, 76-92, 515, 525-537.

Lawson, Thomas, 283.

Law-suits, 232.

Layman, Paul, 361.

Leach, John, 141.

Leach, Lawrence, 141.

Leach, Robert, 129.

Leach, Sarah, ii. 272.

Lecture-day, 313, 450; ii. 76.

Lewis, Mercy, ii. 4, 287;

autograph, 313.

Lewis, Rev. Mr., 353.

Lexington, 229.

Lightning, 72.

Locke, John, 372.

Locker, George, ii. 12, 307.

Lothrop, Ellen, 111.

Lothrop, Thomas, 100, 103-117.

Louder, John, ii. 264.

[i.xxxv]Lovkine, Thomas, ii. 306.

Low, Thomas, ii. 306.

Luther, Martin, 344.

M.

Mackenzie, Sir George, 350.

Magistrates, ii. 354.

Manning, Jacob, ii. 142.

Maple-sugar, 203.

Marblehead, ii. 519.

March, John, ii. 234.

Marriage, early, 160; ii. 236.

Marsh, Samuel, ii. 307.

Marsh, Zachariah, ii. 307.

Marshall, Benjamin, ii. 306.

Marshall, Samuel, 122.

Marston, Mary, ii. 349.

Martin, Susannah, 427;

arrest and examination, ii. 145;

trial and execution, 268.

Mascon, Devil of, 359.

Mason, Thomas, ii. 267.

Maverick, Samuel, 220.

Maverick, Samuel, Jr., ii. 228.

Mather, Cotton, 112, 384, 391, 454; ii. 89, 211, 250, 257, 299, 341, 366, 487, 494, 503, 553.

Mather, Increase, ii. 89, 299, 308, 345, 404, 494, 553.

Mechanical occupations, 224.

Mede, Joseph, 394.

Medical profession, ii. 361.

Meeting, intermission of, on the Lord's Day, 207.

Meeting-house of Salem Village, 243, 244, 285.

Meeting-house of Salem Village, scenes at, 263; ii. 34, 60, 94, 510.

Meeting-house of First Church in Salem, scenes at, ii. 111, 257, 290.

Melancthon, Philip, 344.

Middlecot, Richard, ii. 553.

Milton, John, 387, 467.

Ministers, ii. 267, 362.

Minot, Stephen, 125.

Mirage, 386.

Mitchel, Jonathan, 434, 437.

Moody, Lady Deborah, 57, 183.

Moody, Joshua, ii. 309.

Moore, Captain, 187.

Moore, Caleb, 188.

Moore, Jane, 188.

More, Henry, 400.

Morrel, Robert, ii. 153, 191.

Morrell, Sarah, ii. 140, 144.

Morse, Anthony, 447.

Morse, Elizabeth, 449-453.

Morse, William, 438.

Morton, Charles ii. 89.

Mosely, Samuel, 121.

Moulton, John, ii. 38, 336, 478.

Moulton, Robert, 40.

Moulton, Robert, Jr., 40.

Moxon, George, 419.

N.

Narragansett expedition, 118-135.

Narragansett townships, 133.

Nauscopy, 386.

Navigation, early New-England, 440.

Neal, Joseph, ii. 164, 274.

Needham, Anthony, 155, 184, 226, 236; ii. 48.

Newbury, 9.

New-Haven Phantom-ship, 384.

New-York Negro Plot, ii. 437.

Newman, Antipas, 58.

New Salem, 149.

Newton, Thomas, ii. 254;

autograph, 314.

Nichols, Isaac, ii. 177.

Nichols, John, 241, ii. 133.

Nichols, Richard, 220.

Nichols, William, 154.

Norfolk, old county of, ii. 228.

Norris, Edward, 57, 237.

Norris, Edward, Jr., 205.

Norton, John, 423, 425; ii. 450.

Noyes, Nicholas, 117, 271, 299; ii. 43, 48, 55, 89, 170, 172, 184, 245, 253, 269, 290, 292, 365, 485, 550;

autograph, 314.

Numa Pompilius, 330.

Nurse, Francis, 79, 84, 91, 214, 287, 319, 320; ii. 9, 467.

Nurse, Rebecca, 80;

her arrest and examination, ii. 56-71, 111, 136;

trial, 268, 270-289;

excommunication, 290;

execution, 292, 480, 483.

Nurse, Samuel, 80; ii. 57, 288, 479, 485, 497, 506, 545-553.

Nurse, Sarah, 80; ii. 287, 467.

O.

Obinson, Mrs., ii. 456.

Ocular fascination, 412; ii. 520.

Oliver, Christian, ii. 267.

Oliver, Mary, 420.

Oliver, Peter, 425.

[i.xxxvi]Oliver, Thomas, 143, 191; ii. 253, 267.

Orchard Farm, 24, 87.

Orne, John, 57.

Osborne, Hannah, ii. 272.

Osborne, William, 152, 227; ii. 272.

Osburn, Alexander, ii. 18.

Osburn, John, ii. 19.

Osburn, Sarah, ii. 11, 17;

examination, 20;

death, 32.

Osgood, Mary, ii. 349, 404, 406.

Osgood, William, 432.

P.

Page, Abraham, 139.

Paine, Elizabeth, ii. 208.

Paine, Stephen, ii. 208.

Paine, Robert, 423; ii. 449.

Palfrey, Peter, 63, 129.

Palfrey, John G., 125.

Palisadoes, 31.

Parker, Alice, ii. 179-185;

trial and execution, 324.

Parker, John, ii. 179, 181.

Parker, John, 189; ii. 38, 48, 124.

Parker, Mary, trial and execution, ii. 324, 325, 480.

Parris, Elizabeth, ii. 3.

Parris, Samuel, 170, 172, 278;

autograph, 280, 286-320; ii. 1, 7, 9, 25, 31, 43, 49, 55, 92, 275, 290, 485-503, 515, 545-553.

Parris, Thomas, 286; ii. 499.

Parsonage of Salem Village, 243, 386; ii. 74, 466, 493.

Parsons, Hugh, 419.

Parsons, Mary, 418.

Partridge, John, ii. 150.

Payson, Edward, ii. 218, 494, 553.

Peabody, John, ii. 475.

Peach, Barnard, ii. 414.

Pease, Robert, ii. 208.

Peele, William, ii. 267.

Peine forte et dure, ii. 338, 484.

Peirce, Joseph, 123.

Pendleton, Bryan, 256.

Penn, William, 414.

Perkins, Isaac, ii. 306.

Perkins, Nathaniel, ii. 306.

Perkins, Thomas, ii. 475.

Perkins, William, 362.

Perley, Samuel, ii. 216.

Perley, Thomas, ii. 475.

Peters, Elizabeth, 50-53, 57.

Peters, Hugh, 47, 50, 51-59.

Pettingell, Richard, 40.

Phelps, Henry, 237.

Phelps, John, 187.

Phips, Sir William, 131, 451; ii. 99, 250;

autograph, 314, 345.

Phips, Spencer, ii. 482.

Phillips, Margaret, ii. 272.

Phillips, Samuel, 299; ii. 218, 494, 553.

Phillips, Tabitha, ii. 272.

Phillips, Walter, ii. 272.

Pickering, John, 46.

Pickering, Timothy, 46, 227.

Pierpont, James, 384.

Pike, John, ii. 226, 229.

Pike, Robert, ii. 226, 228, 250, 449, 538-544.

Pikeworth, 123; ii. 329.

Pitcher, Moll, ii. 521.

Pit-saw, 191.

Poindexter, ii. 185.

Poland, James, 188.

Pope, Gertrude, 236.

Pope, Joseph, 237, 238; ii. 65, 496.

Pope Innocent VIII., 342.

Porter, Benjamin, 141.

Porter, Elizabeth, ii. 272.

Porter, Israel, 141; ii. 59, 272, 550.

Porter, John, 40, 136.

Porter, John, Jr., 219.

Porter, John, ii. 207.

Porter, Joseph, 270, 296, 319.

Porter, Moses, 223, 230.

Post, Hannah, ii. 349.

Post, Mary, ii. 349, 480.

Powell, Caleb, 439.

Pratt, Francis, 428.

Prescott, Peter, 129, 316; ii. 153.

Preston, Thomas, 80, 91; ii. 11, 57, 496, 550.

Price, Walter, 226.

Prince, James, ii. 17.

Prince, Joseph, ii. 17.

Prince, Robert, ii. 17.

Prison, ii. 254.

Procter, Benjamin, ii. 207.

Procter, Elizabeth, arrest and examination, ii. 101-111;

trial and condemnation, 296, 312, 466.

Procter, John, 179, 184, 227; ii. 4, 106, 111;

trial and execution, 296, 304-312;

autograph, 313, 458, 480.

Procter, Joseph, ii. 306.

Procter, Sarah, ii. 207.

Procter, William, ii. 208, 311.

Procter's Corner, 49.

Pronunciation, ii. 233.

Pudeator, Ann, ii. 179, 185, 300;

trial and execution, 324, 329.

Pudeator, Jacob, ii. 185, 329.

[i.xxxvii]Puppets, 408, ii. 12, 266.

Putnam, Ann, 253; ii. 5, 61, 69, 74, 177, 229, 236, 276, 282, 465, 495, 506.

Putnam, Ann, Jr., 214; ii. 3, 8, 40, 190;

autograph, 313, 341, 511, 509-512.

Putnam, Archelaus, 164.

Putnam, Benjamin, 164; ii. 72, 272, 481.

Putnam, Daniel, 164.

Putnam, David, 227.

Putnam, Edward, 8, 161-164, 288, 302; ii. 11, 40, 44, 60, 71, 203, 288, 465.

Putnam, Eleazer, 132; ii. 152.

Putnam, Enoch, 229.

Putnam, Holyoke, 9.

Putnam, Israel, 160, 164, 227, 238.

Putnam, James, ii. 506.

Putnam, Jeremiah, 229.

Putnam, John, 34, 40, 155.

Putnam, John, 34, 155, 157, 241, 250, 251, 258, 267, 270, 284, 287,

316, 317; ii. 272, 359, 496, 550.

Putnam, John, Jr., 259; ii. 4, 172, 202, 506.

Putnam, John, 3d, ii. 506.

Putnam, Jonathan, 269; ii. 60, 71, 201, 272.

Putnam, Joseph, 160, 296, 319; ii. 9, 272, 457, 497.

Putnam, Lydia, ii. 272.

Putnam, Miriam, ii. 295.

Putnam, Nathaniel, 84, 86, 155, 157, 186, 198, 236, 250, 288, 296; ii. 33, 128, 178, 271.

Putnam, Orin, ii. 295.

Putnam, Perley, 230.

Putnam, Phinehas, ii. 295.

Putnam, Rebecca, 267; ii. 272, 359.

Putnam, Rufus, 227.

Putnam, Samuel, 223.

Putnam, Sarah, ii. 272.

Putnam, Susannah, 143.

Putnam, Thomas, 155, 226, 250, 251, 259;

autograph, 279.

Putnam, Thomas, 129, 225, 227, 236, 253;

autograph, 279, 281, 316; ii. 3, 4, 11, 28, 55, 140, 232, 341, 464, 465, 506.

Putnam, William Lowell, 232.

Q.

Queen Elizabeth, 345.

Quick, John, 283.

R.

Rabbits, 209.

Raising of a house, 201.

Rawson, Edward, 425, 450.

Raymond, John, 66.

Raymond, John, 129, 134; ii. 465.

Raymond, John W., 232.

Raymond, Richard, 141.

Raymond, Thomas, 129, 133, 141.

Raymond, William, 129, 132, 143.

Raymond, William, Jr., ii. 192.

Rea, Bethiah, 113, 116.

Rea, Daniel, 40, 113, 140.

Rea, Daniel, Jr., 288; ii. 272.

Rea, Hepzibah, ii. 272.

Rea, Joshua, 114, 140, 141, 287, 288; ii. 272, 545.

Rea, Sarah, ii. 272.

Read, Christopher, 123.

Read, Thomas, 49.

Records of Salem Village, 269, 272, 273-278.

Redemptioners, ii. 18.

Reed, Nicholas, 8.

Reed, Philip, 437.

Reed, Wilmot, arrest, ii. 208;

trial and execution, 324, 325.

Reinolds, Alexius, 91.

Remigius, 344.

Rice, Charles B., ii. 513.

Rice, Sarah, ii. 208.

Richards, John, ii. 251, 349.

Richardson, Mr., 442.

Richardson, Mary, 448.

Ring, Jarvis, ii. 414.

Rist, Nicholas, ii. 352.

Roads, 43.

Robinson, John, ii. 181, 184.

Rogers, John, ii. 477.

Rogers, Thomas, 443.

Rolfe, Benjamin, 9; ii. 478.

Roots, Susannah, ii. 207.

Ropes, Nathaniel, 237.

Rose, Richard, ii. 171.

Royal Neck, 58.

Ruck, Thomas, 57.

Rule, Margaret, ii. 489.

Russell, James, ii. 102.

Russell, William, 80.

S.

Salem Farms, 136.

Salem Village, 199, 216, 223, 224, 233, 234, 242, 248, 269-278, 298,

[i.xxxviii]312, 321, 322; ii. 485, 513.

Saltonstall, Nathaniel, ii. 251, 455.

Satan, 325, 338.

Sargent, Peter, ii. 251.

Savage, James, 50, 384.

Saw-pit, 191.

Sawyers, 191.

Sayer, Samuel, ii. 475.

Scarlett, Benjamin, 32.

Science, physical, 380.

Scott, Margaret, trial and execution, ii. 324, 325.

Scott, Reginald, 368, 410.

Scott, Sir Walter, 335.

Scottow, Joshua, 424, 425; ii. 298.

Scriptures, King James's Translation of, 375.

Scruggs, Margery, 66.

Scruggs, Rachel, 65.

Scruggs, Thomas, 64, 130.

Sears, Ann, ii. 208.

Seating the meeting-house, 217; ii. 506.

Seely, Robert, 122.

Settlers, provision of land for, 16.

Sewall, Mitchel, ii. 481.

Sewall, Samuel, ii. 102, 111, 157, 251, 441, 497.

Sewall, Samuel, ii. 481.

Sewall, Stephen, 57; ii. 3, 230, 384, 487, 497.

Shakespeare, William, 379, 467.

Sharp, Samuel, 46, 57, 388.

Shattuck, Samuel, 193; ii. 180, 259.

Shaw, Israel, ii. 465.

Sheldon, Godfrey, 8.

Sheldon, Susannah, ii. 4, 322.

Shepard, John, ii. 465.

Shepard, Rebecca, ii. 275, 280.

Sherringham, Robert, 356.

Shippen, Mr., 261.

Ship Tavern, ii. 254.

Shirley, William, ii. 482.

Shovel-board, 196, 204.

Sibley, John, 141, 154.

Sibley, John L., 141.

Sibley, Mary, ii. 95, 97.

Sibley, Samuel, 259, 262; ii. 97, 465.

Sibley, William, 262; ii. 18.

Silsbee, Nathaniel, ii. 267.

Sinclair, George, 350.

Singletary, Jonathan, 433.

Skelton, Samuel, 57, 85.

Skerry, Henry, 259.

Sleighs, 203.

Small, Thomas, 154; ii. 19.

Smith, George, ii. 307.

Smith, Thomas, 105.

Soames, Abigail, ii. 208.

Soames, Joseph, 123.

Spaulding, Willard, 237.

Spencer, John, 432.

Spenser, Edmund, 346, 365.

Sprenger, James, 361.

Stacy, William, ii. 263.

Stearns, Isaac, ii. 263.

Stileman, Elias, 40, 86.

Stone, Samuel, ii. 307.

Story, Joseph, ii. 440.

Story, William, ii. 306.

Stoughton, William, 125; ii. 157, 250, 301, 349, 355.

Sunday patrol, 40.

Surey Demoniac, 354.

Sweden, King of, 344.

Swinnerton, Esther, ii. 272.

Swinnerton, Job, 140, 270.

Swinnerton, Job, ii. 272.

Swinnerton, Ruth, ii. 495.

Switchell, Abraham, 123.

Syllogism, 381.

Symmes, Thomas, ii. 478.

Symmes, Zachariah, ii. 478.

Symonds, John, ii. 377.

Symonds, Samuel, 433.

Symonds, William, 433.

T.

Tanner, Adam, 361.

Tarbell, John, 80, 91, 288; ii. 57, 287, 486, 497, 506, 545-553.

Taylor, Benjamin, 182.

Taylor, Zachary, 124.

Tears, trial by, 409.

Thacher, Mrs., ii. 345, 448, 453.

Thomasius, Christian, 373.

Thompson, William, ii. 306.

Tibullus, Elegy, 337.

Titcomb, Elizabeth, 444.

Tituba, ii. 2, 11;

examination and confession, 23, 32, 255.

Tookey, Job, arrest, ii. 208;

examination, 223, 349.

Toothacre, Mrs., ii. 208.

Topsfield, controversy with, 238.

Torrey, Samuel, ii. 494, 553.

Torrey, William, 450; ii. 553.

Towne, Jacob, 241; ii. 56.

Towne, John, 241; ii. 56.

Towne, Joseph, 241; ii. 56.

Towne, William, ii. 466.

Towns, 20.

Train-band, 100, 224.

Training-field, 176, 178, 225.

[i.xxxix]Trask, Edward, 105.

Trask, William, 34, 64, 129.

Travel, modes of, 43, 61, 203.

Troopers, company of, 226.

Trusler, Eleanor, 237.

Tucker, John, 444.

Tucker, Mary, 448.

Tufts, James, 105.

Turner, Sharon, 375.

Twiss, William, 395.

Tycho Brahe, 345.

Tyler, Hannah, ii. 349, 404.

Tyler, Mary, ii. 349, 404.

Tyng, Edward, 125.

U.

Upham, Phinehas, 118, 122.

Upton family, 155.

Urbain Grandier, 348.

Usher, Hezekiah, ii. 453.

V.

Varney, Thomas, ii. 306.

Verrin, Hilliard, 40.

Verrin, Joshua, 40.

Verrin, Nathaniel, 156, 287.

Verrin, Philip, 40, 63.

Verrin, Philip, Jr., 40.

Vigilance Committee, ii. 286.

Villalpando, Don Francisco Torreblanca, 361.

Virgil, 336, 413.

W.

Wade, Thomas, ii. 337.

Wadsworth, Benjamin, ii. 505.

Wadsworth, Benjamin, ii. 516.

Wagstaff, John, 370.

Wainwright, Simon, 9.

Walcot, Abraham, 188.

Walcot, Jonathan, 155, 225, 270; ii. 3, 100, 140, 464, 466.

Walcot, Jonathan, Jr., ii. 125, 550.

Walcot, Mary, ii. 3, 465.

Walker, Richard, ii. 207.

Walley, John, ii. 553.

Ward, George A., 98.

Wardwell, Mary, ii. 349.

Wardwell, Samuel, trial and execution, ii. 324, 384, 480.

Wardwell, Sarah, ii. 349.

Warren, Mary, ii. 4, 114, 128.

Warren, Sarah, ii. 17.

Wassalbe, Bridget, 191.

Waterman, Richard, 60.

Watson's Annals of Philadelphia, 414.

Watts, Isaac, ii. 516.

Watts, Jeremiah, 179.

Way, Aaron, 145; ii. 68, 177.

Way, William, ii. 493.

Weld, Daniel, 57.

Wells, town of, 256.

Wesley, John, ii. 518.

Westgate, John, ii. 181.

Weston, Francis, 60.

Wheelwright, John, ii. 228.

Whitaker, Abraham, 429.

White, James, ii. 306.

White, John, 389.

Whittier, John G., ii. 444.

Whittredge, Mary, ii. 187, 197, 199.

Wierus, John, 368, 376.

Wilds, John, ii. 128, 135.

Wilds, Sarah, arrest and examination, ii. 135;

trial and execution, 268, 480.

Wilds, William, 143; ii. 135.

Wilderness, opening of, 26.

Wilkins, Benjamin, 227; ii. 173, 550.

Wilkins, Bray, 143-146, 214, 309; ii. 173, 174.

Wilkins, Daniel, ii. 174, 179.

Wilkins, Hannah, 309.

Wilkins, Henry, ii. 174.

Wilkins, Samuel, ii. 173.

Wilkins, Thomas, 154, 227, 316; ii. 491-495, 506, 546-553.

Willard, John, arrest, ii. 172-179;

trial and execution, 321, 480.

Willard, Margaret, ii. 466.

Willard, Samuel, ii. 89, 289, 309, 494, 550-553.

Willard, Simon, ii. 210.

Williams, Abigail, ii. 3, 7, 46, 393.

Williams, Nathaniel, ii. 553.

Williams, Roger, 50, 56, 68.

Wilson, Robert, 105.

Wilson, Sarah, ii. 404.

Wills, 65, 75, 78, 92, 137, 162, 175, 425; ii. 304, 312, 511.

Wills Hill, 26, 144.

Winslow, Josiah, 119.

Winthrop, Fitz John, 54.

Winthrop, John, 17, 23, 39, 95, 454.

Winthrop, John, Jr., 39, 50, 58.

Winthrop, Wait, 54; ii. 251, 349, 497.

Wise, John, ii. 304, 306;

autograph, 314, 477, 494.

[i.xl]Witch, 402.

Witchcraft, 337;

law relating to, ii. 256, 516.

Witch-imp, 406.

Witch-mark, 405.

Witch-puppets, 408.

Witch Hill, ii. 376-380.

Witch of Endor, 333.

Wood, Anthony, 370.

Woodbridge, John, 438.

Wooden Bridge, 234.

Woodbury, Humphrey, 141.

Woodbury, John, 129.

Woodbury, Nicholas, 98.

Woodbury, Peter, 105.

Woodbury, William, 141.

Wooleston River, 23.

Wolf-pits, 212.

Wolves, 211.

Y.

Young, William, 51.

IT is one of the distinguishing characteristics of the human being, that he loves to contemplate the scenes of the past, and desires to have his own history borne down to the future. This, like all the other propensities of our nature, is accompanied by faculties to secure its gratification. The gift of speech, by which the parent can convey information to the child—the old transmit intelligence to the young—is an indication that it is the design of the Author of our being that we should receive from those passing away the narrative of their experience, and communicate the results of our own to the generations that succeed us. All nations have, to a greater or less degree, been faithful to their trust in using the gift to fulfil the design of the Giver. It is impossible to name a people who do not possess cherished traditions that have descended from their early ancestors.

Although it is generally considered that the invention of a system of arbitrary and external signs to communicate thought is one of the greatest and most[i.2] arduous achievements of human ingenuity, yet so universal is the disposition to make future generations acquainted with our condition and history,—a disposition the efficient cause of which can only be found in a sense of the value of such knowledge,—that you can scarcely find a people on the face of the globe, who have not contrived, by some means or other, from the rude monument of shapeless rock to the most perfect alphabetical language, to communicate with posterity; thus declaring, as with the voice of Nature herself, that it is desirable and proper that all men should know as much as possible of the character, actions, and fortunes of their predecessors on the stage of life.

It is not difficult to discern the end for which this disposition to preserve for the future and contemplate the past was imparted to us. If all that we knew were what is taught by our individual experience, our minds would have but little, comparatively, to exercise and expand them, and our characters would be the result of the limited influences embraced within the narrow sphere of our particular and immediate relations and circumstances. But, as our notice is extended in the observation of those who have lived before us, our materials for reflection and sources of instruction are multiplied. The virtues we admire in our ancestors not only adorn and dignify their names, but win us to their imitation. Their prosperity and happiness spread abroad a diffusive light that reaches us, and brightens our condition. The wisdom that[i.3] guided their footsteps becomes, at the same time, a lamp to our path. The observation of the errors of their course, and of the consequent disappointments and sufferings that befell them, enables us to pass in safety through rocks and ledges on which they were shipwrecked; and, while we grieve to see them eating the bitter fruits of their own ignorance and folly as well as vices and crimes, we can seize the benefit of their experience without paying the price at which they purchased it.

In the desire which every man feels to learn the history, and be instructed by the example, of his predecessors, and in the accompanying disposition, with the means of carrying it into effect, to transmit a knowledge of himself and his own times to his successors, we discover the wise and admirable arrangement of a providence which removes the worn-out individual to a better country, but leaves the acquisitions of his mind and the benefit of his experience as an accumulating and common fund for the use of his posterity; which has secured the continued renovation of the race, without the loss of the wisdom of each generation.

These considerations suggest the true definition of history. It is the instrument by which the results of the great experiment of human action on this theatre of being are collected and transmitted from age to age. Speaking through the records of history, the generations that have gone warn and guide the generations that follow. History is the Past, teaching Philosophy to the Present, for the Future.[i.4]

Since this is the true and proper design of history, it assumes an exalted station among the branches of human knowledge. Every community that aspires to become intelligent and virtuous should cherish it. Institutions for the promotion and diffusion of useful information should have special reference to it. And all people should be induced to look back to the days of their forefathers, to be warned by their errors, instructed by their wisdom, and stimulated in the career of improvement by the example of their virtues.

The historian would find a great amount and variety of materials in the annals of this old town,—greater, perhaps, than in any other of its grade in the country. But there is one chapter in our history of pre-eminent interest and importance. The witchcraft delusion of 1692 has attracted universal attention since the date of its occurrence, and will, in all coming ages, render the name of Salem notable throughout the world. Wherever the place we live in is mentioned, this memorable transaction will be found associated with it; and those who know nothing else of our history or our character will be sure to know, and tauntingly to inform us that they know, that we hanged the witches.

It is surely incumbent upon us to possess ourselves of correct and just views of a transaction thus indissolubly connected with the reputation of our home, with the memory of our fathers, and, of course, with the most precious part of the inheritance of our chil[i.5]dren. I am apprehensive that the community is very superficially acquainted with this transaction. All have heard of the Salem witchcraft; hardly any are aware of the real character of that event. Its mention creates a smile of astonishment, and perhaps a sneer of contempt, or, it may be, a thrill of horror for the innocent who suffered; but there is reason to fear, that it fails to suggest those reflections, and impart that salutary instruction, without which the design of Providence in permitting it to take place cannot be accomplished. There are, indeed, few passages in the history of any people to be compared with it in all that constitutes the pitiable and tragical, the mysterious and awful. The student of human nature will contemplate in its scenes one of the most remarkable developments which that nature ever assumed; while the moralist, the statesman, and the Christian philosopher will severally find that it opens widely before them a field fruitful in instruction.

Our ancestors have been visited with unmeasured reproach for their conduct on the occasion. Sad, indeed, was the delusion that came over them, and shocking the extent to which their bewildered imaginations and excited passions hurried and drove them on. Still, however, many considerations deserve to be well weighed before sentence is passed upon them. And while I hope to give evidence of a readiness to have every thing appear in its own just light, and to expose to view the very darkest features of the transaction, I am confident of being able to bring forward[i.6] such facts and reflections as will satisfy you that no reproach ought to be attached to them, in consequence of this affair, which does not belong, at least equally, to all other nations, and to the greatest and best men of their times and of previous ages; and, in short, that the final predominating sentiment their conduct should awaken is not so much that of anger and indignation as of pity and compassion.